Writing about Juergen Teller’s forthcoming exhibition at London’s Institute of Contemporary Arts, ICA director Gregor Muir notes: “whether he is an artist or photographer … or anything connected with such thoughts, can only lead us astray. Teller’s work is about great images.” Indeed, the German-born photographer moves between genres with breathtaking ease. Acclaimed in the fashion world for his Vivienne Westwood, Helmut Lang, and Marc Jacobs campaigns (among many others), Teller has long ago made a name for himself with more personal series of works. “Ed in Japan” compellingly records a trip taken with his wife, gallerist Sadie Coles, and their then-infant son. His private life is also at the heart of Teller’s “Irene im Wald,” which was shot in the forest with his mother in his hometown of Erlangen, and “Keys to the House,” portraits of family and friends in the British countryside.

Whatever the subject (and the preparation these images involve), Teller’s images bristle with raw emotion. They advertise a sense of authenticity characteristic of pictures taken off-the-cuff, on the spur of the moment. Known for never touching up his work, the photographer shows his numerous muses each captured within an uncompromising light: whether Charlotte Rampling naked in the Louvre, Vivienne Westwood flashing a red pube, or Kristen McMenamy baring her anus. Teller is equally challenging with himself, posing shitting in snow, or with his head stuck in a platter of roasted pig. Yet, for all its provocation and surrounding controversy, there’s a genuine sense of tenderness in Teller’s work, a palpable enthusiasm and genuine complicity between photographer and subject. A week before the opening of his ICA show, ARTINFO UK met the man at his West London studio.

I was thinking about your recent projects “Irene im Wald” and “Keys to the House.” How do you link these two series?

I’ve always wanted to photograph the forest. I lived next to the forest, and I very much like to be there. But I was never able to photograph it, because there are so many trees, and for some reasons, I tried too hard. A couple of years ago, when we were renting this house in Suffolk, I started photographing the landscape there, and I was very pleased with the results. Because these Suffolk landscapes worked, that gave me a confidence to go back to the forest, to go back home. I realised it’s when you actually just look and don’t impose yourself too much on it that the pictures come to you. But you have to look a lot. I walked a lot, and I took many, many photographs.

Was the problem the immensity of the forest? Did you feel it would escape you?

Well, I just couldn’t see the wood for the trees. It really helped me to do these simple landscape pictures in Suffolk. And then my mom wanted to join me. She liked that I came back and spent some days with her, going for walks in the countryside. That’s when I started to photograph my mother.

Do you feel that you’ve established a different kind of relationship with her through these images?

Yes, because I wrote a text about it too. It’s in the book, and it will be in the exhibition underneath the photographs. Let’s say it has bridged certain gaps between my mother and me, in a good way. She’s fully behind me now.

Wasn’t she always?

There was a certain question mark. Obviously she doesn’t like certain images, but I believe she is more forgiving now, because she understands everything more.

You’ve been taking pictures of your family for a long time. Do you see your practice, or part of your practice, as a sort of diary?

No. I don’t see it at all as a diary. I have certain ideas, and they are mostly project-based. “Ed in Japan” [2006], which I shot when my son was 11 months, was a journey we took through Japan and that became a book and an exhibition. I wouldn’t just photograph Ed today, brushing his teeth and tomorrow going to school.

Can you tell me about the ICA exhibition?

It has three rooms. All the framed work is pretty much my personal work, and then there’s a small room, the reading room, which will have a table with books of mine attached. On all four walls, I will wallpaper about 700 photographs, from top to bottom. There will be everything: Céline ads, Jigsaw ads, Marc Jacobs ads, portraits, everything like that.

You are showing photographs in several different ways: on magazine-type paper, framed, or in books. Do you think about the final materiality of the image when you shoot it?

Well, there’s always a different reason for a different thing. For example, when I did the picture of Victoria Beckham in a plastic bag with her head sticking out for a Marc Jacobs ad, there was monthly discussion between Victoria, Marc, and me. Then you have to produce the oversized bag, you have to have it built. Then all you do is fly to L.A. and execute it. It was pretty clear that this picture could be something, more than just a silly fashion ad.

Isn’t that always what you have in mind?

Yes, but I knew with this one for sure. This picture is also on the wall on one of the upstairs rooms.

You presented Victoria Beckham in a way completely at odds with the images of her we were used to until then. How did she react to the idea? Did you find that you had to do some convincing to do?

