Making The Trees Dance

New-media artist Jennifer Steinkamp uses very special effects to make "fake nature," boggling the eye and fooling the brain

By Michelle Falkenstein

On a wintry Saturday morning last February, video- and new-media artist Jennifer Steinkamp, wearing jeans, a fleece-lined jacket, and red-framed eyeglasses, rushed into the Lehmann Maupin gallery in New York. It was the last day of her debut at the gallery, featuring her installation "Dervish." The work was named for the priests of the Mevlavi sect of Islam, who spin in religious trances.

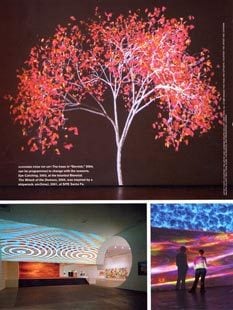

Inside the darkened room, four projected images of trees twirled their branches one way and then back again, their colorful leaves swishing to and fro. The "Dervish" series consists of ten unique trees, all numbered and titled Dervish. As their cycles progress, the trees, the colors of their

leaves and flowers, reflect the change in seasons. The trees appear bewitched, like something out of a fairy tale or a nature lover's fantasy. They rotate in space as their virtual trunks remain firmly attached to the virtual ground.

According to Steinkamp, the trees can be programmed to change seasons on command. "People might feel like they need spring," she says. This change can be triggered by a click on a keyboard, or as she explains, "you can set it up so that it changes when you slam the door."

Then, like Dorothy pulling aside the curtain to reveal the real Wizard of Oz, the artist opens a closet door across from the room, exposing the pile of computers that run the installation.

Steinkamp has consistently shown her art—which began as abstract but has recently turned representational—since the early 1990s, but lately her career has started to pop. "She's one of the most driven artists I've ever met in my entire life," says JoAnne Northrup, a senior curator at the San Jose Museum of Art. Steinkamp, who is based in Los Angeles, is represented by three galleries: Lehmann Maupin, greengrassi in London, and ACME in Los Angeles.

"Jennifer is really entering a new phase," says Northrup, who is planning a Steinkamp midcareer survey for 2006. "Now that she's doing representational work, it's like a sensation." She points to a Steinkamp installation titled Jimmy Carter, named for one of the artist's heroes, as a turning point. The piece, shown in 2002 at ACME gallery, features ceiling-to-floor projected strands of multicolored flowers swaying on three walls, as though in a breeze. The images, which move toward and away from the plane of the wall, are interrupted by the shadow of the viewer. "That was the start," Northrup says. "Then, the trees in Istanbul just blew people away."

The trees in Istanbul were an assemblage of three trees in a Steinkamp piece titled Eye Catching at last fall's eighth Istanbul Biennial, organized by New Museum of Contemporary Art senior curator Dan Cameron. "It looked unbelievable," Cameron says. "For many people, it was the highlight of the whole Biennial. They just saw it and stopped in their tracks." The swaying trees, their branches writhing like snakes, were projected near two ancient Medusa heads on the Yerebatan Cistem.

Steinkamp, a soft-spoken woman with light hair and blue eyes, says that prices for her work range from $25,000 for a "Dervish" tree to $50,000 for larger installations. According to Courtney Plummer, sales director at Lehmann Maupin, "Dervish" was extremely successful. All of the trees—ten plus one artist's print per tree, for a total of 20—were sold to private collectors, foundations, and museums or put on hold by museums. (Those not sold during the gallery show, says Steinkamp, were snapped up at the Armory Show in New York in March.) What buyers got were two DVDs—a signed copy and an exhibition copy—that contained the files for the piece. To run the work, Steinkamp says, collectors need a computer and a projector.

Steinkamp is having a busy year. She is creating projections for a production of Richard Wagner's Tannhauser in collaboration with William Friedkin (director of The Exorcist and The French Connection), which will premiere at the Los Angeles Opera during its 2006—7 season before moving to the Washington National Opera in a subsequent season. She had her second solo exhibition at greengrassi gallery this spring (her first was in 1999), where she showed a piece titled The Wreck of the Dumaru. Next fall she will be part of the Gwangju Biennial in South Korea.

The San Jose Museum of Art acquired one of Steinkamp's abstract pieces, To and Fro, in 2002. Her work can also be found in the permanent collections of the Henry Art Gallery in Seattle, the Corcoran Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C., the Museum of Contemporary Art in Los Angeles, and the Museum of Contemporary Art in North Miami, Florida. In 2001, following an introduction by artist Carter Kustera, the rock group U2 used projections from Steinkamp's 1998 abstract work Sun Porch Cha-Cha-Cha during its "Elevation" tour.

Cameron says it was difficult to imagine that Steinkamp would begin to use representational imagery. "The niche she's carving out is a special one," he says. "For a really long time, her work was abstract, dealing with optical effects. Now she's dealing with technology, projection, and nature. They seem not to have much to do with each other, but the way she uses them, they fuse in a fascinating way."

