By Amy Larocca

Juergen Teller, the photographer, has spent much of this summer Tuesday editing a shoot commissioned by W Magazine about the art world in New York. The star of the shoot is the 47-year-old actress Tilda Swinton, who has been dressed up as everyone from an artist to a gallerist to an insecure collector mid–Botox procedure. She's accompanied by artists like Rachel Feinstein and collectors like Renée Rockefeller. The whole thing looks fairly dark; the lighting is not gentle or flattering, and if any of the subjects has a pore, or a sagging breast, well, there it is.

"Most fashion photography is done by gay people finding women sexy," Teller says, "which is sort of not sexy at all, at least to a heterosexual man. She's so retouched, so airbrushed, without any human response at all, and, well, you don't really want to fuck a doll."

Teller, who is a heterosexual man, is sitting on the patio of his West London studio-house wearing mirrored aviator glasses, spiky hair, a shiny gold chain around his neck, and a great big Rolex on his wrist. He's circular, with a round head, round belly, and round blue eyes, and he smokes almost constantly—Marlboro Lights with one of those giant European SMOKING KILLS warnings on the pack. The building, which he renovated completely two years ago, features a complicated number of levels: The garage is below the living room and the photo studio is sort of below and beside all that, and from the studio you have a perfect, head-to-toe view of the outdoor shower.

"I just turn the page," Teller says of those very glossy fashion shots. "It doesn't really interest me very much. My work has nothing to do with that. I just really like women, and I like men, and I like children, and I like eating, and I like doing everything. It's something real. I'm for the individual human being, not some plastic figure some gay guy thought out. That's valid for something, but it's not my cup of tea."

There is grit to a Juergen Teller photograph, even when it's one of his lucrative high-fashion ads. A kind of raw, what-you-see-is-what-you-get sensibility that shows the sometimes very ugly side of a supposedly beautiful business. The photographs are undeniably sexy, but sexy in the sense that you can practically smell them. And they don't, necessarily, smell like expensive designer perfume.

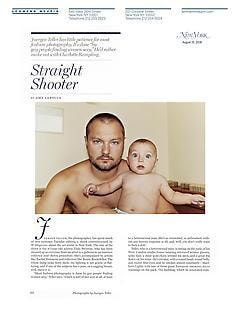

All this rawness is not presented as critique; "Look," Teller says, "I have a Mercedes. I wear a Rolex watch. I have no problem with the selling of things." Rather, it's offered up mostly as realism: Here, the pictures say, this is what people look like. Sometimes beautiful, sometimes tragic, sometimes kind of gross. The pictures can be funny, too. Commissioned to shoot fine jewelry for Phillips auction house, Teller piled diamonds on members of his own family, from his infant son, Ed (adorably bundled into a Motörhead onesie), to Uncle Arthur, visiting from Germany at the ripe old age of 73.

"Why not?" Teller says, deadpan. "My family likes jewelry."

He photographed Angela Lindvall with a mound of white Champagne foam coming out of her crotch and named it New York, Paris, Milan I'm Coming. He named another series "Fashion Wank."

Rather than saturating the colors and bleeding his image off the edge of a page, as is typical for a fashion shoot, Teller uses a raw flash that blasts his subjects and keeps his colors soft and somewhat muted. And the pictures are always surrounded by loads of white space; for the W story, Teller will leave a number of pages blank. Sometimes the models in Teller's pictures are tiny and distant, the color and sheen of their clothes nearly imperceptible.

But perhaps most rare for fashion photography, Teller's pictures are absolutely never retouched. "I'm interested in the person I photograph," he says. "The world is so beautiful as it is, there's so much going on which is sort of interesting. It's just so crazy, so why do I have to put some retouching on it? It's just pointless to me."

