Hernan Bas

Where the Boys Aren't

Hernan Bas' paintings owe much to burgeoning nineteenth century questioning of sexuality and sexual identity beyond the enforced male and female dress codes of the day. In an age in which men and women, heterosexual or homosexual, have numerous options as to how they codify and present their sexual or gender identities publicly, the swishy dandies and waifs of nineteenth century literature, painting and illustration stand in stark contrast to the contemporary dominant public faces of sexual minority rights. They seem to be almost a threat to a world in which 'straight acting' has become the epitome of attractiveness to gay men who once stoned police lines in defense of their right to wear dresses and make-up in private bars.

Bas offers us a highly stylised representation based in a masterful understanding of painting that harks back to the seemingly naive explorations of nineteenth century Decadents and bohemians seeking an identity for their various loves that dare not speak their name – absinthe, opium, boys. Looking back at the these representations of men and women involved in 'unnatural' vices and relationships, whether in visual works or literary descriptions from the period, there appears to be a great naiveté; an innocent camp in which the 'feminine' as codified in fabrics, carriage and toilette were appropriated by this new male identity. What would later be understood as lesbian identities are thin on the ground. They would have to wait for the heady years of Weimar Germany to truly forge imagery of their own. The nineteenth century demimondes to which Bas' work refers is very much the domain of the girlish boy: the Ganymede, frequently invoked in the coded literature of the day.

Bas understands implicitly that it was an interesting time, a time of transition that eventually segued into modernism. For one thing, this new identity was not about the things connected with the dandies and rakes that came before.

Bewigged, drenched in cologne and with a penchant for elaborate frothy clothes, certain male ideals of the sixteenth, seventeenth and eighteenth centuries were vastly different from any male ideal purported from the twentieth century onwards. They may have been effete, but they were also, according to all the received narratives, notorious womanisers. Buggering a stable hand, of course, was completely acceptable when drunk or merely in the mood. After all, it in no way represented any meaningful opposition to the way in which such rakes would progress to marry well and sire many children.

Beyond the mid-twentieth century in most westernised countries, a kind of consensus has settled that allows us to compartmentalise many aspects of our identity. We can choose to marry and have children and work in a respectable occupation whilst living as a woman at the weekends in the privacy of our own homes. We can choose to fully opt into gay and lesbian lifestyles or one of their many substrata complete with their own dress and value codes, sexual and social mores. We can opt to be fiercely heterosexual and do so in a way that ranges from homophobic lout to liberal gentleman; chic feminist career woman to silicone-implanted gold digger.

Strangely, the only option that does not seem to have easily materialised is the promised effortless fluidity of a universal bisexuality offered in the Utopian interpretations of early psychoanalytic theory. It's no secret, for example, that gay identities have potentially become lust as restrictive as the straight-jacketed heterosexual male identities they once sought to challenge.

Hernan Bas' work understands and assimilates all of this, opting instead to draw on the visual culture of a strange period of transition in which things were momentarily in flux, when events might have taken another route envisaged in the heady decadent fantasies of its own dreamers. There is a means by which he places us voyeuristically into the position of Huysmans, Wilde or de Lautréamont reworked with a contemporary consciousness.

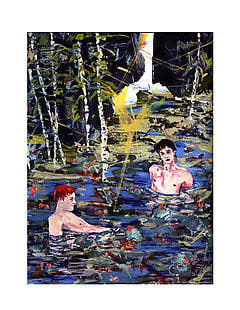

In his works, there is an almost contradictory impulse. On one hand there is a fevered earnestness in the representations. He offers us visions of androgynous boys bedecked in the pearly swathes of accoutrements worthy of the florid styling of any Aesthete: a dying dandy swoons, half-Chatterton, half-Sleeping Beauty; or a youth with pouty lips looks out from a rich tapestry, his Botticelli-esque water chariot drawn by swans. With an art historical awareness, we cannot help but find such overwrought camp desires ironic and amusing. Nonetheless, Bas intentionally reminds us that they really meant it at the time. And, by association, that it might be a manifestation of a drive in many of us that is merely restrained by orthodoxies of taste and fashion rather than natural predisposition.

Such source material for Bas' work arose in circumstances that are very different from our own. This is something that is easily forgotten if we transhistorically project our contemporary values and social structures onto the work. Magnus Hirschfeld eventually offered the well-presented case for the evolving notion of a 'third sex' in 1922 that conceptualised gay and lesbian identities as a separate entity outside of traditional male and female roles and sexual identities. It was probably inevitable that sexual and gender identity would exist on a continuum and as pastiches before this.