Despite what might seem like a budding love affair with nature, Steinkamp is about as far from a tree-hugger as you can get. "My sister has a ranch with cows, horses, and pigs, and it smells," she says. "That's why I make fake nature." She recalls visiting her grandparents' farm as a child and staying in the car to avoid the cows. "I remember feeling completely nauseous," she says. "I'm actually not much of a nature girl. You can't get me to go camping."

Steinkamp was born in 1958 in Denver and raised in Edina, Minnesota, near Minneapolis. Edina's claim to fame is that it is the home of the first totally enclosed shopping center in America. "It's cold there, so of course they have malls," Steinkamp says with a smile. Both of her parents are stockbrokers (her mother is retired), and she is the oldest of five children, three girls and two boys.

Steinkamp's mother does not share her daughter's aversion to nature. "She's a flower freak," Steinkamp says. "The news does a helicopter flyby of her backyard every year to see her tulips, and she has thousands."

Steinkamp attended the California Institute of the Arts in Valencia as a motion-graphics major. Then, in 1984, she saw avant-garde computer animation by John Whitney Sr. "Just seeing those things, they looked amazing," she says. "I dropped out of school and started working in special effects." She began working at a graphics-and-animation firm, Robert Abel and Associates in Los Angeles. The following year she moved to New York and spent two years animating television commercials for Fujifilm, Timex watches, and bug spray. "I animated the little cockroaches and the spray can," she says.

Steinkamp moved back to California, and in 1989 she earned a bachelor of fine arts in design and fine art, graduating with honors from the Art Center College of Design in Pasadena. Two years later, she earned a master of fine arts. Steinkamp taught design and media arts at the Art Center College from 1988 to 2000 and began teaching at the University of California, Los Angeles, in 1997, where she still works. She is currently teaching a course called "Time and Motion in Virtual Space" and has taught "Virtual Form" and "Tangible Typography." She lives in a house in Mar Vista, near Santa Monica, with her dog, Cariesta, a Queensland Heeler.

To make her trees, Steinkamp says she starts with the image of a maple, then reworks the bark, leaves, branches, and flowers so it doesn't look like any identifiable tree. Steinkamp says that despite her agility with computers, she was no math whiz as a student. "I fluked out of math," she says. "I didn't understand algebra." According to Northrup, that may be part of why Steinkamp's work succeeds. "So much new-media art is so cerebral," she says. "It's made by an engineer who decided to make art. Jennifer is an artist who decided to be an engineer."

Adds Cameron, "Few artists have taken nature and technology and created a feeling of the uncanny the way she has. We don't see trees as objects that have their very own autonomy and objectives. Jennifer's trees seem a little scary."

Making new-media art is an intense process, with lots of trial and error, says Steinkamp, who likes to work to the sound of electronica, especially to a duo called the Future Sound of London. She has collaborated with musicians on several of her pieces, including Jimmy Johnson, who makes ambient electronica; Grain, a duo that creates a type of electronica called intelligent dance music; and Bryan Brown, a drummer for surf guitarist Dick Dale. In her spare time, Steinkamp practices yoga and lifts weights.

The Wreck of the Dumaru, which was shown at greengrassi this spring, is named for an incident during World War I in which Steinkamp's great-uncle Ernest Hedinger took part. The ship was struck by lightning near Guam, and the 19-year-old Hedinger died after drinking seawater. Then, two members of the crew were cannibalized. Steinkamp created six versions of the piece, two of which were projected at greengrassi. One features a roiling, pinkish red sea under a fractured turquoise sky; the other, a psychedelic sea under a gray-blue sky. (Actually, both the sea and the sky in this piece were made with images of water.)

"Water seems to be a theme for me," Steinkamp says, recalling other works that have the subject of water in their titles, ineluding several from 1995 and 1996 called "Six-Point Sea" and "A Sailor's Life is a Life for Me" of 1998.

Steinkamp cites avant-garde filmmakers Oskar Fischinger, Hollis Frampton, and Jordan Belson as major influences. Other artists who have had a major impact on her work include Eva Hesse, Bruce Nauman, Agnes Martin, Walter De Maria, Bridget Riley, and space-and-light artist James Turrell. "Jeff Koons's basketball piece was very important to me in the '80s," she says.

Architecture plays an important role in her work, and she regularly attends lectures and reads about it. But she explains, "I dematerialize the architecture," creating another space by projecting onto it. For the Tannhauser sets, she will be projecting trees onto structures designed by architect Edwin Chan of Gehry Partners.

"When you see how the work is about painting and architecture as much as anything else, you can see how much she's pushed the medium," says Louis Grachos, director of the Albright-Knox Art Gallery, which recently purchased Dervish 1.

Steinkamp plans to continue to work with images from the natural world. Next, she says, she would like to create a piece about oceans. She's also thinking about making a forest. Yet despite the flowers and the trees and the oceans, Steinkamp still thinks of her work as abstract. "But it's certainly debatable," she adds. "The one rule I stick to is, Everything is simulated. If someone draws or paints, it's simulated, too, but you don't think in those terms."