"There are elements of Beckett in Juergen's work," says Dennis Freedman, the creative director of W. "It's a very serious business, but there's no question that if you think about life in a certain way, you come to the realization that there are deep questions about what we are all doing here. Juergen touches on the futility of it all—of trying to look beautiful, the futility of trying to keep up your sagging breasts or of fitting into a certain dress. So much fashion photography builds this false sense and maintains the myth. Juergen's pictures cut through all that, but they're not depressing. What's really depressing is not Juergen's pictures, but the mindless objectification of women as clothes hangers who pose and wear clothes, but there's nothing to the picture apart from that it's a sales tool."

Which, of course, in the complicated, push-pull world of commercial seduction, makes them extremely effective as sales tools. "I'm interested in what attracts somebody to a product," says Teller. "Sometimes it's not necessarily the product itself. It's similar to when you go to the cinema and you watch a movie and you're like, Oh my God. I want to feel something like that. That's what I have as a double-page spread in a magazine. It's not I want to be that. It's I want to feel that."

Models are not of tremendous interest to Teller. They were, once: In 1998, Teller found himself so deluged with models landing on his doorstep (agencies were hoping he'd "discover" another Kate Moss, as he was one of the first photographers to document her crooked beauty) that he began keeping a record of the visits. He put an ad in a paper for even more models, and suddenly his doorbell was ringing without interruption. He snapped each girl, standing so vulnerable there on his stoop. The result was a gallery show of the photographs—each printed identically small—and eventually a book called Go Sees: Girls Knocking on My Door.

"I wanted to show everything," he says of the experience. "Some people are very at ease with themselves and enjoy being a model, and you can see that in the pictures. Some people are not, and you can see how insecure they are. It's really dangerous and weird. And I wanted to show the kind of power you have as a photographer, and the dodgy side of that. You have to be correct with them; otherwise, it's just awful."

So Teller shot them all: Sophie Dahl dropped by, chubby and adolescent, and so did Eva Herzigova.

These days, Teller prefers quote-unquote interesting women: Cindy Sherman, Rachel Feinstein, Laura Dern. If he does shoot models, they are older (ideally over 20): Mariacarla Boscono, Angela Lindvall, Kristen McMenamy. They are women with stories and strength. Teller knows them already, or he gets to. They often eat together, preferably something sloppy. Meal sharing, he explains, is deeply important to his process—spaghetti nero, with its muddying effect on the lips and teeth, has become, for Teller, something of a leitmotif.

"These women have experience in life and you can really talk to them about what you're trying to achieve," he explains. "It makes a hell of a lot more sense to make an ad which creates a fantasy about those women than about a bunch of young Russian models looking all doodly-doo." For a recent Vivienne Westwood campaign, Teller all but ignored the model and instead photographed Westwood herself. She appears pale and crinkly and not-skinny and absolutely, completely self-possessed. She is gorgeous. But also—and this is important—he has not exactly shattered the rules of fashion: What she represents is every bit as unattainable, if not more so, as being tall and thin and 16.

Teller arrived in London just over twenty years ago, a befuddled German photo-school grad with a thing for grunge. "I wanted to learn English," he says of his reasons for leaving Germany, "and I didn't want to join the army."

He started out photographing musicians like Björk and Kurt Cobain. His photographs appeared mostly in magazines like i-D and The Face, which were, in late-eighties London, as influential as any style magazines have ever been.

He met and fell in love with a stylist named Venetia Scott, a square-jawed, no-nonsense beauty who looks something like a photograph by Dorothea Lange. They worked together, slowly sorting out what they considered beautiful: "We just kind of very naïvely and innocently had a lot of time on our hands," Teller says, "and we thought very long about what kind of girl or woman interested us and what we wanted to do. Sometimes we did one fashion story a year, and sometimes two. It was really slow, but it was great. We couldn't go faster." Fashion was quite glossy and supermodel-driven then, but Teller and Scott got hung up on Kate Moss, who was impossibly short and quirky by the standards of the time. "It was a bit scary for the Vogue people," Teller says. "We were kind of free-spirited and hippieish and kind of dreamy." They often shot with vintage clothes because the big design houses—"the Gucci Puccis," Teller calls them—wouldn't loan to them.

