Emin-ence Gris: Tracey Emin Comes to America

By Dan Duray

A few weeks ago, Tracey Emin crossed her motorcycle boots and leaned forward in her chair between two Doric columns at the New York Academy of Art in Tribeca, bracing herself, it seemed, so that she was better positioned to launch stories from lips that are always somewhere between a pout and a snarl.

To be honest, she said, her London dealer Jay Jopling, founder of the White Cube gallery, didn’t even know she was an artist when he first took her on in 1993. He knew she worked with Sarah Lucas and thought she was “a kooky outsized person,” so he took her up on her offer, made at a dinner, to “invest in her creative potential” for £10.

After relating this story, she teased her New York dealer David Maupin—of Lehmann Maupin, where her two-gallery show of new works opened last month, part of a protracted one-woman British invasion that includes her first museum show in the States, at MOCA North Miami this December, and her purchase of an apartment there—by pointing out his late arrival to everyone in the room (at this, the suited dealer gave a little wave and sat down).

Soon she was on the topic of her best-known piece, My Bed (1998), which is just that, transported, bodily fluids and all, to a museum. “People always say, ‘It wasn’t really that dirty, was it?’” she said. “And I say, ‘No it was much worse.’ I’ve edited it. I’ve taken things away.”

There was no stage, so Ms. Emin sat on the same level as the 30 or so assembled students, and there was little to protect them from her reaction to the first audience question.

“William Kentridge,” began the nebbishy young woman who asked it, “describes artists as ‘pain vampires,’ who need a lot of trauma for their artwork. I was wondering if, in some ways, you create these really intense experiences for yourself to have a place to make art from?”

“Of course not!” Ms. Emin said, talking with her hands. “Basically, what you just said is that I’ve really fucked myself over—”

“No!” cried the questioner.

“—so that I could make a painting for an exhibition,” Ms. Emin continued. “That would be so pathetic. I’d much rather have a good life and a clear conscience. It’s not that way ’round.” Good artists, she said, her eyes never leaving the questioner, work only with what life has given them. “When I taught a lot in the ’90s in art schools and there were a lot of little imitations of me, it would drive me mad! These girls who had experienced fuck-all in their lives, nothing, were creating these bizarre little scenarios to make themselves think that they were angst-ridden, to make some angst-ridden work. When actually it would be far better for them if they’d been painting little still lifes of roses. It would have been a lot more honest and a lot more beautiful.”

“So I take umbrage by what you said,” she finished, after another minute of this. “It’s actually quite an offensive thing to say to somebody, anybody.”

“I deeply apologize,” said the questioner. It was a while before anyone else asked a question.

If Americans are going to see much more of Ms. Emin in the near future, they would do well to remember that the tenderness in her work has been sharpened by pain. If the Kentridge fan had read any of Ms. Emin’s too-weird-to-be-fake weekly columns for The Independent, it would have been quite clear to her that what the artist does is no kind of shtick.

“I have never, never, ever, ever known any man to be faithful to me,” she wrote in one. “Have you ever found someone you love in bed with someone else? God it’s a killer. What I did was sit by the side of the bed and tell them how weak they were, and chain-smoked their cigarettes, and left them in a puff of smoke.”

“People want to come up to me on the street and hug me because they think I’m lovely, but I’m not,” she said, perhaps a little unnecessarily, later in the talk. “I’m quite a brittle person, actually. I don’t like being touched.” Because she’s made art related to her two abortions, women often want to discuss their own with her, despite the fact that she may be literally the worst person in the world to do that with.

“I had two abortions, but made some art over it and I got over it,” she said, speaking to an invisible fan. “I moved on. You have to move on. I’m not going to give you a hug and tell you everything’s going to be all right.”

Just what is it that makes today’s Tracey Emin so different, so appealing? Over breakfast at The Standard a week after the talk, she said that she’s come to terms with such flattery on the street, and with her young imitators, “the mini Traceys,” who are growing ever younger now that she’s taught in high schools in England. “It’s actually kind of healthy at that age, I think, to be working with a diary and doing this, doing that,” she said. “And I’m a much healthier influence, say, than Sylvia Plath. I am alive.”

Not that she has a choice about it, given her ubiquity in the U.K. She’s covered in the tabloids (The Sun recently ran her review of David Bowie’s new album), and last summer she carried the Olympic torch in her hometown of Margate, a seaside town that she described as “a cross between Coney Island and Santa Cruz.” If her American geographical references might need finessing, she’s pleased at the idea that she might soon be as big here as she is across the pond. “It’s almost like I’m 35 and my career’s just taking off or something,” she said.

