Through the Grid

Rather than step off the grid, some artists look through the grid and embrace the illusory qualities of transparent fabrics.

By Lois Martin

Gauzy fabrics of simple open plain weave – like voile, cheesecloth, chiffon, and organdy – are primary woven structures so familiar that we ten to overlook their evocative qualities. But while the crisscrossing warps and wefts of these fabrics define a two-dimensional plane (as all weavings do), in these, the interstices between threads play tricks with light, just as they do with theatrical scrim, window screens, and veils. All these appear when strongly front-lit and disappear when backlit. When stage lights flood the front of a painted theatrical scrim and the stage is dark behind it, the scrim shows as a solid backdrop. When stage lights go on behind it, the scrim melts away, revealing the scene beyond. Likewise, a dark veil masks the wearer's face, but the wearer sees out clearly (because they are looking through the cloth to daylight). Similarly, a viewer standing outside a house in bright sunlight sees the screens in the dark windows. From the same observation point at night, when the lamps go on inside the house, the screens vanish.

Under gentle light, sheer fabrics transform as well. When both sides are lit, a scrim slightly diffuses the scene behind it; when a fabric "veil" is colored, it will tinge what lies behind. All these tricks of light make open weave fabrics illusive, as they balance between light and shadow, solid and air, visible and invisible. This immateriality is further emphasized by their lightness: un-stretched, they tremble with every breeze. No wonder then, that for centuries in the West, crumpled and billowing voile-weight fabrics have been used by artists to represent the spiritual and ineffable: from the vital energy expressed in the streaming robes of Classical Greek marbles to the purity and otherworldliness of angel drapery in European painting.1

Other associations lend poignancy to transparent fabrics. For one thing, their flimsiness contrasts radically to the firmly woven, hardwearing drills and twills of sensible work clothes. "Sheers" are fabrics of summer and evening, and thus symbolic of what is evanescent. Open-weave gauzes are also breathy: think of hospital bandages and cheesecloth - these can cover a chemical process that needs to "breathe" or "sweat," or a wound that needs to heal, without smothering or spoiling. Because they admit oxygen, woven tissues (from Old French, "woven") resemble living tissues or membranes.

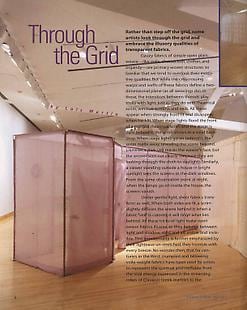

Airiness permeates the architecture that Korean-born artist Do-Ho Suh fashions out of nylon fabric as light as parachute silk. Filled out and suspended by wire armatures, Suh's rooms and roofs and arches - portions of his past dwellings - have the sheen and crisp perfection of a molted chrysalis or sloughed-off snakeskin.

The transubstantiation from tangible solid to ghostly shell is captivating and mimes the way we remember our lives in space. Color seems to hover around Suh's pieces (rather than being directly tied to them), paralleling the way smells and memories pervade once-familiar habitations. Inside, humble objects - electrical switches, toilets, and steam heat radiators - bear timeworn imprints of our bodies. Suh's fabric replications, as in Dream House (2002)2 - like an inversion of the impulse to "bronze the baby's shoes," dissolve these into phantoms. We regard their clear geometry with surprise.

Suh's stripped-down, "X-ray-ed" translations of space exploit cloth's neat grains and mirrored symmetries. Mirroring is redoubled in works like Reflection (2004),3 an arch copied from one in Suh's childhood home in Seoul. Like an arch reflected on the surface of a still pond in a Japanese garden, Suh duplicated a second arch upside-down beneath the first. In another installation, Staircase (2003), he repeats two full-size stairways, one above the other, inviting an impossible climb.

Japanese-born artist Shizuko Kimura uses sheer fabrics to very different ends, drawing figure studies through muslin with a needle and thread. Working from life, Kimura "stitch-sketches" her subjects with immediacy and captures their vitality with a few deft marks.

Mode/s in NY was included in the recent Museum of Art and Design show Pricked: Extreme Embroidery4 and was hung away from the wall, so each thread line sewn through its textile grid read both as a knotted strand and an artist's gesture. These are artist's strokes "caught in a fine net" (rather than impressed into paper). Textile historians agree that weaving is at least 20,000 years old, so the capture and isolation of an artist's thread/marks into such a prehistoric matrix feels a bit like insect wings stuck in amber. Humans have drawn for millennia, though time has erased most ancient sketches as surely as if they'd been written on water. Paleolithic cave paintings do give us a glimpse of what we have lost, and Kimura's lines - sure, sensitive, and strong - hark back to a primordial impulse.

