Ashley Bickerton: Mitochondrial Eve/Viral Mother

By Joshua Mack

From the wall-mounted, industrially fabricated ‘rafts’ decaled with designer-like labels that brought Ashley Bickerton to prominence as a neo-conceptualist in New York during the late 1980s, to the images of a toxic paradise (venal locals and drug-addled sex tourists in vivid blues and greens based on Photoshopped images) he’s created since moving to Bali in 1993, Bickerton has consistently challenged the formal definitions of painting and, by extension, the material and cultural pretensions of contemporary society.

While his elisions and manipulations of media (photography, sculpture, canvas, paint) and his acid critiques of commercialism have become artistic lingua franca, few artists have pursued such issues as relentlessly, or have synthesized them with such aesthetic and conceptual boldness, as he.

His newest work drills down to the origin of all the rot he’s tallied. In Eyeball Painting 2 and Eyeball Painting 3 (both 2013,) cast resin orbs mounted on wooden panels seem to stare out at, and through, their viewers. Their irises, collaged with snippets of the Western canon, such as Picasso’s Guernica (1937) and Bosch’s Garden of Earthly Delights (1503/4), and, in a nod to the universality of ego, Bickerton’s own work, reveal to us what they ‘see’: a history of received cultural sanctities that, rather than enlightening the people who cherish them, provoke violence and arch consumerism.

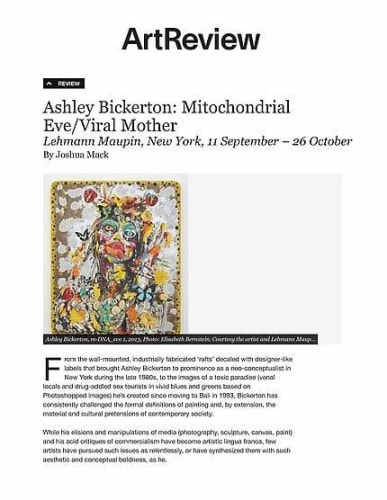

The mother of this world is the corpse-like woman depicted in the series (also 2013) titled m-DNA _eve, in homage to the single African woman from whom all human beings descended. Festooned with necklaces of burned cigarettes and garlands of rotting fruit, she leers knowingly and insatiably at no one and everyone in particular. Picked out in high colours, her printed image mounted on gouged panels, she is goddess of a world awash in junk, the very stuff she’s made of – origin and avatar of the excess appetite that is literally reducing the planet, and her along with it, to ruin. In a religious sense, she is Alpha and Omega.

What saves this work from a scolding tendentiousness is the ironic obviousness of Bickerton’s art-historical references, and a dose of self parody. With their high cheekbones, his Eves have the smack of self-portraits. And, for all their gloppy ghastliness, the paintings have a confounding beauty.

That some of these ideas have appeared

in previous criticism of Bickerton’s work suggests that the toxic aesthetic he owns, and the material and social excesses he both critiques and indulges, have become repetitive themes

of his work. Given his command of materials, his critical eye and evident horror at the suicidal binge our species is on, perhaps it’s time Bickerton worked towards a resolution rather than more seductive but over-the-top trophies of critique.