‘The Painting’s Not Really on the Wall’: Mary Corse on 50 Years of Her Elusive, Seductive Art, and Shows in Los Angeles and New York

By Catherine G. Wagley

In 1967 Mary Corse first came up with the idea to build a cold room to house one of her ascetically minimal, neon-lit light boxes. She imagined giving visitors coats before they entered the chamber. She didn’t get a chance to build the piece at the time, but half a century later, a 12-foot-high, 12-foot-square white cube now stands inside Kayne Griffin Corcoran in Los Angeles, its interior cooled to 40 degrees. The light box hangs against the room’s southernmost wall. In this finally realized version, there are no coats. The chill is part of the experience.

“I had the idea that it would be great to look at this in the cold, because the cold, I’ve since found out, heightens your consciousness,” Corse told me, as we sat in her studio in rural Topanga Canyon, about 30 miles northwest of downtown Los Angeles, on a recent Saturday afternoon, a few days before work on the installation began.

The cold room at Kayne Griffin Corcoran, part of her first solo show there, which is on view through November 11, has a heavy sliding door and an elegant look—brushstrokes are visible in white paint on the exterior. “It’s going to be very quiet,” she said, “just like a wakeup in the cold to look at the white light.”

Corse, who got her MFA from Chouinard Art Institute (now CalArts) in 1968, began making art in the Los Angeles area a few years before then, and has stayed put ever since, working with light and primarily white and black monochromes the whole time. Her best-known paintings are the shimmering white ones she has long made with glass microspheres, the same material used to make traffic signs glow at night. Four feature in the KGC show, alongside the new works she calls DNA paintings, composed of bands of white and bands of small black acrylic squares. Another suite of DNA paintings are on view at Lehmann Maupin in New York, where another solo show runs through October 7.

“Like Athena who sprang from the head of Zeus fully formed, dressed and armed, Corse has been producing mature work . . . since her first show at age nineteen,” curator Drew Hammond, a fierce supporter, wrote in a 2011 catalogue essay. She had an early start: at the private school she attended in Berkeley, her Chouinard-educated teacher taught a tiny class of adolescent students about Hans Hoffman and Willem de Kooning. “I went back and looked at some early work,” Corse said, meaning by “early” the art she made in middle school. “A couple of them had this glowing white cup in the middle of the painting. When you look back and see these little traces of things, you wonder, How long has that been there?”

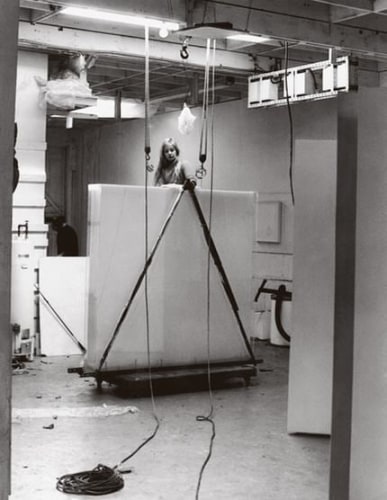

As a student at Chouinard, Corse worked from her own studio in Downtown L.A., building her first light boxes, initially placing fluorescent lights inside Plexi mounted on white-painted, sanded-down wood. Later, she learned to use argon-fueled neon, wirelessly powered by tesla coil generators hidden in a wall or ceiling. Her advisor, Abstract Expressionist Emerson Wollfer, came by every six months to see her work. A photo from 1966 shows Corse sitting and staring up at a light box bigger than she is. It’s suspended from the ceiling via metal cords, and nothing about her industrial set-up looks remotely amateur.

She arrived in L.A. at a fruitful moment. Her fellow Chouinard classmates included Laddie John Dill, Doug Wheeler, Al Rupperbserg—and, a decade before, Robert Irwin, an artist to whom she’s often compared, had gone to the school and was at work in the city. But she didn’t feel part of their world. “There wasn’t a camaraderie,” she said, “especially toward a girl, and I dressed like a girl. It was before Women’s lib.”

