The New York Times

December 4, 2009

The Lower East Side, Home to the Young and Emerging

By Ken Johnson

The Lower East Side is not the new Chelsea and probably never will be. The exhibition spaces are comparatively small, and except for Lehmann Maupin, there are no big-box commercial vendors showing internationally acclaimed talents. Furthermore, the neighborhood is crisscrossed by busy thoroughfares, and the galleries are widely dispersed among all kinds of nonart businesses. There are lots of bars, restaurants and boutiques, and many galleries are open on Sunday, unlike those in other parts of Manhattan. But while this can make gallery hopping fun for casual visitors, the geography can make it a chore for those mainly looking for art.

The gallery scene here is more sober than that of the East Village of the 1980s, and not as hip as Williamsburg was in the '90s. It is a little like what SoHo was B.C. (Before Chelsea).

The Lower East Side has the gleaming, new New Museum at the north end, and, at the other, Reena Spaulings, a deliberately scruffy place on the edge of Chinatown that specializes in obscure and defiant forms of Conceptualism. (It is between shows now.) Galleries falling in between exhibit mostly young and emerging artists, which means that you see much that is only marginally better than graduate student work. But you can also discover exciting artists you've never heard of before. So no serious art follower can afford to overlook the Lower East Side. My own recent tour of the neighborhood's galleries did not turn up anything likely to rock the art world, but it was not a bust either.

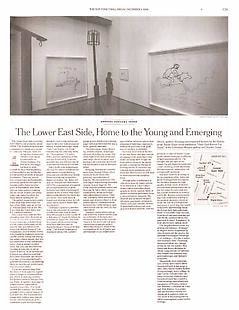

If you are approaching from the west or from uptown, a good place to begin is Lehmann Maupin, which is showing work by the British celebrity bad girl Tracey Emin. In spidery drawings of naked women captioned by scrawled texts like "You made me feel like nothing," Ms. Emin grapples with a messy history of love and sex. She translates her image-text combos into various forms: small monotype prints; embroidery stitched into beige blankets; and a stop-action animated video of a woman masturbating. A white neon sign reads: "Only God Knows I'm Good." Considering her affecting memoir, "Strangeland" (Sceptre, 2006), and the slightness of her current visual work, it seems possible that she will one day be remembered mainly as a writer.

Mary Kelly, who helped pave the way for today's rebellious female artists, is included in a three-person exhibition at Simon Preston revolving around the theme of residue. Ms. Kelly, creator of "Postpartum Document" (1973-79), a monument of feminist art, is represented by a piece from the late 1990s consisting of clothes-dryer screens with vinyl letters embedded in the thick layers of lint. They spell lines of found text relating to war in Lebanon. Jenny Holzer meets Martha Stewart.

Christian Capurro's contribution is the byproduct of a project in which he paid each of more than 260 people to erase a page of a 1986 issue of Vogue Hommes International magazine. This took five years, which seems a long time for a Marxist spin on Rauschenberg's "Erased de Kooning." The erased magazine is displayed along with a photograph of it in which every double-page view has been layered into a thick, ghostly laminate.

The third artist, Klaus Mosettig, creates elegant, seemingly abstract drawings by projecting white light from slide projectors onto large sheets of paper and tracing with a fine pen and black ink the shadows cast by dust particles.

Bringing feminist art smartly up to date, Rachel Uffner offers works by Barb Choit, who presents reproductions of kitschy, '80s-era posters by Patrick Nagel representing beautiful women in sexy lingerie. Ms. Choit buys the posters online and then partly fades them, using a tanning bed, lamps and other skin-darkening products. Then she translates them into ink-jet prints and attaches them to clear plastic panels, creating tension between the risible imagery and slick format and her own sly conceptualism.

Another young artist with social concerns, Juanli Carrión, has an exhibition of his light-box-mounted, photographic transparencies in the downstairs project room of the nonprofit gallery White Box Projects. Each of his extraordinarily lucid landscape photographs is an antipicturesque collision between nature and abandoned buildings, highways, billboards and other junk products of modern civilization.

Secreted in several of the boxes are machines that play sounds of singing birds, and others that make scrolling lines of light behind watery areas in the photographs, creating the illusion of moving waves. It's hard to say whether these gimmicky additions are unnecessary or will lead to more interesting complications.

Photographic truthfulness is still a live issue for many artists. Erin Shirreff (at Lisa Cooley) makes black-and-white photographs in which random blobs of plaster resemble specimens from a natural history museum. Ms. Shirreff also produces elegant, off-white, geometric sculptures, whose curiously smooth, blotchily patterned surfaces are composed of plaster and ash. And she presents a video of Roden Crater under slowly changing conditions of light and atmosphere. The thought that the light artist James Turrell might be inside the crater, working on his interminable construction, makes this video especially amusing.

You don't have to be young to be an emerging artist. Some languish in purgatorial emergence for decades, despite the high quality of their work. Erik Hanson has been toiling under the radar for some 20 years and now has a good exhibition at Sunday L.E.S. Mr. Hanson creates paintings and sculptures relating to his musical interests, which include the Velvet Underground and disco. A set of Pop-Surrealist sculptures representing white birch logs have butt-ends fashioned to resemble vinyl records. A series of canvases bearing spirals thickly painted Alfred Jensen-style is titled "Eurodisco." It is an infectiously upbeat show.

The neighborhood's most surprising exhibition is "Frottage" at Miguel Abreu. Organized by Alex Kitnick and devoted to the outmoded technique of frottage — or rubbing — it is like a miniature museum show. Providing historical ballast are vintage works by the Surrealists Max Ernst and Henri Michaux in which compositions of rudimentary shapes and textures suggest landscapes and fantastic creatures.

Meanwhile, four contemporary artists and a team called Scorched Earth bring us up to date. John Kelsey makes Bubble Wrap rubbings, and a collage by Sam Lewitt includes fake rubbings of ancient Chinese coins. Scorched Earth has created a Cubist frottage and added fake signatures of Picasso, Jacqueline Kennedy, Leonardo da Vinci and Walt Disney. It is jejune, and the overdone vitrine it is displayed in makes it more so. The show is interesting but unlikely to precipitate a new fad for frottage.