The New York Times

August 10, 1997

A Month in Shaker Country

By Kay Larson

Last summer, the artist Mona Hatoum gave a tour of the dark Shaker attic in Sabbathday Lake, Me., that had been her studio for a month. In it were fragile, small things. Green and yellow noodles had been woven together into a swatch of edible homespun. Dots of shimmering jelly gathered weblike on a tiny window, the result of squeezing Vaseline through the holes in an old metal pie plate. A sifting of powdered sugar over the springs of a wooden baby's crib left delicate diamond shadows on the whitefilmed floorboards: vanished childhood

limned in pixie dust.

Ms. Hatoum's sweet, simple powder outlines an old ethos of nurture - a glimpse of disappearing farm life centered on living things. Vanishing like the Shakers themselves, one might say, although, the remaining seven men and women who live here and still practice the faith pray otherwise.

Ms. Hatoum and nine other artists spent a month each at the Shaker farm between May and September of last year, sharing work and worship with the only living members of a religion that a century ago numbered several thousand followers. (All other Shaker villages are museums.) The artists are as esthetically diverse as any in the international contemporary-art world: Kazumi Tanaka, Chen Zhen, Domenico de Ciarlo, Jana Sterbak, Sam Samore, Janine Antoni, Nari Ward and Adam Fuss. The photographer Wolfgang Tillmans made repeated visits over a year to capture the warmth of the Shaker sense of community.

The art that came out of this exchange is being exhibited in "The Quiet in the Land," which opened yesterday at the Portland Institute of Contemporary Art at the Maine College of Art. The show continues though Sept. 21 and a version, with Shaker objects added, will be shown at the Museum of American Folk Art in New York in 1999.

Shakers trace their beginnings to Mother Ann Lee's schism with the Quakers in 18th-century England. The Sabbathday Lake community still honors the rules of monasticism and celibacy she established when she led her followers to New York State in 1774. The artists fed sheep, planted herbs, hayed the fields, sliced veneer for bentwood boxes, scraped paint off the original picket fence outside the 1794 meetinghouse. At noontime dinner they bowed their heads for grace, then laid into the scalloped potatoes and ham, apple pie and ice cream. On Sunday they struggled to follow the Shaker songs of joy and redemption, embracing emotions so raw, uncompromising and unadorned that to modem ears they sound positively radical:

Love is little

Love is low

Love will make our spirit grow

Grow in peace

Grow in light

Love will do the thing that's right

The old Shaker way, preserved in museum enclaves throughout the farm, was achingly plain and - at least in material terms - unimaginably bare.

But what of the inner life? By its nature it can't be viewed, yet the pursuit of it shapes the outer. Here artists and Shakers discovered a commonality, surprising nearly everybody.

"The artists and Shakers are quite similar, it seems to me, but I haven't quite grasped why that is so," said Brother Alistair Bate last summer In the Shaker store. At age 32 he is the youngest Shaker, and the newest, having completed his novitiate year last October. In the beginning, he said, everyone felt some trepidation, but it quickly disappeared.

"Although we may speak a very different language, there is some sense of just naturally liking the son of people who are involved in this project. I couldn't put a finger on it, but on a human level we've been getting on very well. We have our eyes on goals, and we are quite devoted to our paths."

The tour of Ms. Hatoum's studio revealed a startling implication of violence; a kitchen colander converted into a land mine by a lethal-looking array of bolts and nuts. On the porch afterward, Ms. Hatoum described the haze of painful identities that clouds her baby years. She was born In Beirut to an exiled Palestinian family of Greek Orthodox Christians. Her father, she said, received the Order of the British Empire for his work with the British mandate In Palestine. She learned Arabic and French at a Greek Orthodox school. On vacation in London when war broke out in Lebanon, she put herself through the Slade School of Art. This fall she is having a solo exhibition at the New Museum of Contemporary Art In New York.

Anguish and loss pervade her work, which has included menacing beds, prisonlike cages and prayer rugs made of plastic entrails (so that to pray is mayhem). "I've always been completely against religion because I grew up in a place torn by terrible schisms," she said. '"I refuse to read the Bible."

Drawn instead to transcendental meditation, Ms. Hatoum meditates morning and evening. "Being spiritual is experiencing something for yourself - the spirit that moves everything around you," she said. "I don't ask myself too many questions about what it is, but I know It's there."

Preparing to leave Sabbathday Lake, she had been depressed and unnerved: sleeping in the afternoon, feeling lost. Her month with the Shakers was a precious interlude of peace, she said: "This community lives its spirituality in everyday life. You feel it in every action they do, their generosity, their openness, their straightforward behavior toward us. There is no fear. As soon as something comes up they deal with it right away. I feel they've adopted us as their children,"

Later, on the way to the airport, she dissolved into tears.

RULES FOR DOING GOOD

Do all the good you can,

In all the ways you can,

To all the people you can.

In every place you can,

At all the times you call,

As long as ever you can.