By the 1970s, she’d left Downtown, moving with her young children into what she described as a shack in Topanga Canyon. She never had another job besides making art. “I felt like, I’ve got kids and painting,” she said. “That’s two things right there.” This meant that she often just scraped by, trying to manage her art career without much outside help. The L.A. dealer Nick Wilder, who Corse said “didn’t know what to do with what I was doing,” brought New York dealer Richard Bellamy up for a studio visit in the 1970s. Bellamy, an unconventional dealer who had helmed the short-lived Green Gallery in Midtown Manhattan before starting a number of other projects, fell for Corse’s paintings. “Her great beauty and spirit are unbroken by a long series of misfortunes,” Bellamy wrote of her in a letter to a collector, around the time he helped her scrape together funds to build a track system that would hoist the textured clay tiles that made up her “black earth” paintings from her studio floor out to her kiln. “She has the violet glow,” Bellamy continued.

“I was very naive,” Corse told me. “I said [to Bellamy], ‘Sure, OK, you’re my dealer.’ ” Occasionally, he sold some paintings, but he wasn’t known for his financial acumen. “He simply wasn’t interested in making [money],” Judith Stein says in the preface to her recent book about the dealer, Eye of the Sixties, “even as the contemporary art market exploded around him.” Corse put it another way: “I think he wanted his artists to suffer.”

As Bellamy tried to develop a New York audience for her work, the L.A. art world lagged behind. In 1995, Los Angeles Times critic William Wilson, who had been covering art in the city for 30 years, wrote, “Mary Corse has made art here since the early ’60s. She emerged in the ’70s only to get lost in the crowd…” She won a Guggenheim Theadoran Award in 1971, a National Endowment for the Arts grant in 1975 and had occasional solo gallery exhibitions throughout the 1970s, selling work just often enough to keep afloat. But like so many women of her generation, she lacked consistent institutional support. Wilson continued, “This art does not need membership in a category to be interesting. But simply as a fact of its sheer physical existence, it does belong in the annals of California Light and Space.”

Corse has never identified with Light and Space as a California movement. “I’m not a landscape painter,” she told me, as she has told interviewers before. “So if I were in New York I’d do the same thing.” Her work is not regional, in other words. She has also never liked being identified as a “woman artist,” she said. “So I didn’t do all-women shows. That didn’t help me either.” She’s not sure she likes being identified at all. “I don’t really identify even with my name,” she says. “I am not. People say, Are you Mary Corse? [And I say,] ‘Once in a while.’ ”

Back in the 1960s, Corse said that she believed she could somehow escape herself, erasing her hand from her work and thus finding a greater truth. “I was looking for an outdoor reality,” she said. “An objective reality. I was trying to make something true out there.” Around this time, she stumbled upon quantum physics. She needed an electric part to build a generator to keep her light boxes lit, and she had to take a physics test in order to acquire the part. Quantum physics “got me thinking in a whole different way,” she said. “I started to realize how perception, our created reality has more to do with reality—there’s not really an objective reality out there.” She returned to painting, and stopped trying to remove all traces of strokes.

In her white on white paintings, four of which hang on the walls surrounding the cold room at KGC, the brushstrokes create a trippy experience. Made with the microspheres, they look different from every angle. “See how it changes sometimes in the light, and sometimes it doesn’t?” Corse asked, walking along a wall of her studio that held one of the large new white and black DNA paintings that would soon leave for the gallery. The small, sleek acrylic squares that make up the black bands resemble confetti—there’s precision to Corse’s work, but not necessarily over-seriousness. It’s OK if, from one angle or another, the work looks like it’s drenched in glitter. “The painting’s not really on the wall, it’s in your perception,” she said. “It also brings in time—the time to walk along the whole thing. They forgot it should be Light and Space and Time.”

None of the other artists prominently associated with Light and Space returned to painting. Turrell, Irwin, Dewain Valentine, and Craig Kaufman all left the canvas behind. But Corse doesn’t see her early attempt at objectivity as antithetical to her subsequent paintings. “It’s odd, but it’s almost like everything is true in art,” she says. “Just because you do one thing, say you make a black painting, doesn’t mean making a white painting next invalidates it. It’s all true. It’s fascinating.”