Billy Childish, as his adopted name suggests, is an antidote to the art world’s pretension. An early punk and expelled from art school, he has always refused to just fit in or comply. He is a prolific musician, poet, writer and painter and this month Lehmann Maupin in Hong Kong exhibits Billy’s recent paintings. Hong Kong seems an odd place to show this determinedly independent artist but China is also the home of the literati artists and poets, some of whom acted much like Billy. He would be at home among them.

Billy Childish: I’m recording tomorrow, so I tried to write some songs last night. I started at 11 and at 11:30 I thought, that’d do, surely. We don’t rehearse. I just trust in the gods.

Chris Moore: Does it ever crash and burn?

BC: Not really—without expectation you can’t have failure. I was not really in the art world until I was fifty, although I had been painting since I was two—quite solidly—and by 12, I was making oil paintings; but [initially] I wasn’t allowed into art schools. Then I did get in to one, and was expelled; then I was on the periphery with music and painting, just carrying on doing it. It’s usually the other way round, burning and smoldering, but I quite like the effect! And when something’s uplifted, it’s as if someone’s knocked on the door—well here’s an example: it’s like a roast pigeon flying into your mouth. That comes from Robert Walser—a great writer.

CM: Fair point.

BC: In music, I’m very irreverent about my work—about most work—and even things that I like are valued for the wrong reason. Take van Gogh—I think he’s overvalued materially and undervalued spiritually. I think van Gogh is much more important than people think he is, and nowhere near as important as people think he is. Van Gogh is so universal because he is so unoriginal.

CM: What do you mean by that?

BC: There’s very little that he adds to any story of painting. He’s highly, highly eclectic; he absorbed everything he admired and because he did that, the universe gets in line and appreciates this strong, ordinary humanity in his work—because he celebrated tradition in everything he did. He emulated friends and colleagues all the time. The universal field likes that and can be quite generous in its gifts back. Van Gogh starts by looking at Millet and ends by looking at Millet; he starts by looking at Rembrandt and ends by looking at Rembrandt. Along the way, he looks at Pisarro. If he’s hanging around with Gauguin, then he copies Gauguin. He never, ever tries to hide these influences. Of course, there are other elements that come in, but he adapts what Pissarro does, he adapts what Guaguin did, he adapts what Millet did. He appropriates with vim, vigor and integrity. He honors the tradition.

CM: But that’s not the reason his works receive ridiculous prices at auction; it’s because of what he represents: an artist who is presenting something “authentic.”

BC: It’s so difficult to take apart these things once they become commodities, and obviously van Gogh’s work has become a banking commodity; but that has very little to do with what van Gogh’s work is about and is nothing to do with its value. Things are valuable because enough people decide things are valuable—it’s just marketing.

CM: There’s a certain sense of anachronism in the paintings; the same could also be said of your music.

BC: I come from a tradition; I also don’t try to hide my hand or try to be very obtuse. My painting is actually not like van Gogh’s. I’m probably closer to the later work of Munch, which has a real looseness to it.

With the groups I’ve played in 20, 30 years ago, some people realized it sounded like Beat Music, but only if you had Punk Rock to inform you about Beat Music. Of course, when you get to the present, our music sounds timeless because it wasn’t of its time. Not being of your time is a very important thing. Norman Rosenthal was at the Royal Academy and he put on the Sensation exhibition there, and he asked me who I thought were my contemporaries. I said “Dostoyevsky and van Gogh.” And he said “Well they’re dead, they’re not contemporary.” My retort was that there’s nothing as dated as the contemporary. When you have something that reflects who you are, it doesn’t have vision; what it has is fashion, and fashion dates very, very poorly. People often talk about how contemporary art’s a success if it reflects who we are in a material, low way. Some people need that. Whereas I try to reflect who we really are—transcendent, spiritual beings which are not fixed in time at all. This again is about authenticity. That understanding of ourselves comes about through our engagement with our time and our material world. I consider myself “super contemporary” but—without trying to sound too up myself—that takes a little bit more imagination and insight to see that invisible aspect of ourselves. Great art is essentially timeless. The fact that people want to put it into a time frame is fine, but the actual resonance of it has nothing to do with the time it is made in. Art hasn’t got any better than the art that was made in the caves, but that doesn’t stop anyone doing it—it remains relevant, this very strange joining with the creator, picking up a burnt stick and joining in with creation.