But they had worked it out, their idea of beauty: It was young and human, a direct sort of opposition to all that was glamazonian in the world. And it took: By the early nineties, The Face and i-D had moved outside the status of cult and were suddenly being mined for talent by the biggies. Soon, as Teller puts it, "those magazines became mainstream, and now everything is mainstream. The force was too strong not to listen to me. I was able to humanize the person wearing the clothes."

Various Vogues began to hire Teller, and he loved the first-class travel, the luxurious accommodations, the large budgets. But it never felt quite right: "It's too dictatorshipness," Teller says. He found the mainstream editorial take on fashion to be way too camp, and in return, mainstream fashion found Teller way too dirty; they sought to scrub him up, temper the grunge. "They would put me with Linda Evangelista," Teller says, "and Patrick Demarchelier with Kate Moss."

He was far happier finding designers who shared his off-center ideas, like the urban minimalist Helmut Lang. "Juergen has a very strong individual voice," Lang says, "which is a rather rare accomplishment these days. I love his ability to say out loud what other people are afraid to even think." Teller became the documentarian of Lang's designs: "It was natural to have him express the soul of my work," Lang says. Teller's Helmut Lang ads were as clean as the clothes themselves.

In 1997, Marc Jacobs began to woo Venetia Scott to style his collections (she was pregnant at the time with the couple's daughter, Lola, who is now 11). Jacobs and his business partner, Robert Duffy, flew to London to persuade the reluctant Scott, but Jacobs and Teller wound up sharing a smoke out back. "I'd always loved Juergen's work," Jacobs says. "I saw in Juergen all the same things that I was responding to: the imperfection of what's real. It was not perverse at all, it was just my generation's sensitivity to what's attractive and right." There was no money for ads in those days (Jacobs had not yet been acquired by LVMH), but Jacobs turned to Teller and said, "I hear Kim Gordon's been wearing one of my dresses onstage. Can you take her picture?"

Teller photographed the Sonic Youth front woman, and a collaboration was born.

Teller went on to shoot many of Jacobs's friends, and the odd model, for his campaigns. In 2005, he photographed himself with Cindy Sherman, the pair made up to look like pale, terrifying prepubescent twins. He had Jacobs alter his clothes to fit a tiny, eerily adult Dakota Fanning. Most recently, he stuck Posh Spice in a shopping bag. "She is like a product," he says. "And she was in on the joke."

But Teller's most important Marc Jacobs ad, for his own career, anyway, began in 2004 and involves a collaboration with Charlotte Rampling.

It all started when a French actress of a certain age lost it upon seeing some photographs Teller had taken of her. "She said, 'You make me ten years older than I am,' and I said, 'You think you're ten years younger than you are.' And then she sort of kicked me out of her apartment, and I was really sort of devastated. I just thought, This is fucking rubbish—this is really bad."

Despondent, Teller called his friend Rampling, who offered to cook him dinner. They talked about how it feels to be photographed, and how it feels to age. "I just thought, Fuck this, I'm going to photograph myself," he says. And then there the two of them were, in the Louis XV suite of the Hotel de Crillon, with Teller way too fat to fit into any of the Marc Jacobs samples save one terribly shiny pair of silver shorts.

"I thought, Fuck," Teller says, "I don't even fucking fit into these clothes. I'm really fucking stuck now."

So he pulled on the shorts in the bathroom. "I came out and I had my socks on and I had these shorts on and no top, and I just said, 'Ta-da!' And she said, 'Oh my God. What are we going to do?' And I said, 'Well, I don't know. But really, honestly'—and I could hardly bring it out of my mouth—I said, 'I just want to kiss you and fondle your breasts.' And she didn't say a word. She just leaned back in her armchair and went into her handbag and got a cigarillo out and lit it and the air was thick and I was mortified. And then she sort of dragged on her cigarette and said, 'Okay. Let's start. I'll tell you when to stop.' "

The result is an ad that is glamorous, decadent, arresting, and entirely unlike any other fashion advertisement you're likely to see in even the fattest September book.