The foppish dandies of Wilde or Huysman's circles had no notion of 'gay'. Instead, they had to grapple to express their feelings and desires for their own sex in an age when male and female identities were a package deal when rigid sexualities, dress and behaviour codes summarised a person's social identity. Perhaps this accounts for some of the literality in the depictions of an idealized, new kind of male that arose from within these pre-gay demimondes. They often foreground strongly superficial features such as body or face shape and the cut of clothing associated with the two respective sexes in one individual. We read of boys with the lithe athletic bodies of Greek athletes who have the curly hair and bee-stung lips of the female ideal of the day. We find illustrations of gamin young men with almond eyes and clothing - though ostensibly male - bearing the nipped waist or extravagant fabric of a desirable young woman. We stumble across paintings and sculptures of teenage boys draped in poses more normally associated with nymphs, the feminine aspects of their physiques emphasized.

And, of course, we know something of the older men poring over these idealised visions of pretty boys. All of the evidence from literature and art points to them envisaging themselves as a strange concoction of older dominant gentlemen and opera diva. Depictions of them also show a different odd mix of the male and the female: distinguished men with moustaches, but moustaches that resemble a Gibson girl's coiffure; men in the expensive coats of a gentlemen, but coats made in a fur usually worn by a lady. Perhaps within these expressions, we see the tensions pulling the kinds of men whose visions permeate into Bas' work. Most, coming from the aristocracy or gentry dutifully fulfilled their functions as married men and raised families. And there is a lot of evidence to suggest that they were unwilling to let go of the traditional social status accorded to them for fulfilling their roles as pater familias. Wilde, of course, stands out for making the fatal error of thinking he could persuade Victorian society to accept his vision in which same sex relationships might be accorded a status comparable with marriage. For the rest, even notorious pederasty would be tolerated as long as it was confined to the secret boudoirs and soirees of their own invention. Private and locked away from the world, it was somewhat inescapable that this would take on the unbridled gilding that we now associate with the visual cultures of these luxurious underworlds.

The mechanisms by which the work of Hernan Bas offers a revision of such aspects of this period and its demimondes is complex. It appears to both endorse and critique the context from which it arose. Perhaps it is in this ambivalence that we fully understand its value in a contemporary art context with all of the lessons learned from Post-Modernism.

Certainly, Bas is often eager to collude with the viewers historic role as a voyeur. He places us in contexts in which his pretty young men are undoubtedly fresh meat for our implied camera. And, if traditions in painting offered a comparable position pre-dating a camera, then it is important that we remember that this period was one in which various seminal experiments that would later prompt numerous questions about photography's relationship to 'high art' were making their debut. In particular, the works of Baron Wilhelm Von Glaeden spring to mind.

Von Gloeden's early erotica of naked boys with pretensions to an Arcadian idyll bear marked similarities to the way in which Bas presents his youths for our scrutiny. The same androgynous physiques and languid poses dominate.

Bas' evocation of Von Gloeden or his contemporaries is not unintended. Yet, within the construction of the work through the medium of painting, Bas seems to underscore a number of points. Most obviously, he draws our attention to the ethical question of our position as voyeurs, as consumers of human flesh. The association with Von Gloeden's heritage might force a refreshing honesty about the nature of human desires, but it nonetheless reminds us of the political implications of exploitation. But perhaps more importantly, Bas seems to be making a point about the medium itself, floating a suggestion that painting by its very nature and through its traditions is able to contain and express certain ideas beautifully and safely that readily degrade into something altogether less savoury when transposed to certain other image-making activities.

Of course, this does not mean that he is without insight into the position of painting that, despite its exulted history, is not beyond exploitation and collusion with the political status quo. His canvases tend to be small, domestic, perhaps the scale of work that we associate with the kinds of private collections made by decadent Uranian gentlemen of means who would have commissioned them for their own private delectation, seamlessly fusing this status as those who could afford to own art and simultaneously satisfy their own human desires.

Maybe we can even read it as a wry commentary on the status of painting today. One of the functions of paintings hung in domestic settings – salons, halls, dining rooms – in the nineteenth century was to demonstrate that the householder was of an economic status to own art. Beyond the issues of being able to afford art, lay the more complicated matter of owning art that was in good taste or demonstrated the power of influence to own a work by a renowned painter. Renown and acceptance might be the only line dividing the actual imagery used by painters; one depiction of an androgynous boy fully embraced by the institutions of the day, another sensibly relegated to private quarters. Perhaps Bas reminds us that certain things are not so different now.

But, by contrast, in the world beyond, a world in which we more easily have access to images that would once have been confined to private domestic spaces, it is not only the decadent rich with sufficient means that partake in this dubious celebration of pretty boys. Perhaps we have all become guilty of ogling.

Hernan Bas was born in Miami, Florida where he lives and works. In addition to numerous group and solo exhibitions in top commercial galleries around the world, he has shown in a broad range of international institutions and private collection spaces. These include The Moore Space, Miami; Museum of Contemporary Art, North Miami; Aspen Art Museum, Aspen; Haifa Museum of Art, Haifa; Deste Foundation, Athens; Schirn Kunsthalle, Frankfurt and The Saatchi Gallery London. His work was included in the 2004 Whitney Biennial Exhibition.