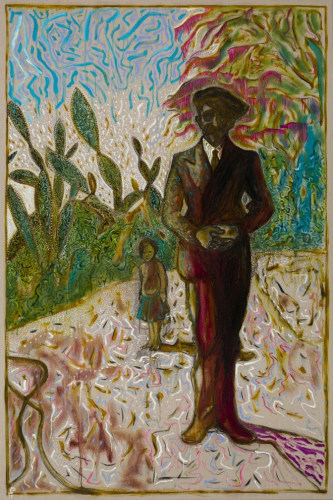

CM: I’ve been looking at the paintings from your show at neugerriemschneider last year, and the ones at Lehmann Maupin. There are three sorts of images that keep arising. Firstly, the forest—and I’m thinking here of Munch or, going in the other direction, Anselm Kiefer’s forests—then mountains, and finally you, like the one with the cactus, which reminds me of Rousseau’s self-portrait.

BC: Who?

CM: Rousseau.

BC: Hang on, I’ve got my computer in front of me now. How do you spell that?

CM: R-O-U-S-S-E-A-U. Rousseau.

BC: I was doing an exhibition in Los Angeles, and there were some cacti in the garden; there’s a photograph my pal took of me and my daughter. I borrow and use anything from anywhere—I’m always looking for an idea, and I thought, “I could do that!” Everything, for me, is like a game, so if I’d seen Rousseau and seen that it was a great idea, then I’d have borrowed it. But these worlds meet all the time. I’m forever reinventing the wheel. [Meanwhile Billy is browsing Rousseau images on the Internet]. Oh! Is it the self-portrait with a palette?

CM: Yes, exactly.

BC: It’s got a bit of that, but his is sooo different from what I do.

CM: I just meant the pose.

BC: Yeah, well maybe we’re both just posers! I’m nothing if I’m not a poser.

CM: But this particular way you present yourself, with a 19th-century moustache, the hats, the clothes—it conjures up other times as well? It’s you—you’re not pretending, it’s you.

BC: Well, I come from a strange family. My father dressed in an Edwardian manner when I was a kid; apparently my great uncle was a dandy. They were farmers and shepherd-type people.

CM: Hard to be a dandy when you’re a shepherd.

BC: Actually, apparently there’s a big tradition of shepherds being very outlandish because they spend too much time on their own. When I was a kid, I always dressed the way I wanted to. I was always out of synch with fashion. The only time I’ve ever been in synch with fashion was when I was a punk rocker in ’77, apart from, of course, that there were no other punk rockers in Chatham. I used to collect militaria when I was a young boy, and we were brought up listening to things about the First and Second World Wars and playing games about them. Now, I always do what I fancy. I did some self-portraits of myself when I was about 13 or 14—I had something going on about the Royal Flying Corps—and I used to make fake moustaches and wear them into town. I went into a theatrical shop and bought fake hair and made waxed moustaches, and I’d wear them about town, and also a scarlet Victorian jacket of the Royal West Kent Regiment that I’d bought with my pocket money. I used to come in for a lot of flak for being like this. But I never stopped. I don’t even like people to notice me or think I look odd, which is the strange thing, so I said to my wife, “Do I look a bit mental?” and she laughed. If I see myself in a shop window, for instance, sometimes I can’t believe what I’m looking at. I follow my whim. That’s what I’ve always done. We have a so-called construct of persona—of course everyone does [have a construct]—but it’s naturally what I’m like. I don’t edit myself.

In England at the moment there are lots of people who dress like me, which is slightly irritating, for example in Shoreditch in London. There are all these people who dress like Billy Childish, which is quite irritating.

CM: You mean the Steampunk aesthetic?

BC: Yes, and I find that people doing that kind of thing puts me off, really, but I refuse to be wrong-footed because I know that they’ll go away.

CM: I’ve been looking at a lot of your paintings and there always seems to be a winter chill in them, whether it’s one of mountains, or there the one with a volcano and clouds coming across it that reminds me of New Zealand; and there are these ones with forest images.

