New York Times – T Magazine

February 24, 2012

Artifacts | Mary Corse

By Linda Yablonsky

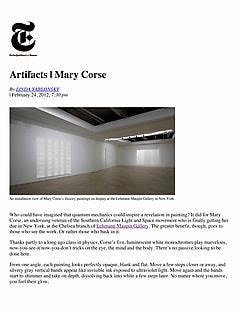

Who could have imagined that quantum mechanics could inspire a revelation in painting? It did for Mary Corse, an undersung veteran of the Southern California Light and Space movement who is finally getting her due in New York, at the Chelsea branch of Lehmann Maupin Gallery. The greater benefit, though, goes to those who see the work. Or rather those who bask in it.

Thanks partly to a long-ago class in physics, Corse’s five, luminescent white monochromes play marvelous, now-you-see-it/now-you-don’t tricks on the eye, the mind and the body. There’s no passive looking to be done here.

From one angle, each painting looks perfectly opaque, blank and flat. Move a few steps closer or away, and silvery gray vertical bands appear like invisible ink exposed to ultraviolet light. Move again and the bands start to shimmer and take on depth, dissolving back into white a few steps later. No matter where you move, you feel their glow.

The illusion derives from tiny glass beads that Corse, now 66, mixes into her paint before brushing it on the canvas. The same microspheres, as she calls them, are what make the white lines on a two-lane blacktop reflective in the dark. “But my paintings are not reflective!” Corse was quick to say during a recent visit to New York from her home in the Malibu hills of Los Angeles. “They create a prism that brings the surface into view. I like that because it brings the viewer into the light as well.”

The idea, she said, is to get inside the paintings — “to create a space that actually isn’t there.”

Perhaps that is why the subtly angled Rem Koolhaas-designed gallery makes the ideal frame for Corse’s paintings. They look much more alive here than they did last fall, when she made her debut in London at the airplane-hangar-size White Cube Bermondsey, where they were hanging in a narrower gallery and their effects were harder to grasp.

At Lehmann Maupin the paintings have either one or two satiny bands. Gazing into one is like watching a cloud move outside a barred window. The show’s central and most transcendent canvas is different. When seen from across the room, the canvas reveals a pair of those hard-edged panels as bookends to stacked bricks of roughened brushwork that creates its own shadows. Move closer, of course, and the texture disappears.

Corse’s minimalist geometries may remind some viewers of Agnes Martin’s penciled grids, but they look different in every context. The first time I saw one was last summer, in the basement of a Venetian palazzo. Illuminated by pin-lights, it softened the dark surrounding stone wall, while its inner bands took on the astrophysical properties of a bright full moon.

Corse has been effecting her magic since the 1960s, when she started out making shaped white or black canvases but also worked in fluorescent light, hiding their generators in the wall, so each piece seemed to hover weightlessly in space.

After 10 years of painting with light, she shifted to the polar opposite and started making large “black earth” paintings with heavy slabs of dark glazed clay. She also took that physics course at the University of Southern California. “I realized then that there was no objective truth,” she said. “So I went back to painting, because it’s inherently more subjective.”

As a younger member of the male-dominated Light and Space group, Corse was virtually ignored by its leading male figures, like the artists Robert Irwin and James Turrell. Though the Guggenheim Museum snapped up one of her large white monochromes in 1970, Corse labored in semi-obscurity for years, raising two children on her own and struggling until she was 40. Nevertheless, she kept on painting. “What else are you gonna do,” she said, “if this is who you are?” It was only last year that she began to get attention beyond the Ace Gallery in Los Angeles, her primary representative over the last 12 years.

Throughout her career, the nature of perception has been Corse’s subject, but it only underscores her basic premise. “There’s nothing static in reality,” she said. “So I didn’t want my paintings to be static either. But we live in an abstract universe and it’s pure abstraction I’m after.”