On her "brain maps,"5 Jessica Rankin embroiders text and images onto organdy. She seams sections of organdy together, sometimes in different colors, and then stitches into them. She mounts the large pieces with dissection pins some inches away from the wall; the sheer fabric projects a colored haze behind. Rankin's text, image, scale, and wall-mounting all suggest the oversized atlases and biology charts of a school classroom. But threads and shadows entangle visually, making it hard to parse the letters; the confusion builds because Rankin stitches her texts through the organdy with a continuous strand. At first glance, letters join, and words run together, as if they were written in some super-inflected language of impossibly long words, like Welsh or Quechua. Gradually, they resolve into understandable but open-ended, haiku-like statements.

The thready strangeness of Rankin's letters distracts a viewer from simply trying to dissect their meaning - they seem incorporated into the body of the fabric - and so suggest one of those rumored "secret codes," or subversive women's scripts like woven Nu Shu Chinese ideograms, or the "enemy lists" that women of the French Terror encoded into their knitting (immortalized by Dickens as Madame Defarge).6

Many of the above artists' preoccupations with the thread and fabric spatial dynamics seem pre-figured in works by the late Lenore Tawney (1907-2007), whose interest in the ethereal was life-long, and whose sensitivity to line and thread had been honed not only by weaving, but also by her studies with Archipenko and friendship with artists like the minimalist painter Agnes Martin. Recently published memorials include arresting photos of her from the late 1950s, unreeling strands of threads at loom or warping frame.7 Her New York Times obituary shows her flanked by a diaphanous weaving, Shadow Rive r(1957), so dematerialized as fabric that its eccentric warps and wefts could not hold together: Tawney fused the threads with plastic film, and sandwiched them between sheets of glass.8 This bonding would have muted the fluidity of her threads; other loom-based weavings from the period hang freely.9

Another artist intrigued with ephemeral cloth is Grace O. ("Ronny") Martin, my mother, who taught Weaving and Surface Design at Michigan State University, and who has always drawn inspiration from the natural world around her. In her book, The Quiet Joy: Designing from Nature,10 she encouraged readers to walk in the woods with wide-open eyes, scrutinizing, for example, the "delicate tenement"11 of a bird's nest or filmy network of a spider web, "designed to cushion the eggs, trap the food, keep out enemies, or serve as a communal or nursery tent to protect the young ... constructed without knots ... What weavers! What spinners!"12 She urged: "Very early some morning look outdoors at small weeds and shrubs. The dew condensed on webs destroys their camouflage and makes them easy to find. A few hours later, this evaporates, making them invisible once more."13

Martin herself mimicked the on-again-off-again camouflage of webs in a series of semi-transparent hangings of Swedish linen. Seeking to capture effects like "sunlight coming in a golden shaft through a leafy branch" or "frost patterns on glass" on her loom, she wove "... inlay with shaggy linen threads used as a discontinuous weft, supplementary to the tabby weft."14 The fine, regularly tabby (plain weave) forms a tulle-like foundation, through which the inlay threads meander. When these pieces hang, the subtle tabby disappears - leaving the supplementary wefts hanging midair - with the lovely insubstantiality of a spider's line.

-Lois Martin is an artist and writer. She lives in Brooklyn, New York, and teaches Fashion Design at the Art Institute of New York City.

1 See Anne Hollander, Fabric of Vision: Dress and Drapery in Painting (London: National Gallery Company, 2002).

2 Shown at Lehmann Maupin, 540 West 26th Street, NY, NY 10001, May 30 - July 18, 2003

3 Shown at Lehmann Maupin, 201 Chrystie Street, NY, NY 10002, November 29, 2007 - February 2, 2008.

4 Pricked: Extreme Embroidery, Museum of Arts and Design (MAD), New York, NY; November 8, 2007 - April 27, 2008.

5 Shown at P.S.1 MoMA, Jessica Rankin: The Measure of Every Pause, February 9, 2006 - June 5, 2006.

6 Google "Nu Shu" for references and controversies; Charles Dickens wrote about Mme. Defarge in A Tale of Two Cities (1859).

7 See Kathleen Nugent Mangan, "Remembering Lenore Tawney," NYARTS Magazine (July - August 2008/NOTED); and Sigrid Wortmann Weltge, "Lenore Tawney: Spiritual Revolutionary," American Craft Magazine (February/March 2008).

8 For a structural description, see Mildred Constantine and Jack Lenore Larsen, Beyond Craft: The Art Fabric (New York: Van Nostrand Reinhold Company, 1973), p. 266.

9 Two beautiful examples illustrated in Constantine & Larsen: p.46, Thaw (1958) Collection: Cooper-Hewitt Museum, New York; and p.47, BoundMan (1956), Collection: Museum of Contemporary Crafts (Now MAD:The Museum of Arts and Design).

10 Grace O. Martin, The Quiet ./0)1." Designing from Nature

(New York:The Viking Press, 1977).

11 Martin, p. 75.

12 Martin, p. 85.

13 Martin, p. 100.

14 Martin, p. 122