BC: I’ve always had a thing about trees. I’ve always liked Winnie the Pooh and the Hundred Acre Forest, and one of the first books I read was Lord of the Rings, when I was 14—I’m dyslexic—and I managed to get a handle on this reading thing and thought I’d read Lord of the Rings. I like forest spirits and that sort of thing. I look at an oak leaf or an acorn and I’m totally fascinated by them—the same as camouflage, like humans copying camouflage. I like colors and the shapes of things—but I don’t like them in isolation, but in a unity, in a story. I don’t do reductionism. My favorite thing in all my paintings is the abstract, but I like the abstract to be within the whole, figuratively explained.

CM: This brings me closer to what I was getting at about van Gogh in your paintings. Even though you’re using paint, there’s a lot of drawing going on your paintings.

BC: With decent art—here’s a big, bold statement to annoy people!—you have to practice and make the drawing very, very important, and then paint as if it’s not important at all! I think drawing’s great when it’s got this sort discipline. In the 1990s, I was accused of not being able to draw or paint because I didn’t bother drawing. I didn’t show any of my innate abilities because the paintings didn’t require it or ask me to do it. Now, I’m in the middle of a period when the paintings require me to draw and work on them. Sometimes, they want me to put dots on them and do all sorts of things. The painting is quite in charge.

CM: For instance, I like Lucien Freud’s drawings and etchings, but I don’t like his paintings.

BC: Well, Lucien Freud’s a mental case. It’s fascinating. It’s quite incredible what a human can do when it’s tied itself to a chair for life. It’s quite impressive. But impressive doesn’t float my boat. I have very little interest in English art at all. I like Norman Wilkinson, who was an illustrator who made railway posters. With a few exceptions, like in writing with George Orwell, the English don’t really do art. Francis Bacon—some of the early works when he had a little freedom were okay. Later, his work looks like a bath towel with “Life is shit and then you die” written on it, and then you think that has some truth in it but it isn’t the truth. Bacon focuses on nightmarish experience of what life can be like. Being an alcoholic myself and coming from a family of alcoholics, I recognize that world quite well. It’s not one that overly interests me. I don’t find it cool and alluring but dull and constraining. There’s no celebration there. Look at van Gogh and the life that man was leading and the troubles he was going through. But he had incredible generosity and relationship with his creation. And you think, “Well, that’s a victory.” No wonder “Sunflowers” is so popular that it can go on a calendar! Van Gogh wanted that picture reproduced and put in the sailing ships in the Baltic Sea just to cheer the sailors up. That’s just generosity—not the mealy-mouthed approach that a lot of Modernism has embraced as a total truth. It’s not the total truth, just one measly aspect of it. Read Dostoyevsky!—Massive scale and God’s in there all the time. It’s not like some cool Martin Amis assessment of life. They’re like teenagers. There are no adults out there anymore.

CM: So why do forests, mountains and the sea, these elemental things, why do they keep appearing in your work?

BC: I don’t know why they keep appearing in my work. I live on the river. My grandfather was an able seaman in the Royal Navy and the other side of my family was Royal Navy—but I get seasick.

The first mountains started appearing in my work when I met my wife, in Seattle, where we [the band] were playing. There a quite a lot of mountains there, including Mount Rainier [a snow-crested former volcano], which we would go to. So I did a picture of our marriage with Mount Rainier. Its real name is Tahoma, which means “the mountain which is God.”

The reason the forests turned up in those new paintings is that I had some old camouflage jacket and I wanted a friend to take a photograph of me in the trees, because I love oak trees, and in the back of my mind I thought there might be a painting in this.

CM: “Edge of the Forest.”

BC: It’s like a love affair between myself and the world. That’s what my life is: a love affair with my family and the world and the paintings and the world. I’m in love with my wife and with my children, and they are the things that surround me, so they are the things that I celebrate. That’s how God made me. I can write a bit, maybe, and play music a bit—but really what I’m good at is making pictures. So it’s my duty to do that.

Image: Billy Childish, amongst cactus, 2013. Oil and charcoal on linen, 108.07 x 72.05 inches (274.5 x 183 cm)