Her show spread across the two Lehmann Maupin spaces. In Chelsea, there’s a long table surrounded by sentimental drawings of a couple having sex. The table holds several bronze statues with a white patina that makes them look slightly like the products of an elementary school art class. They’re plinthy, with a large box making up most of each statue. On top sit little human and animal figures. One has a single swan and the word “HUMILIATED” carved into the base, it seems, with a toothpick. “I WHISPERED TO MY PAST DO I HAVE ANOTHER CHOICE,” reads another, below a nude woman riding an elk.

Most YBAs can be too slick for their own good, but Ms. Emin has never shied away from emotion. In her talk, she attributed this to the fact that most of them went to the more theoretically minded Goldsmiths College, whereas Ms. Emin received her M.A. from the more conservative Royal Academy of Art.

“I was a roaring expressionist,” she said during her talk, and then went on to use an analogy that was, all the same, a little YBA in its capitalism. “My favorite artist is Edvard Munch, who has been wholly unfashionable for the last 20 or 30 years. And now Munch has risen to be the highest-selling painting of all time, The Scream. So I’m back, I’m back on track. I’m on the right side of it. I was just out of fashion for about 20 years, and now I’m back in vogue again.”

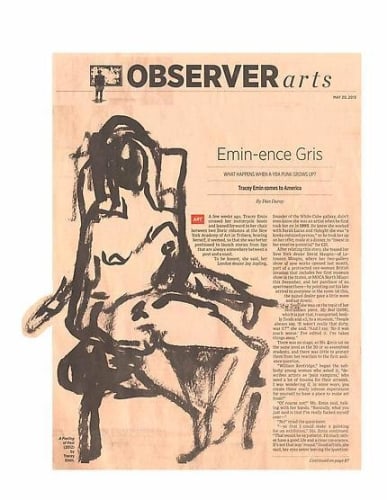

As with much of her work, each of the Lehmann Maupin statues is only part of the story. Chapter 27, say, of a novel, with no other context. The works at the Chrystie Street space are all drawings, inky nude self-portraits of Ms. Emin sitting in a chair. With these, the story is a little clearer. They’re based on her perception of herself while she’s at her remote home in France, where she thinks and works alone, and rarely wears clothing.

“I’m thinking what I look like in my house in France,” Ms. Emin said, “but first off, what I look like, how I feel sitting in this chair from the kitchen, then from just slightly outside it, beside the ceiling. Then from outside the house looking down, then from way up in the stars, like into infinity, looking down at me, and God I’m tiny. And I’m really lonely. That’s what I look like.”

With the exception of her CBE (“It means that in a time of crisis in the civil world, I could give orders—I’m considered a leader”) she seems not to have enjoyed aging. Every reinstallation of My Bed is an assault of memory. It now comes with little plastic bags for the things that will be added to it, like the evidence bags on CSI (her joke). She no longer smokes, and the cigarette butts would be in middle school, if they were people. Period blood? She’s post-menopausal. Condoms? Hasn’t had sex in years.

“The celibacy works really well with all the work I’ve been doing,” she added, speaking of her nude chairs. “I’ve been celibate for—” she then seemed to grow diplomatic as she explained that her friends always liken her definition of sex to Bill Clinton’s. The dipolomacy was short-lived.

“My idea of sex is like hardcore, active penetration,” she said, “so if I haven’t ‘had sex’ for three or four years, it’s because I haven’t had hardcore penetration. I might have had some sexual acts, but actually what I haven’t done for a long time now is just that, and I’m not necessarily interested in it. It’s hard to explain. I need to feel really, really, really in love and trust someone. I don’t just want gratuitous sex.”

So the drawings are a celebration of self-reliance as much as they are a catalog of loneliness. Appropriately, there seemed to be very few couples at a book signing at the Chrystie Street space later in the week, but upstairs, Ryan Jordan, 33, and a female friend stalked some of the lonely chair drawings together. Mr. Jordan, who is British, is a big fan of Ms. Emin’s. He’d never met her before but was pleased that she’ll be spending more time here, and hopes she’ll fit in.

“British people are pretty brash and honest and open, at least her and I are,” he said, “and outspoken. And you know, Americans are very P.C. and hug everything out. She’s more emotional and out there. So I don’t know how Americans will take to that.”

Did he have a favorite Emin piece?

“Yes,” he said. “It’s not here, but it’s a neon heart, and inside it says, ‘You forgot to kiss my soul.’ I actually have it tattooed on my chest.”

He whipped out his iPhone, on which he had a picture. He’d meant to show it to Ms. Emin when he had his book signed, but he’d chickened out. His female friend, an American, encouraged him to go back and do so. What artist wouldn’t be flattered by such a gesture?

Downstairs, I happened to catch the pair walking away from the book-signing table. Mr. Jordan looked a little shell-shocked. Had it not gone well?

“I’m disappointed,” he said.

“She said,” his female companion reported, “that she had had two friends in the past ask her to do tattoos for her, and she did, but then they both died. So she said it was a bad omen.”

“It couldn’t have gone worse, actually,” Mr. Jordan said.