Gilbert & George

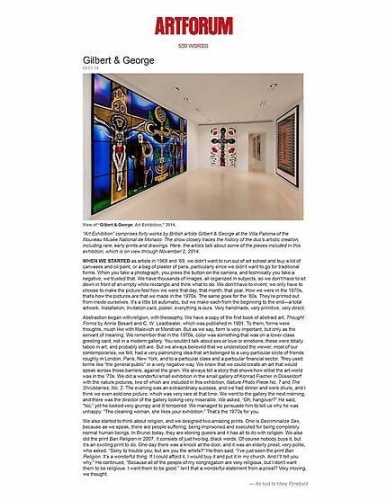

“Art Exhibition” comprises forty works by British artists Gilbert & George at the Villa Paloma of the Nouveau Musée National de Monaco. The show closely traces the history of the duo’s artistic creation, including rare, early prints and drawings. Here, the artists talk about some of the pieces included in this exhibition, which is on view through November 2, 2014.

-- As told to Mary Rinebold

When we started as artists in 1968 and ’69, we didn’t want to run out of art school and buy a lot of canvases and oil paint, or a bag of plaster of paris, particularly since we didn’t want to go for traditional forms. When you take a photograph, you press the button on the camera, and technically you take a negative; we trusted that. We have thousands of images, all organized in subjects, so we don’t have to sit down in front of an empty white rectangle and think what to do. We don’t have to invent; we only have to choose to make the picture feel how we were that day, that month, that year. How we were in the 1970s, that’s how the pictures are that we made in the 1970s. The same goes for the ’80s. They’re printed out from inside ourselves. It’s a little bit automatic, but we make each from the beginning to the end—a total artwork. Installation, invitation card, poster, everything is ours. Very handmade, very primitive, very direct.

Abstraction began with religion, with theosophy. We have a copy of the first book of abstract art, Thought Forms by Annie Besant and C. W. Leadbeater, which was published in 1901. To them, forms were thoughts, much like with Malevich or Mondrian. But as we say, form is very important, but only as the servant of meaning. We remember that in the 1970s, color was something that was on a lower-class greeting card, not in a modern gallery. You couldn’t talk about sex or love or emotions; these were totally taboo in art, and probably still are. But we always believed that we understood the viewer; most of our contemporaries, we felt, had a very patronizing idea that art belonged to a very particular circle of friends roughly in London, Paris, New York, and to a particular class and a particular financial sector. They used terms like “the general public” in a very negative way. We knew that we could create an art that would speak across those barriers, against the grain. We always tell a story that shows how elitist the art world was in the ’70s. We did a wonderful small exhibition in the small gallery of Konrad Fischer in Düsseldorf with the nature pictures, two of which are included in this exhibition, Nature Photo Piece No. 7 and The Shrubberies, No. 2. The evening was an extraordinary success, and we had dinner and were drunk, and I think we even sold one picture, which was very rare at that time. We went to the gallery the next morning, and there was the director of the gallery looking very miserable. We asked, “Oh, hangover?” He said, “No,” yet he looked very grumpy and ill tempered. We managed to persuade him to tell us why he was unhappy. “The cleaning woman, she likes your exhibition.” That’s the 1970s for you.

We also started to think about religion, and we designed two amazing prints. One is Decriminalize Sex, because as we speak, there are people suffering, being imprisoned and executed for being completely normal human beings. In Brunei today, they are stoning queers and it has all to do with religion. We also did the print Ban Religion in 2007. It consists of just two big, black words. Of course nobody buys it, but it’s an exciting print to do. One day there was a knock at the door, and it was an elderly priest, very polite, who asked, “Sorry to trouble you, but are you the artists?” He then said, “I’ve just seen the print Ban Religion. It’s a wonderful thing. If I could afford it, I would buy it and put it in my church. And I’ll tell you why.” He continued, “Because all of the people of my congregation are very religious, but I don’t want them to be religious. I want them to be good.” Isn’t that a wonderful statement from a priest? Very moving, we thought.