A Cultural Lesson at The Top of the Stairs

By Blake Gopnik

Washington Post Staff Writer

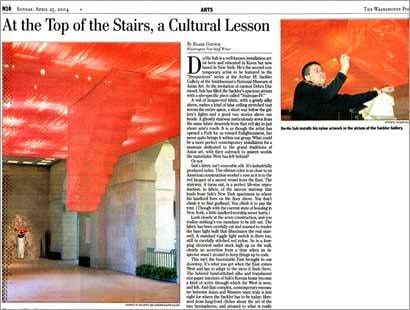

Do-Ho Suh is a well-known installation artist born and educated in Korea but now based in New York. He's the second contemporary artist to be featured in the "Perspectives" series at the Arthur M. Sackler Gallery of the Smithsonian's National Museum of Asian Art. At the invitation of curator Debra Diamond, Suh has filled the Sackler's spacious atrium with a site-specific piece called "Staircase-IV."

A veil of lacquer-red fabric, with a gently silky sheen, makes a kind of false ceiling stretched taut across the entire space, a short way below the gallery's lights and a good two stories above our heads. A ghostly stairway meticulously sewn from the same fabric descends from that red sky to just above arm's reach. It is as though the artist has opened a Path for us toward Enlightenment, but never quite brings it within our grasp. What could be a more perfect contemporary installation for a museum dedicated to the grand traditions of Asian art, with their outreach to unseen worlds the materialist West has left behind?

Or not.

Suh's fabric isn't venerable silk. It's industrially produced nylon. The vibrant color is as close to an American construction worker's vest as it is to the red lacquer of a sacred vessel from the East. The stairway, it turns out, is a perfect life-size reproduction, in fabric, of the narrow stairway that leads from Suh's New York apartment to where his landlord lives on the floor above. You don't climb it to find godhead. You climb it to pay the rent. (Though with the current state of housing in New York, a little landlord-worship never hurts.)

Look closely at the sewn construction, and you realize nothing's too mundane to be left out. The fabric has been carefully cut and seamed to render the bare light bulb that illuminates the real stairwell. A standard toggle light switch is there too, still in carefully stitched red nylon. So is a four-plug electrical outlet stuck high up on the wall, clearly an accretion from a time when an inspector wasn't around to keep things up to code.

This isn't the Inscrutable East brought to our doorstep. It's what you get when the East comes West and has to adapt to the mess it finds there. The beloved hand-stitched silks and translucent rice-paper interiors of Suh's Korean home become a kind of scrim through which the West is seen, and felt. And that complex, contemporary encounter between Asian and Western ways truly is just right for where the Sackler has to be today: liberated from long-lived cliches about the art of the two hemispheres, and attuned to what is really coming out of their current collision.