Home is Where the Ghost is

By: Christie Lee

Long gone are the days when people are firmly rooted in one place. In an increasingly globalized world, the savviest in their fields are expected to shuttle between two - sometimes three or four - cities. Such mobility comes at a cost though, cultural displacement being one.

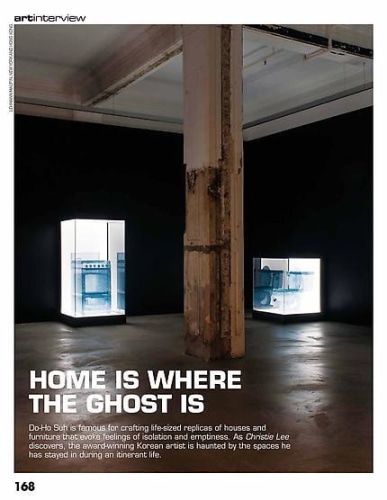

And this is the underlying theme of Korean artist Do Ho Suh's latest solo exhibition at Lehmann Maupin gallery, where mundane everyday objects including the likes of a radiator and doorknob are replicated in translucent polyester fibre. Housed within brightly-lit glass boxes, the 'specimens' - as they are appropriately called - are sublime yet fragile. Encountering these and the crisp air inside the gallery, visitors might feel as if they have wandered into a chemistry laboratory.

Yet, speaking in the posh surroundings of the MO Bar at the Landmark Mandarin Oriental, the sculptor and installation artist explains that each object is charged with personal memories. "They're items which I've spent a decade with in my New York City apartment; essentially I'm inviting the public to visit my place," says Suh. "you can't talk about the personal without talking about the interpersonal, since w're all part of society."

Born in Korea in 1962, Suh's career has been marked by a number of displacements. His father was Se Ok Suh, an abstract painter credited for pioneering non-figurative form in traditional Korean painting in the 1960s. As a child, Do Ho dreamt of becoming a marine biologist, but when his mathematics scores fell short of the mark he took refuge in studying traditional Korean painting at Seoul National University. After the requisite stint in the South Korean army, he went to live in the US, clinching bachelor's and master's degrees in fine arts from Rhode Island School of Design (RISD) and Yale University respectively.

"It's a funny story to tell," chuckles the newly-minted WSJ Magazine's Art Innovator of the Year of this relocation to the US in 1991. "I basically fell in love with a Korean-American artist, got married and followed her to the States. A lot of Koreans go to the States for their studies, but I moved there to start a family, so mentally I had a completely different trajectory."

In fact Suh, whose works are part of the permanent collections at the Museum of Modern Art, the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum and Mori Art Museum, never set out to become an artist. "It was all pretty open-ended for me, even when I was studying at RISD," he recalls. That was, however, before he fell in love with sculpting. "I never worked with traditional art mediums. Even with sculpting, I've always worked with materials that are…more contemporary," he muses.

One of his first sculptures upon graduation was Some/One (2001), a Korean-style military jacket fashioned from 30,000 dog tags, which from afar look like they are inscribed with legitimate names but upon closer inspection are no more than a nonsensical jumble of characters. "Serving in the military made me realize how easily one could be consumed by the system. As an individual, you're insignificant," says Suh of the inspiration behind the art piece. "I wanted to make something for soldiers' bodies, something that is sturdy and shiny on the outside, but which is actually hollow on the inside, since the military is based on the sacrifice and disappearance of soldiers. The jacket becomes the only form of identification when soldiers' bodies are decomposed."

While inspirations for Some/One might have stemmed from Suh's personal experience, the mirror that is half-hidden inside the jacket gives viewers the eerie illusion that they are the ones donning the jacket. It is a rather disturbing message - no matter how much we assert our individuality, we inevitably get sucked into a greater system.

This blurring of the boundaries between the individual and the collective is later echoed in Cause & Effect (2007), in which thousands of tiny men are densely stacked on top of one another. The miniature men motif is also used to explore the relationship between the viewer and artwork. In Floor, the viewer, rendered as a giant, is invited to step on a glass floor that appears to be help up by 2,000 tiny men. Meanwhile, Karma captures the moment at which a gigantic pair of legs appears to be cutting through the gallery ceiling to step on a black puddle of miniature people. It's a sinister image to behold, and one that seems increasingly pertinent in light of the Occupy Wall Street protest and the satellite movements it sparked around the globe.

Mankind's eternal fascination with visualizing time is poignantly - and quite literally - weaved into Suh's ongoing Home and Specimen series; works from the latter comprise his Hong Kong exhibition. "Time is story, which becomes history. The way you live your life creates some sort of a pattern and energy flow within that space," he explains. "By placing the objects in a similar fashion to how they were being placed in my New YOrk apartment, I was hoping to recreate the sense of the space."

It is also the moment at which the intricately-carved exhibits are elevate from the realm of craft to art, when the construction of a coherent narrative demands that we attribute as much attention to the "empty space between the objects" as to the tangible objects.

In opening up his personal life to the public, the exhibition fulfills the audience's voyeuristic desires - but Suh's relationship with these objects is ambivalent: "I've used these objects for about 15 years, so they're kind of intimate, but at the same time they don't only belong to me. It's not like I'm revealing my sexual fantasies."

"The translucent fabric represents something intangible. Something that's there, but not there at the same time," he adds when asked about his choice of material.

Specimen is an extension of his Home series, which began with Seoul Home/Seoul Home in 1999. A replica of his childhood home in the Seongbuk-dong neighborhood was crafted with the help of a 3D scanning machine, before being suspended in the air and draped in monotone Chinese silk. Home within Home within Home within Home within Home, a gargantuan installation which opened at the National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art in Seoul on November 12, comprises life-size replicas of two apartments that the artist had previously resided in.

"What I'm trying to do is memorialize the idea of the home - to carry it with me whenever I go. It sounds like such a cliché, but for me home is ultimately where the heart is." He pauses. "Actually that's a really nice way of putting it. I think it's more accurate to say that I feel like I'm haunted by a space. It's like a ghost, following me around all the time."

In Fallen Star, the sense of displacement is manifested in its most physical form. A house appears to have crashed onto a corner of the Engineering Building at the University of California, San Diego. Visitors gain access to the entrance by way of a winding brick path, flanked by patches of green and two white beach chairs, on the rooftop. The interiors, awash in warm reds, blue and ivory, look cosy enough for a family's living room - until you remember that the house is in fact teetering on the edge of a seven-story building.

While Home with Home evokes a sense of loss and alienation, Fallen Star is about the thrill of living on the edge. And perhaps for Suh, who city-hops between New York, London and Seoul, the two sentiments go hand in hand. When Asked what gives him a sense of belonging to a place, he gives a knowing smile: "Everything is about chemistry. It's alms like seeing somebody."