Elle

July 1995

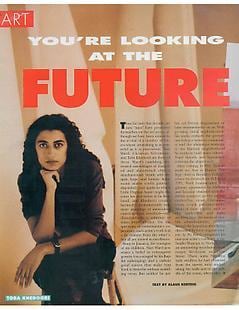

You're Looking at the Future

By Klaus Kertess

Thus far into this decade no new "isms" have presented themselves on the art scene though we have been witness the arrival of a number of loners whose art-making is as powerful as it is precocious. Nari Ward, Christian Schumann and Toba Khedoori are three of them. Ward's rumbling, distressed assemblages of discarded and abandoned objects simultaneously bristle with despair, hope and humor; Schumann makes coolly paint disjointed quilts in which Little Orhpan Annie might discover her real father to be Rimbaud; and Khedoori creates hermetic paintings of meticulous constructions resolved--and dissolved--in a solution of waxy, white silence. On the spectrum of contemporary experience each artist's work is at a far remove from the other's, but all are united in excellence.

Born in Jamaica, the youngest of six children, Nari Ward possesses a belief in redemptive powers (encouraged by his Baptist upbringing) and a radiant good nature that make him hard to describe without sounding corny. But neither he nor his art forces dogmatism or false sentimentality on us. With growing visual sophistication, his works embody the precarious balance between community and the alienation endemic to the Harlem neighborhood he works in (and many others). Ward literally and figuratively redeems the abandoned.

After coming to New York to study art, first at Hunter College, then at Brooklyn College, where he received his M.F.A. in 1991, Ward homesteaded in a gloomy apartment in Harlem and became obsessed with the debris scattered on the streets: umbrellas, dead Christmas trees, crack paraphernalia. Many of these objects, such as the umbrellas and baby strollers, bore the marks of double abandonment, having served the homeless after bring discarded by their original owners. At 30, Ward completed his one-year artist's residency at the Studio Museum in Harlem with an astounding installation in an empty firehouse on 141st Street. There, some 300 baby strollers he had retrieved from the streets were stacked along the walls and in the middle of the room, where they were bound by a flattened fire hose that outlined the contour of a ship's deck. The abandoned suddenly comprised a restive community, a visual chorus that rose to meet the sonorous tones of Mahalia Jackson's "Amazing Grace" playing in the firehouse.

Ward draws his metaphors from his materials' history. His ability to involve and heighten his found objects' bruises and scars while urging them toward beauty adds a new, emotional depth to the irony-clad tradition of assemblage, which has moved from Cubist collages to Robert Rauschenberg's "Combines" and John Chamberlain's crushed-car-parts sculpture.

This past summer, Ward worked on sets for a new dance by Bill T. Jones (in collaboration with jazz musician Max Roach and author Toni Morrison), and he is about to finish an outdoor sculpture in Geneva for the 50th anniversary of the United Nations. It's a bird (of peace) house built from used car mufflers. The house will be turned upside down and have more than 50 pristine white mufflers rising from its base, some with real holes where birds can feed, some with painted holes that give only the illusion of feeding. Urban exhaust and exhaustion hold out hope, and the illustration of hope, in the land of peace and the cuckoo clock.

Christian Schumann's paintings take us on a bumpy road that seems to lead toward a Technicolor adolescent apocalypse. His misspent and misshapen protagonists are the victims, and the victimizers, of our youth culture-Star Trek, Lord of the Flies, The Village of the Damned, cartoons, Bosch, and J. K. Huysmans's fevered synesthesia are 'all part of Schumann's cosmicomics. His paintings are composed of multiple frames similar to those of comic books, but they cannot be read sequentially: they have no continuity and are as dislocated and fragmented as the characters they contain. Advertising logos, printed words, and/or handwritten snippets of tales of woe ("How many more nights of three-for-a-dollar noodle packets?") displace conventional story line and narrative. Schumann has transformed the nonhierarchical, allover composition so critical to American abstract painting into frantically disjointed Psycho-sitcoms. Or are they oracles?

Barely 25 years old, with a perpetually bemused and quizzical look reminiscent of the figures in his work, Schumann has been gathering critical praise since 1992, when a group of his drawings were exhibited in New York, soon after he received his B.F.A. at the San Francisco Art Institute. He has quickly assimilated the lessons of several prior generations of painters, from Carroll Dunham, whose paintings brim with raucous, sexually charged, organic forms, to the late Jean-Michel Basquiat, with his graffiti inspired poetics. Only his deep concern with painting seems capable of cracking his cool.

Schumann's superb drawing changes as effortlessly as a chameleon, depending on the visual and psychological coloration it settles on-from cartoon shorthand to hyper-detailed mimesis. An individual work might combine collage, drawing, and painting alternately deployed in geometric patterning, landscape imagery, mechanical lettering, handwriting, and the startling panoply of physiognomy. The surfaces of his paintings vary from glacial smoothness to worn abrasions; everything hugs the plane of the canvas and hovers precariously between chaos and coherence. Only the eye can hold together these fables that can never be told.

Toba Khedoori's paintings are enigmatic odes to the ambiguities of representation. The artist prefers to let her work speak for itself and says extremely little, in a very quiet voice, but she nevertheless exudes a potent blend of graceful self-containment and steely determination. The quietness has hardly kept her from being noticed. Having just begun to exhibit her work, she is already being heralded on both coasts as one of the most original painters to have surfaced in the 1990s.

Born in 1964 in Sydney, Australia, Khedoori studied at the San Francisco Art Institute and UCLA. Her paintings are made on three large, contiguous sheets of paper, usually measuring about 11 by 20 feet overall. With the paper flat on the floor, she sponges wax across the entire surface, accepting the occasional puddle or stain or shed hairs from her dog. The wax gives the paper more weight and solidity while simultaneously adding a light-suffused, opaque spatiality to it.

After stapling the paper to the wall, Khedoori draws, with the neutrality of architectural drafting, some precisely constructed object or structure (a tunnel, a crane, a building facade, a passenger train, etc.). The perspectival illusion the subject is rendered in is almost always ever so slightly off. Khedoori then paints in the outlines with a tiny brush. The hosting ground embraces the rendered image ambivalently, creating a lyrically shifting rondo of approach and avoidance, illusion and materiality.

The perfectly calibrated scale of the image causes it to become a mirage suspended in a vast space. Slowly the illusion is subverted by its own errors in perspective and by the break in continuity caused by the curling paper. The light created by the wax recedes into a shiny hardness, emphasizing the blunt flatness and weight of the paper. And then the image begins to seek its space and place allover again: illusion's beauty and impossibility arouse and repel each other. Evoking both Gerhard Richter's ongoing investigation of representation and some of the lonely stillness found in Edward Hopper's paintings, Khedoori's work is a poetic analysis of both the nature of illusion and our deep need for it.