Kader Attia is a French artist of Algerian descent currently based in Berlin whose practice often investigates historical misunderstandings. His installation The Repair from Occident to Extra-Occidental Cultures, 2012, was a highlight of last year’s Documenta 13. He recently expanded the research he developed for that work into the exhibition “Repair. In Five Acts,” which is on view at KW Institute for Contemporary Art in Berlin through August 25, 2013. Here he discusses the intellectual framework of this project and how it evolved into its current presentation.

I have been exploring what I call reappropriation for many years now. I borrow the term from the French anarchist thinker Pierre-Joseph Proudhon, who proclaimed that “Property is theft!” in the mid-1800s. Another source of inspiration is the Cannibal Manifesto, written by Brazilian poet Oswald de Andrade in 1928, which theorizes that Brazil could only get rid of its European cultural legacy by “cannibalizing” it. The writings of Frantz Fanon, a psychiatrist from Martinique who took part in the Algerian Nationalist Movement, are pivotal as well for their examination of the psychology of the colonized subject and their path to liberation.

I believe that reappropriation is an endless exercise of exchange among cultures, and I have come to the conclusion that there can only be such a process when there has initially been a “dispossession.” For instance, I remember the 2008–2009 exhibition “Picasso and the Masters” at the Grand Palais in Paris, which traced Picasso’s works back to their artistic sources. I was appalled to see that there was not a single African artifact on display. In the West, one has to be conscious of this dispossession of the non-Western world, otherwise the cultural amnesia that currently dominates the Western mind-set will subsist.

When I was in the Democratic Republic of the Congo in the 1990s, I noticed a piece of fabric made by the Kuba peoples, with applications of French-style embroideries that covered holes made by insects—a gesture of repair rather than decoration. Elsewhere, in the holdings of the Smithsonian Institution, I saw a Congolese sculpture whose original shell-shaped eye had been replaced by an ordinary button. Integrating a Western element into an African object is an intentional act that represents the slave’s resistance to the master’s power.

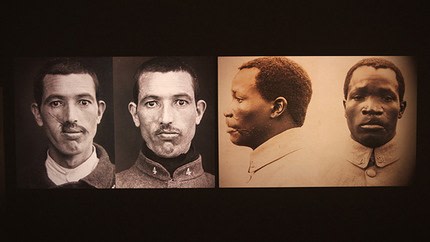

It is through repair that I believe non-Western cultures begin to take back their liberties. For example, in the slide show Open Your Eyes—which I recently presented at MoMA as part of the “Performing Histories” series—I juxtapose photographs of African artifacts that have been repaired with images of wounded soldiers in World War I whose faces were subjected to rudimentary cosmetic surgery. My aim is to reveal that there is a cultural gap between the Western and non-Western worlds through different understandings of the aesthetics of the human body.

In the current exhibition in Berlin, I take my reflection on repair a step further. The exhibition aims to demonstrate how, across both culture and nature, any system of life is rooted in a continuum of repairs. The exhibition is divided into five parts, each devoted to a topic: “Culture,” “Politics,” “Science,” “Nature,” and “Repair in Continuity.” Within “Culture,” for example, there is a video of LP covers, for which the sound track is a musical selection drawn from the records that elucidates how genres such as blues, jazz, salsa, or meringue were developed by the descendants of slaves in North and South America. They were blended with African styles during the post–World War II period of independencies, although Western musicologists claimed that they were being copied rather then returned to their original context.

The key issue behind the exhibition is the debt that European colonial powers owe to the African men who fought on their side, both in Europe and in Africa, during World War I. This moral question is set against current European immigration policies, which intend to close Europe’s borders to the peoples of its former African colonies. The Debt is a slide show featured in the “Politics” section of the exhibition that addresses this theme. The work focuses on the tirailleurs, the soldiers recruited in the French African colonies, and the sans papiers, the so-called illegal immigrants that one could consider the grandsons and granddaughters of the tirailleurs. One of the images included in the work encapsulates its raison d’être. It depicts a tirailleur demonstrating in front of the Palais de la Porte Dorée, which was inaugurated as a museum of the colonies in 1931 and which later became, I would say ironically, a museum of immigration. He holds a sign saying “Our ancestors died for France in 1914–18 and 1939–45. Did they have documentation?”