Finding the Intangible in the Thrown-Away

Sarah Handleman

Although little scientific research has been done, many people who watch movies on transatlantic flights experience unexpected bouts of tearfulness, even while watching any number of Bruce Willis blockbusters. Some say that the eyes produce more tears to overcompensate for the dry atmosphere in extreme altitudes. Others blame it on a sudden change in the reception of oxytocin, the love hormone. Whatever the case, there is no definite explanation for the act of high-altitude crying; the cause behind a very basic emotion remains a mystery, and that is what much of Nari Ward's current exhibition explores: the other-worldiness and breadth of everyday experience.

The apt-yet-poetically titled Re-Presence gives heaps of cast-away and found objects a stoic existence in Ward's fabricated contexts. The forgotten black backsides of 133 televisions are stacked from floor to ceiling in the first of the museum's three first-floor galleries. The televisions emerge from the wall in a haphazard grid that is interrupted by 133 dangling power cords. And delicately attached to every black television, like a scarf to a woman's wrist, is one white facial tissue. The work, Airplane Tears, is the result of Ward’s fascination with what happens on a plane ride.

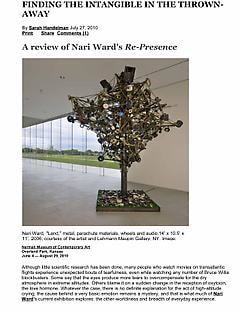

Much of Re-Presence deals with intangible, larger-than-life themes ? religion, poverty, patriotism, and big corporations are present throughout Ward’s work, yet they are portrayed through the use of objects with small, mysterious and personal histories. Not only the television sets and tissues, but also shoelaces, shopping carts, and bouquets are the personal belongings that give Ward’s works their ubiquity.

Ward especially succeeds in his subtle but persistent employment of repetition. In Riot Gate, the black-painted tips of dozens of shoes protrude along the perimeter of a trio of frames that surround three X-ray views of a skull. The triptych is a haunting portrait of oppression and the lengths taken to disguise human vulnerability. The shoes appear again in Palace Liquorsoul, springing up amongst vines of fake flowers that span up the side of a restored neon sign. Both poignant and kitsch, the work is reminiscent of roadside crosses that mark fatal car accidents. More shoe tips emerge in Third World Bank as if representing the silent footprints of poverty and violence. Once a common and valuable currency in Africa, cowrie shells encircle the famous World Bank logo, making a powerful statement of the West's complicated influence on the developing world.

In the third room, the West's global pervasiveness is even more apparent in Glory. Made in 2006 for the Whitney Biennial, the work is a now-timely portrayal of a certain America. Unabashedly patriotic and frighteningly arrogant, the inside of a fully functioning tanning bed encased in metal oil containers has been painted with stars and stripes with the intention of branding anyone who gets in. Compared to the dark realities of Third World Bank and AfroChase (Ward’s reinterpretation of a Chase credit card), Glory is an ultraviolet-infused nightmare of America as company, not country.

Although the New York-based artist’s politics and statements are more obvious in certain works, many of the installations, such as Airplane Tears, remain a mystery. Juxtaposed against themes of Western consumerism, spiritual and otherworldly moments emanate through many works, including The Savior, a video installation that documents Ward’s walk through Brooklyn with angel wings strapped to a shopping cart. Perhaps a nod to Ward's childhood in Jamaica, hints of Voodooism — specifically Obeah — surface as predetermined materials form stirring portraits of dark worlds and ideas. Ward infuses ordinary, found objects with new meaning. Shoes, tar, and shells are the tiny bones of poignant lessons in his unwritten vocabulary of symbolism.

Re-Presence tackles big issues. It is a big exhibition (clearly a massive overhaul of work went into the installation construction), yet Ward punctuates his work with quiet, breathing, haunting humanity. Although the effects of the impoverished world and Gulf oil crisis are not immediately felt in the upper-class bracket of Johnson County, for example, we are all a little vulnerable in a plane up high in the sky.