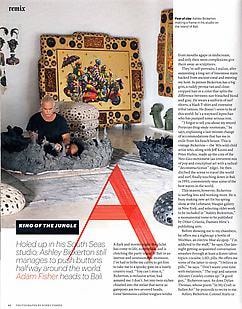

King of the Jungle

Adam Fisher

Holed up in his South Sease studio, Ashley Bickerton still manages to push buttons halfway around the world.

A dark and stormy ngiht: the cliché has come to life, zombielike, and is clutching the party island of Bali in an intense and unseasonable monsoon. I’ve had to bribe my cabby to get him to take me to a spooky gate on a lonely country road. “You can’t miss it,” Bickerton, a reclusive artist, had assured me. I don’t. Set into twin niches chiseled into the stelae that serve as gateposts are two severed heads. Gene Simmins-caliber tongues write from mouths agape in mid scream, and only their neon complexions give them away as sculptures.

They're self-portraits, I realize, after summiting a long set of limestone stairs hacked from ancient coral and meeting my host. In person Bickerton has a big grin, a ruddy perma-tan and closecropped hair in a color that splits the difference between sun-bleached blond and gray. He wears a uniform of surf shorts, a black T-shirt and extensive tribal tattoos. He doesn't seem to be of this world: he's a wayward leprechan who has pumped some serious iron.

“I forgot to tell you about my retired Peruvian drug-mule roommate," he says, explaining a last-minute change of accommodations that has me in exile from his beach house. This is vintage Bickerton - the '80s wild-child artist who, along with Jeff Koons and Peter Halley, made up the core of the Neo-Geo movement (an irreverent mix of pop and conceptual art with a radical "deconstructionist" edge). He then ditched the scene to travel the world and surf, finally touching down in Bali in 1993, conveniently near some of the best waves in the world.

This season, however, Bickerton is surfing less and working more. He is busy making new art for his spring show at the Lehmann Maupin gallery in New York, and selecting older work to be included in "Ashley Bickterton," a monumental tome to be published by Other Criteria, Damien Hirst's publishing arm.

Before showing me to my chambers, he offers me a nightcap: a bottle of MixMax, an electric blue alcopop. "I'm addicted to the stuff," he says. Our latenight getting-acquainted conversation smashes through at least a dozen taboo topics: cocaine, LSD, pills. He offers me some of the latter to sleep. "I believe in pills," he says. "Don't waste your time with melatonin." The yogi and satanist Aleister Crowley comes up: "A good guy," Bickerton says. As does Dylan Thomas, whose poem "In My Craft or Sullen Art" he proceeds to recite to me.

Ashley Bickerton: Colonel Kurtz or Paul Gauguin? Among the art elite who remember him and consider the disturbing and often perplexing stories that trickle back from his South Seas studio, that is the oft-debated question. He was the prototypical '80s art star: Cal Arts degree, friends with JeanMichel Basquiat and Keith Haring, married to the photographer Jessica Craig-Martin, making work that was instantly recognized as postrnodern, a decisive and necessary break from the arid minimalism of the time. "1 just got tired of gray cubes," he says now. "I thought, Why not rum it inside out and fill it full of the moment?"

Bickerton's first solo show at the Sonnabend gallery, in 1988, was of sculptures plastered with corporate logos and signed "BICKERTON" in a groovy typeface that would not be out of place on a surfboard. It was very clearly a critique of the commodification of art, culture, even identity. Other works from around that time were darker and drove the point home even harder. They were sculptures that looked like survivalist gadgets straight from Q’s secret workshop. One had a built-in price tag: a digital counter in the side that ticked upward at an alarming rate. Another had caches of seeds hermetically sealed behind glass: arks for replanting the world in case of a biblical flood or a Soviet fi.rst strike? Whatever it was, Bickerton says, "I made a lot of money in the '80s." He and Craig-Martin spent it traveling the tropics and buying aboriginal masterpieces.

Then came Black Monday in 1987, and divorce. Broke and a little bit broken, Bickerton left Manhattan determined to travel and to live out of just two suitcases: one for his art supplies and the other for everything else. "I grew up in Hawaii," he says, "and I didn't become an artist to move to Williamsburg."

The next morning I discover I'm indeed a very long way from Brooklyn - I'm inside the walls of a tropical hill fort, some sort of Polynesian acropolis. The walled compound, Bickerton says, is his own design: "I plan to die here." He chose the relatively isolated Bukit region deliberately. "I wanted a refuge where I have a lot of sky and sea," he says. He shows me around the place, pointing out architectural quotations from allover Polynesia and beyond. Sharpened tree trunks jut out of walls just like at the great mosque of Djenne. Other details are inspired by a village outside of Lhasa. The curlicue tusks sprouting from the roofs? From a Viking long ship, while the houses themselves are patterned after the clan dwellings of the Dayak headhunting tribes in Borneo. "It's tribal vernacular," Bickerton says, "with infidelity."

The topic of fidelity is raised again when we stop before a long, glittering silver sculpture that dominates the breezy, wall-less living room. "I bought it at a charity auction," he says. It's the work of a well-known Indonesian artist who, it is alleged, is his wife's new man. This is where Bickerton's gleeful perversity erupts into full-fledged pathos. "We are just one big bohemian family," he shares, "and now she has run off, leaving me with this reprobate 13-year-old boy." Django, Bickerton's older son, has lately turned into something of a wild child himself, crashing a motorbike and getting into trouble at school. Bickerton has two young boys. Django is a product of his second marriage, to a Brazilian woman. Kamahele, 5, is from his third wife, the one who was absent during my visit.

"All my marriages last six years," Bickerton concludes with sadness as we reach his studio. The monsoon has flooded the floors, but at least the walls are dry. There's a monumentally large portrait of Damien Hirst - surrounded by his family and done in the colorsoaked, Gauguin-influenced style of Bickerton's last show, which was mostly about living in one big happy extended brood. (Despite residing in Bali, he has made friends with art stars like Hirst, Matthew Barney and Takashi Murakami.) Stacked in the corner are large sculptural frames, drilled out like sea sponges and sprouting horns shaped like bits of coral. The frames will buttress a series of works: heavily manipulated photo portraits of Kamahele and Django posed as feral children. The coming show will be "Lord of the Flies" set in the neon jungle of Bangkok after dark. "I shot every squalid neon sign in Thailand to get that effect," Bickerton says.

His last show's themes of fertile bounty have given way to those of wayward youth, budding sexuality and tawdry vice. So which is it, I ask: Gauguin or Kurtz? Bickerton dismisses the Kurtz comparison out of hand, saying that the real influences are not the works of Joseph Conrad but Paul Bowles and Malcolm Lowry. And "Paul Gauguin was after the truth," he says, flattered. "I am not." What he is, he explains, is misunderstood. "I have no shame about being willing to seduce my viewer. Some see it as gaudy, some see if for what it is: babies, tarts, bars .... " He stops talking for a moment, a rare event in Bickertonland. And then: "Fecundity!" He's pleased to have found just the right word. "But I always go back to the same idea: All these beautiful people die," he says. "For the moment they are sparkling, but they die."