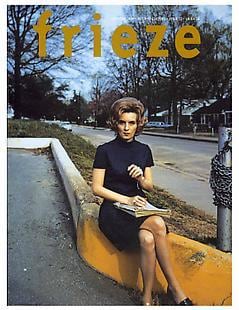

Frieze Magazine

May 2000

Minute Man

By Martin Pesch

translated by Dominic Eichler

Nothing is forever. Everything fades away, decays or will be destroyed. The leftover fragments dream the dream of eternal existence that descends through the ages and awakens feverish minds to eternal truth. Johann Joachim Winckelmann was one such scholar who, in the face of 18th-century Germany's particularism and its flourishing petty bourgeoisie, sought greatness in ancient Greece. Full of reverence, Winckelmann gazed longingly at a block of stone touched long ago by Appolonius' chisel - the remains of a seated male figure that he took to be a depiction of Hercules. Nothing more than a torso and a thigh are recognisable, yet Winckelmann saw in it not only the ideal of beauty but also the human spirit embodied in material form; elevating itself from the heavy earth to the heights of the gods. About this barely legible sculpture in the Belvedere, Rome, he observed: 'I cannot look upon what little remains of his shoulders without them reminding me of two mountains, upon which the entire weight of the heavenly spheres had rested'. In Winckelmann's mind, the fragment not only became whole again, but carried with it the myth of ancient Greece, connecting him directly to that time. Nowadays nothing can lay claim to such permanence, and nobody views anything as the ultimate fulfilment of an era.

Erwin Wurm is often described as a deconstructor of the concept of 'sculpture' and creator of a new definition of how we conceive it. Winckelmann's reception of the Grecian antique, symptomatic of a particular historical interpretation of 'sculpture', may initially appear directly opposed to Wurm's work. Yet although his sculptures sever many ties to the conventions of the genre, they are nonetheless connected, in different ways, with that tradition and its continuation. This has to do with the fact that Wurm's sculptures are dependent on time. Strictly speaking, in order to view them correctly, one must stand next to them. This is especially true of his 'One Minute Sculptures', a group of works which Wurm has been involved with for some years. The central component of most of these sculptures is a person. This means two different things: that the work requires the presence of an individual; and that the viewer is equally present as a part of the sculpture. The series is so named because, by its very nature, each work can barely exist for much longer than 'one minute' - a very, very short period of time in the history of sculpture.

Some examples: a man lifts himself off the ground with both arms and pushes a chair against the wall with his body while someone places a felt-tip pen vertically on the toe of his shoe; a man balances five long rods between his fingertips and the wall; three oranges are stacked on top of each other on the floor; a man stands on two balls; a woman lies on her back with her legs in the air and balances a teacup on each of her feet; a tomato is placed on the tip of a toilet brush handle; a woman stretches out on a landing and presents her profile with a teapot balanced on her head; someone has three pickles jammed between the toes of each of their feet. None of these tableaux can possibly last long. The fact that people, other than the immediate participants, know about them (the basis of Wurm's subsistence as an artist) becomes an interesting play on the sculptures' built-in time factor. Transience is essential to them; equally essential, however, is the fight against it - beyond any question of art market necessity.

The pieces are documented in videos, each of which shows the preparation, rehearsals - including all the unsuccessful attempts - and then, for an instant, the 'completed' work. If one views sculpture as a result of humanity's battle against gravity, then many of Wurm's 'One Minute Sculptures' are you-can-do-this-at-home victories. That they exist only fleetingly hardly diminishes the power of the dream they arise from - the dream to succeed. Along with video, Wurm brings photography into play to record the instance at which his 'One Minute Sculptures' are accomplished. From their moment of sculptural 'becoming', these works appear absurd; their brief instance of possibility becomes an eternity. In the photographs, the surmounting of gravity and the conventions of how people cope with objects, become a rather tormenting document of an uncomfortable and embarrassing situation. You ask yourself: do I really want to see someone with the hook of a clothes hanger in their mouth? Or a man hanging from a partition like an ape? The humour that the sculptures display when shown as videos often disappears in the photos. Suddenly, you become aware of yourself as viewer, and you keep looking even as you realise that you have already crossed the boundary into voyeurism.

The departure point for each sculpture is a drawing, which Wurm executes before each performance. He collects these drawings in a constantly expanding Catalogue Raisonné. In this endeavour, it seems as if Wurm wants to resist the transitory nature of his sculpture: what is documented in the Catalogue Raisonné he considers complete, stored for all time in the archive. If one views the works as insignificant inhabitants of a temporal void, then it seems that Wurm is attempting to compensate with physical plenitude, packing this emptiness with various forms of documentation. By filling storage space and rows of shelves, Wurm gives his work an ironic twist that questions the implications of the 'One Minute Sculptures', and, at the same time, takes the desire for availability, memorability and systematisation to extremes.

The videos and photographs are produced by Wurm, mostly in his Vienna studio, and thus, like Winckelmann's Belvedere fragment, retain a touch of the artist's hand. But just as each moment of a 'One Minute Sculpture' can be represented in various media, the sculptures can potentially be created in many different instances, anywhere, by anybody and - above all - in the absence of the artist. His drawings serve like instruction manuals and occasionally have attached commentaries. Accompanying one sculpture, which involves sitting on the floor with your legs stretched straight out, is the instruction: 'Hold your breath and think of Spinoza'. At exhibition openings, Wurm allows the audience to enact his sculptures on pedestals while viewing his drawings. Likewise, last year, he had students in Liverpool realise certain sculptures with only his drawings as a guide - he was not present. At the opposite extreme is Adelphi Sculptures (1999) - a video in which Wurm appears. Made one afternoon at the Hotel Adelphi, Liverpool, the seclusion and privacy of the room, and the presence of the artist as executor of the piece, gives the impression that he wished - at least for this afternoon - to feel at home and to get on good terms again with his own work.

It still seems to surprise Wurm that one of his 'One Minute Sculptures' was recently used by a fashion photographer as a quirky idea for a shoot. 2 Or that another piece - a woman lying with outstretched arms on a bed of oranges - found its way into a video-clip for Macy Gray's Do Something. The drawing for this sculpture has the following instructions written in the margin - 'Hold the position for one minute and do not think'. Wurm's 'One Minute Sculptures' have finally become a part of the cultural memory of our age, where they can dream the dream of their eternal ephemerality.