No, the convincing was pretty straightforward. I wanted her to be a product, an accessory in this bag. She understood that very well, and she was laughing with us. But it was difficult for her to agree that I wasn’t going to give her photo approval. Then I said: “Listen, there is this bag, and your legs sticking out and I’m going to make a Polaroid. You can look at the Polaroid and see that there’re nothing hidden in it. I’m not going to put a fucking elephant on top of your head.” I believe that if you are straightforward and honest with your intentions, telling the subject what you want to do, then it’s either a yes or a no. But of course, it depends how you ask. You have to have a certain charm, and ask at the right moment.

Alex Needham wrote in the Guardian that to be photographed by you is “to accept a dare.” Do you agree?

No, I don’t. People take the whole thing far too seriously. It’s just a fucking photograph. Certain people are like: “This is really daring, I agreed to be photographed by you,” and I’m thinking: “Are you crazy? I’m not going to bite your thing off. This is just ridiculous.” And I make them beautiful anyway, I make them interesting and good looking. They are all grown-ups. They have a full understanding of what I’m asking them to do, or not to do. They know what they are running into.

Even when you started photographing, say, Kate Moss when she was a teenager? Did she know what she was letting herself into?

No, when you are young you don’t necessarily know, of course. But my pictures of her when she was a teenager are very naïve, there’s nothing weird about them.

You are one of the photographers who radically changed the way we understand fashion photography. How much of this was an intentional project of yours?

That didn’t interest me at all. It’s just what I do. It’s how I feel, how I see, and that’s what I believe in. I was always on my own on doing it. Then I got a response for it and it grew. I was interested in certain things, working with [former partner, stylist] Venetia [Scott] at the time. It made complete sense for me to work with Helmut Lang, and I worked with him from 1993 to 2004. Working with Kristen McMenamy also made complete sense.

Each time it’s a person, isn’t it?

Yes, it’s all very personal, and a personal response to everything.

You’ve had a longstanding relationship with several of your subjects. Do you feel that it gives you a different eye on them? Does the trust make it easier?

It makes it more difficult in a way, but it’s more interesting certainly. I just like certain people. I like being with them, having conversations with them, having dinners with them, and I like going on an adventure with them. For me, it’s not about collecting, doing celebrity portraits. I’m just interested in each person and it’s exciting to go further with them. And in the end, there’s not that many people you actually like.

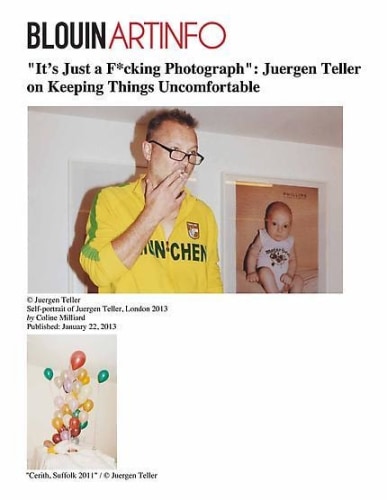

How did you start on your self-portraits?

I was always photographing other people. And at some point, I thought it was psychologically draining. I just wanted to feel how it is to photograph myself, to feel how it is to be photographed by me, the physical act of it, if that makes sense. I was also interested in how it looked, and I enjoyed it for a while.

Do you feel self-portraiture has changed the way you photograph?

It has helped with my subjects. It pushed things a lot more forward. When they are looking at my self-portraits, they really know what they are getting into. I would have never gone so far with anyone else. It certainly opened up.

You’ve got a very particular technique, with two cameras and flash, that you use one after the other. How did you arrive to this process?

It’s getting a little bit too much written about, and all of it isn’t true.

It’s time to put it right.

It has many reasons. It started out with nervousness, and it gives me time to think behind the camera. Then of course, as I’m a professional photographer, there were certainly cases when there was something wrong with the camera, you have to make sure you covered it on both. I also find that it sort of hypnotises the subject, in a very gentle way. If it’s a bigger camera and you have a tripod, take a picture, look at the Polaroid, say: “Oh, the Polaroid looks nice,” and then put the film in, and ask the subject to do the same thing, by the time you take the actual picture, they are completely stiff. I would rather get rid of the whole thing, and just do this [pretending to have a camera in each hand]: “this is right,” this is right, stay like that” — get rid of the whole thing, and don’t make that, what people call “decisive photograph.” There will be a decisive photograph, but it’s more fluid.

You famously don’t shoot on digital cameras. Why is that?

I would like to photograph digital but I haven’t really properly looked, and found a camera which I liked. I’ve never found a camera where the flash works so fast. And I just grew up with [analogue photography], you know. So far for me there was no real reason to change anything. But I’m not really against it.