"For me it was important that an over-60 woman is in a high-class fashion ad, or whatever you call it, and a 40-year-old overweight guy, instead of these anorexic young kids." It's like some sort of avant-garde Dove campaign, interested in amping up the glamour of fashion by removing its artifice but retaining the decadence of an ornate suite in a five-star hotel, all tricked out in the gilty style of Louis XV. Teller was so happy with the ad that he and Rampling returned to the Crillon and continued the shoot, eventually publishing a small book. The photos verge on pornographic: In one, an (uncircumcised) Teller is pissing into an orchid, right beside a rotting bowl of fruit. It's almost as if, by placing himself in the photographs looking naked, pudgy, and often sad, he has removed the sadism inherent in so much fashion photography: If a model is required to look vulnerable, well, then so will Teller. "I'm so used to seeing Juergen's body parts," Jacobs say of the Rampling photos. "When he shot Sofia [Coppola] for the perfume ads, his toes are in, like, every shot. Juergen is Juergen's biggest fan. Every time he sends me pictures, he calls and says, 'Marc. Here are the pictures. They are fucking excellent.'"

Juergen's photographs are autobiographical," says David Maupin, his New York gallerist, "but they are biographical too. They tell you about him, but also about his subjects, also about Germany." Teller's German childhood was far from idyllic. He grew up by a forest near Nuremberg, scene of Fascist rallies and Triumph of the Will. But more to the point, his father was a nasty, abusive drunk. Young Juergen watched a lot of television, which he thinks was his biggest inspiration, visually. "That's where I became physically aware of watching and looking," he says. "Like, on this German crime show there was Nastassja Kinski and she kind of got raped by one of her students, and she was really young and extremely beautiful. That made a huge influence on me." Teller's family expected that he would go into the family business—stringing musical instruments—but he couldn't bear the idea and developed an allergy to the materials, which he now claims was psychosomatic. During Teller's second year in London, his father committed suicide.

A few years ago, right around the time of the distressed-French-actress incident, Teller decided to confront his past. He flew to Nuremberg and photographed himself, naked and squatting in the forest, naked and drinking and smoking on his father's grave. "It was a very difficult picture for my mother," Teller says, "but I was kind of saying, 'Hey, it's okay what you did and I'm still around and I have also my problems in terms of smoking and alcohol, but I'm good.'?"

Teller split from Scott five years ago and has since married the London gallerist Sadie Coles (to understand the smallness of the fashion world, know that she represents other Jacobs stalwarts Elizabeth Peyton, TJ Wilcox, and John Currin). The couple's long-lashed, blue-eyed son, Ed, is now nearly 4, and he shouts, that Tuesday afternoon, to his father, "I love you, Dad. I'm going to the park, but I love you."

Right now, Teller is more into fashion than ever. "It just comes very easy to me these days," he says. "Autobiographical work—photographing myself—made it all much more easy." But he's done shooting himself for the moment, and wants to get back to gorgeous girls and gorgeous stuff. He's just photographed Carla Bruni, which pleased him most because it will impress his mom.

Teller's influence is everywhere. There's a similar rawness in the work of Terry Richardson—"He certainly took some of my ideas," Teller says, diplomatically—but it is not as subtle, as nuanced, as the work of Teller. And it's hard to imagine what American Apparel ads would look like had Teller not come first. "I really like that," Teller says, "because it looks effortless and it looks good and just, frankly, it's girls you want to fuck."

Fashion for Teller remains rich. He's come a long way from being denied by the Gucci-Puccis, and he loves it. "Fashion designers in a funny sort of way are underestimated within their creativity," he says. "It's really quite amazing what they do. They are also very creative." He laughs a bit. "The whole thing is just fascinating to me: What people will do to themselves—and to what extent people do whatever you tell them—is just insane."