Working Practice: Tracey Emin at Lehmann Maupin

By Carol Kino

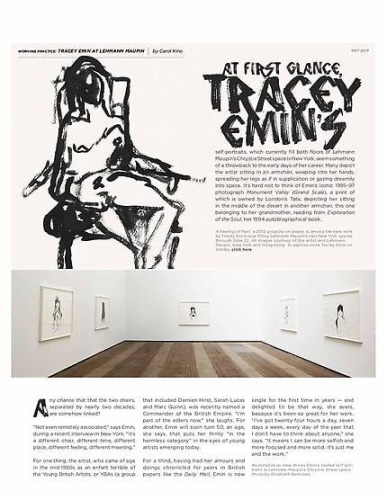

At first glance, Tracey Emin's self-portraits, which currently fill both floors of Lehmann Maupin's Chrystie Street space in NewYork, seem something of a throwback to the early days of her career. Many depict the artist sitting in an armchair, weeping into her hands, spreading her legs as if in supplication or gazing dreamily into space. lt's hard not to think of Emin's iconic l995-97 photograph Monument Valley (Grand Scale), a print of which is owned by London's Tate, depicting her sitting in the middle of the desert in another armchair, this one belonging to her grandmother, reading from Exploration of the Soul, her 1994 autobiographical book.

Any chance that that the two chairs, separated by nearly two decades, are somehow linked?

“Not even remotely associated," says Emin, during a recent interview in New York. "lt's a different chair, different time, different place, different feeling, different meaning.”

For one thing, the artist, who came of age in the mid-1990s as an enfant terrible of the Young British Artists, or YBAs (a group that included Damien Hirst, Sarah Lucas and Marc Quinn), was recently named a Commander of the British Empire. "l'm part of the elders now,” she laughs. For another, Emin will soon turn 50, an age, she says, that puts her firmly "in the harmless category” in the eyes of young artists emerging today.

For a third, having had her amours and doings chronicled for years in British papers like the Daily Mail, Emin is now single for the first time in years - and delighted to be that way, she avers, because it's been so great for her work. "l've got twenty-four hours a day, seven days a week, every day of the year that I don't have to think about anyone," she says. "It means I can be more selfish and more focused and more solid. it's just me and the work."

Some might argue that all Emin’s artwork, chair or no, is linked by self-revelation and a yearning for love. So says Bonnie Clearwater, the director of the Museum of Contemporary Art in North Miami, who will give Emin her first U.S. museum show in December, a retrospective of neon signs. "She is trying to give love a concrete reality in her art, and not at all in a cynical way," says Clearwater. “That is something Tracey has really focused on - not just a love between two people, but a bigger love, and a love of the spiritual as well."

Certainly, love in all its many guises does seem to be the engine that has fueled much of Emin's work. Think of her l998 installation My Bed, littered with condoms and overflowing ashtrays, which marked her U.S. solo debut at Lehmann Maupin and later won her a place on the Turner Prize shortlist. Or the touching Baby Things (2008), seven life-sized bronze simulacra of baby accessories, such as a mitten and a cap, which are installed throughout Folkestone, a seaside town in Kent.

lt is also the underlying theme in the work that Emin currently has on view in Manhattan, where Lehmann Maupin is devoting both of its New York spaces through June 22 to a variety of artworks, all made in the last year.

In the Chrystie Street space are Emin's melancholic “Lonely Chair" gouaches, many of which are also reproduced in a catalog - something of an artist's book - together with new poetry. The Chelsea gallery meanwhile, holds a dazzling yellow neon wall sculpture that reads “l Followed You to the Sun" - also the show's title - and a suite of tiny erotic paintings, rendered in blue-toned acrylic, that bring to mind the erotic drawings of J.M.W. Turner. (They also recall the larger nudes Emin showed last summer in "She Lay Down Deep Beneath the Sea," her hugely popular show at Turner Contemporary, in Margate, the rundown seaside town where she grew up, where they were grouped with erotic drawings by Turner and Rodin.) Also on view is a digital video, Love Never Wanted Me, in which Emin reads a poem about love (or her current lack thereof) over iPhone footage of her latest swain - a wild fox who frequently comes calling at her house in the south of France.

But the focus here is a group of new bronzes, made at the Long Island foundry where Louise Bourgeois once worked. Each depicts a tiny figure - a fox, a swan or a naked woman - poised on a pedestal roughly lettered with slogans like "You have no idea how safe you make me feel." Finished with a shiny ivory patina. their lettering and finger-modeled surfaces suggest they were worked by childlike hands. And, like the baby clothes in Kent, these sculptures totally subvert the monumentality and weightiness traditionally associated with bronze.

Thanks to the Art Production Fund, another bronze, Roman Standard, a new version of a piece made for the city of Liverpool in 2005, has just gone on view in New York's Petrosino Square, a small park in SoHo through September 8. A bird held aloft on a 13-foot pole, it seems to hover near the tops of the trees, as if to suggest that the dove - a symbol of peace and love - has replaced the militant Roman eagle. (This is Emin's second public sculpture in New York this year: throughout February, a group of neon works called "l Promise to Love You” played each night in Times Square.)