The Rules, modestly framed, preside over the little room where the women wait 10 enter the dining hall. (The men cool their heels at the other end of the building; Shakers have always separated the sexes.) There are two doors on the meetinghouse, and two sets of steps leading to them. There are also two heads of the community; Sister Frances A. Carr and Brother Arnold Hadd, who share duties and leadership roles equally.

In her Shaker-furniture-filled office, Sister Frances explained that accepting artists into their closeted monastic life was at first a shocking idea. The community considered it only because of their 25-year friendship with the Shaker expert Gerard C. Wertkin, director of the Museum of American Folk An in New York.

He called one day to introduce France Morin, an independent curator formerly with the New Museum in New York, who came to the Shaker Village with an idea for a collaboration with artists. "Nothing like this had ever been tried before," Mr. Wenkln says now. "It was either going to work or It wasn't,"

The Shakers at first said no, then maybe. After Ms. Morin made more

than half a dozen visits, with artists in tow, the Shakers said yes. Sister Frances explained that it came down to trusting the people. "We don't all understand every bit of their art," she said. "But we like the people so well that it has given us the desire to learn more about what makes them the way they are."

The differences between artists and Shakers seem not so significant, Sister Frances continued. "One of our first brothers said, in dealing with crosses - the cross is anything that is hard to accept - make all of your crosses little ones, and the little ones nothing at all,"

The artists, in turn, could identify with "Hands to work, hearts to God," the classic Shaker axiom.

"The whole mind has to switch through that daily work," said Ms. Tanaka one day, as she carefully stitched a strand of her own black hair into a bird's nest size bowl of the same material "It's fascinating in the way I find a connection to what we do, to making art. I feel I make something because I cannot not make it."

Ms. Tanaka's sculptural installation is an observation about the transcendent communion of ordinary Shaker mealtimes. Two tables that double as water filled basins each hold six while plates which float as if levitated by some unseen spirit. Next to them is a ticking grandfather clock entirely hand-carved of wood, and a set or circle drawings made by fermenting a mixture of coffee and milk, revealing the Invisible forces of nature through meticulous attention.

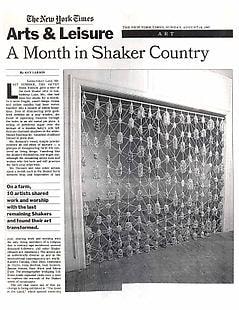

The unbroken circles of old Shaker bottles caught the eye of Mr. Ward, who is perhaps best known for his rank-smelling, greased limousine In the 1995 Whitney Biennial. Born In Jamaica, Mr. Ward is the only artist among the 10 who remains in the faith he was grew up in (Baptist, with reservations). The bottles he excavated from the Shaker dump. shattered everywhere but their circular mouths, seemed like a metaphor for the endurance at the spirit. He wove them into a glass curtain.

The sculptors were inevitably drawn into the interplay of visible and invisible. Mr. Zhen, born In Shanghai, is keenly aware that as he said one day, "this extraordinary Shaker experience is a Western spiritual experience," Before he Immigrated to Paris in 1986, he spent six months Iiving with friends in Tibetan Buddhist monasteries. "It was great to live in so simple a place, with such a spiritual language," he said. "From them I learned to walk: they walk several hundred miles to go 10· temple." He learned 10 Sit, he said, from the Shakers, who "spend a lot of time in chairs praying and singing," His installation incorporates 10 Shaker style chair backs enclosing a woven seat that doubles as a meditation platform. A leap of faith and imagination is the only way to get inside.

Mr. Fuss spent his month at the Shaker farm gathering ladders which he prized as examples of Shaker "twoness": square, strong, upright, eroded by hard use. Exposed directly on photographic film, the ladders became photograms cut out of thin slightly luminous, almost invisible white silk lacked 10 the off white walls: hard work transfigured.

The performance artists, attuned in the immaterial sought out the place of communion that Shakers feel is their true center. Ms. Antoni, who has been attending Quaker meetings, strapped on a video camera and set herself spinning in the meetinghouse, seeking the ecstatic communion that Shakers exhibited when gripped by the Holy Spirit.

Mr. de Clario's lifelong search for spiritual Immersion has led him through Catholicism and Buddhism to the poetry of Jalal·al-Din-Rurnl, a Sufi mytic On his first day at the farm, Sister Frances look him through the Shaker basket storage rooms. Each day after, he painted the Shaker landscape with a basket over his head, seeking that place of darkness and unknowing common to all religions: painting the inner realm, blind to the outer.

Mr. de Clario wore the basket in a performance on solstice night in the meetinghouse. From dusk until dawn, he played unscripted chords

on the piano - the blinded seeker exploring the keys, querying relentlessly, going nowhere - searching for the moment when every distinction dissolves and the music beats directly on skin.

And deep in the night, for those who kept vigil with him, there it was. On the edge between sleep and waking, a seamless interval arises, without thought or thinker, player or played, where each note is momentous and of no duration, and sound flows in pulses and crest of pure luminosity.

Nothing is left, then, but the doing.

The paintings are on exhibition in Portland, and the solstice performance has been packaged as a compact disk. These artifacts may be just a thin reminder of the true ecstatic experience. That's the seeker's plight - but it's also where the promise lies.