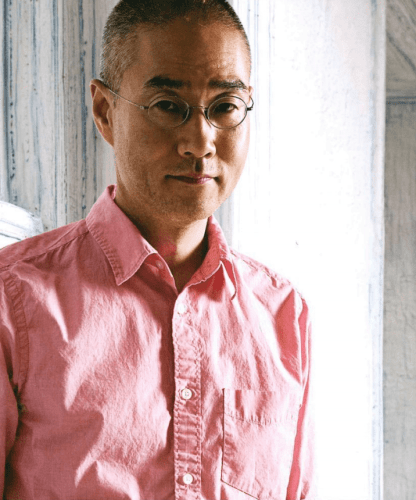

Do Ho Suh is known for his stunning, monumental sculptures and installations exploring issues of identity, history, space, and memory. His works have been collected by such institutions as the Museum of Modern Art in New York, the Tate in London, and the Mori Art Museum in Tokyo, to name a few. Over the last several years, he has worked more and more on themes of home and exploring space and memory, including a to-scale reproduction of his former apartment in Chelsea, first executed in soft sculptures (including all pipes, doorknobs, nuts, bolts, and plumbing fixtures) and more recently in surface-to-surface charcoal and colored pencil rubbings of the same space.

His most recent exhibition with Lehmann Maupin gallery in New York included these new apartment rubbings, recent drawings, and the “Rubbing/Loving Project” he executed for the Gwangju Biennale in 2012. Gwangju was the site of a democratic protect in 1980 that was suppressed by the government and censored by the news media, and scant information on the tragedy is available even today. Suh created to-scale rubbings of the domestic spaces in Gwangju, all of them now empty. In one of the spaces, the company housing for a theater group, he and his assistants entered blindfolded, symbolically re-inscribing the invisibility of this incident in South Korea’s history. Where other projects focused on spaces Suh himself has lived in, with the Gwangju project, he effectively makes monuments to the lives of those who lived through the uprising, and whose stories are still largely unknown.

INGRID DUDEK: You have become quite well known in the last decade for monumental sculptures and installations that touch on the themes of karma and the individual versus the collective. Some of your early works have a military bent. More recently, you’ve been dealing with issues related to home, and I’m wondering if you could talk a little about the evolution of your practice and how these early themes may or may not still be present.

DO HO SUH: I think that the idea that everything started from is my interested in the idea of personal space—emotional personal space—which could be quite broad as a concept. So everything that you just mentioned all falls into that category. The smallest personal space is clothing. So the very early works were uniforms, using the form of clothing as a surrogate to the human body and to address complex human conditions. That also coincided with my time moving to the U.S. from Korea and that all happened all around the same time. The L.A. riot in ’91 also really gave me the chance to think about the identity of the Korean man and how Koreans were perceived by Americans or American media during the riot. That was quite a revolution for me. So everything kind of came together and I started to think about basically everything around me and I started from myself, the smallest unit and gradually it was basically about my surroundings, and I was measuring the spaces that I was not really familiar with without really knowing what I wanted to do.

ID: Your new work also seems more process-drive or even participatory. I am thinking of the video documenting the making of the Gwangju work, showing you and your assistants blindfolded and creating rubbings of the spaces you have selected, spaces that are very humble but very loaded, too. I was wondering if this was something that you thought about consciously.

DHS: Everything started from my apartment in New York. The building is a few hundred years old, so many people lived there and passed through this space and for me, no matter what you do it’s still there. For me it was like my own space; it was probably my most intimate space. For me, especially in the Gwangju pieces, I was expressing my frustration when I was living in Korea when the uprising happened. It was not just my story; it was the people who lived in the community at that time.

ID: What was the experience of doing the rubbings like? Was there any feedback from your assistants on what they went through or felt?

DHS: Well, we were planning on getting it done in three days. It was a fairly small room. That was the hottest day in Korea in history, so it was a really tough situation. We got it all done in one day; it was a really long day. And everybody was exhausted, but I think there was a sense of ritual, the way everything was set. I tried to make it as casual as possible, but once you’re blindfolded and you can’t see, you have to rely on everything on your tactile senses and sound. It was kind of interesting; it was predictable, but when you focus on the project for several hours, it can get quite intense. We had a task. I think that really enhanced our senses more. Including myself, we had six people working in the space, and afterward maybe two or three of them expressed that actually they felt they could see the shapes they were rubbing ever when we were blindfolded. There was some sort of an aura. There was a sense that we had a common experience through the process. It was not a performance piece, but there was a sense of ritual that came from doing things together.

ID: This reminds me of Buddhist monuments and steles that people take rubbings off of. The rubbings are not sacred, but they somehow borrow something of its aura.

DHS: I think maybe over the last five years, it was all about the process and all about the people that I worked with and the space. You have a limited time in this world with a certain number of people. We may have met before in the previous life; maybe this is not the first time being here, because strangely I come back over and over to certain spaces. So definitely there is some meaning that I don’t really know yet, and this is the process to figure it out.

ID: In your works using your old Chelsea apartment, you list the full address of the apartment down to the apartment number. Were there every any repercussions to advertising the address like that, for you or the tenants who have lived there since?

DHS: I never had any incidents like that. It was 2001. Artists are not celebrities! I got a letter from probably an art student, but that was it.

ID: I was interested to learn that you live primarily in London given that your works so often focus on “home” in New York or Seoul. Is your consideration of space and time and experience still retrospective?

DHS: I think having family and kids is something I haven’t done before and that has changed my whole perspective of life. Having kids at my age—they are three and one years old—I’m a very old father and it’s such an interesting experience for me. And so it’s different sets of questions, generally. I’m very slow, I think; I probably have a tendency of regurgitating things over and over again. It’s probably occupational hazard that everywhere I go, I see different spaces, and I’ve started to discover interesting spaces in London because the architecture is quite different. There are more interesting very narrow passages and alleyways. It will come, and I think having a family will come into my work at some point, too.