Gilbert and George are a two-headed monster. Interviewing them is like being on a British comedy show: They talk at once, crack jokes, and finish each other’s sentences. It’s a polished act.

Born Gilbert Proesch (1943) and George Passmore (1942), and inseparable for the past 45 years in life and art alike, they are arguably the most prolific and famous art duo of all time. For more than four decades they have been making provocative and iconographic work, at once highly personal and political, which has attracted endless praise and controversy. Using themselves as the main subject of their work, they have become an odd fixture of the art world and one of the biggest British art exports ever.

Known for their bold statements as much as for their mannequin-like public personas, they formulated their core principles in a 1969 manifesto, “The Laws of Sculptors”:

1. Always be smartly dressed, well groomed relaxed and friendly polite and in complete control.

2. Make the world to believe in you and to pay heavily for this privilege.

3. Never worry assess, discuss or criticize but remain quiet respectful and calm.

4. The lord chisels still, so don’t leave your bench for long.

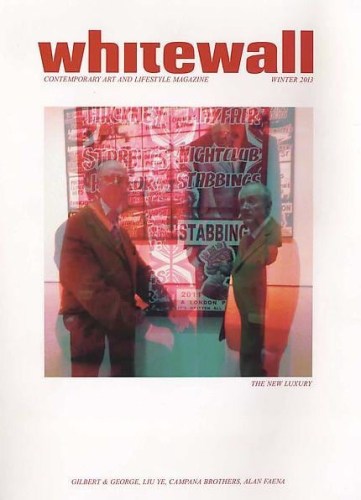

I met the two at the London White Cube gallery shortly after the unveiling of their latest monumental project, entitled London Pictures, consisting of 292 pieces — the largest body of work created by the artists to date. Made of nearly 4,000 newspaper headline posters, which the old rascals claim to have stolen over a number of years, according to the press release, it’s an “epic survey of modern life in all its volatility, tragedy, absurdity and routine violence.” It was, perhaps, the most entertaining and unusual interview I’ve ever conducted.

WHITEWALL: Let’s start with a trivial question: Why Gilbert and George and not George and Gilbert?

GEORGE: When we started first we used to alternate, Gilbert and George, George and Gilbert . . .

GILBERT: Then we settled on this one, like a slogan, not for any reason.

WW: And were you always using only your first names?

GILBERT: Yes, from the first day, for the past 45 years.

GEORGE: Like Van Gogh, who would sign “Vincent.”

WW: I hear that you’re listed in the phone book.

GEORGE: Of course!

GILBERT: The number is still the same; it hasn’t changed since the early seventies. We used to put our address and telephone number in every artwork . . .

GEORGE: . . . because we were unknown and we wanted to be known so people could contact us. But nobody ever did. Nobody ever telephoned from the art.

WW: A friend of mine said he once called, but there was an answering machine . . .

GEORGE: Yes, we do have an answering machine, but the number is the same.

WW: You were the first major western artists to have a museum show in the Soviet Union and China. I remember seeing you work as a teenager at the Moscow Central House of Artists back in 1990. It was a phenomenal, overwhelming experience — the scale, the colors, the bursting energy and sexuality. There was nothing like this ever seen before in Russia. What was your most vivid impression from that visit?

GEORGE: It was a huge show.

GILBERT: We paid for the whole thing. I remember the boy who was doing nailing up . . .

GEORGE: There was this whole team of students hanging the show and when they were having their breaks, there was one rather nice, very studious boy. He was learning English playing cards or something and he showed us his translation book. And basic sentence that you translate in England would be, “Please pass the marmalade.” And the Russian one was “When I grow up I want to be a part of the secret service.”

GILBERT: The English would never dare! “Please pass the marmalade!”

GEORGE: So obvious . . . And the other impression was extraordinary. A private viewing was at seven o’clock, but nobody was allowed in. There was a barrier and all these people trying to get in. We asked what was happening and they said, “Just wait.” And we waited and waited and these two guards came in dress uniform — the army uniform you wear to a regimental dinner, a better, deluxe quality. They looked amazing, very tall and good-looking, they walked through the exhibition all the way and came out and then people were allowed in.

WW: Were they the KGB?

GEORGE: Yes, and they had the most elaborate uniform!

GILBERT: We censored our show ourselves before going there.

GEORGE: Deliberately!

GILBERT: Because if we haven’t done that, the show wouldn’t happen.

WW: You’ve always put yourselves in the center of your work and there’s a strong performance element in your practice. Has it changed throughout the years?

GEORGE: We never said “performance.” We believe these are pictures not by picture-makers but “living sculptures.”

GILBERT: We are the center of our art, so what we leave behind is all us speaking to the viewer, you see always us part of being here. It was not a performance, but a kind of sculpture, a living sculpture, and for us this is a very good form to speak.

GEORGE: If the young people go to college and learn how to make pictures, they should learn how to make these ones. They’re letters, visual letters . . .

GILBERT: We always say we make a kind of moralogue: good people, bad people, what should be changed, sexuality, unhappiness, drunkenness, religion, politics — all included, all what’s inside human beings, not the abstract art that doesn’t offend anybody.

GEORGE: We believe that people who see our exhibitions become slightly different from those who don’t see, unavoidably.

GILBERT: When we started out, it was all about concept art — Minimalist, no emotions, not too much color, no sex . . . It was totally alien to what we were doing, we did always the opposite: too much color, too much sex, too much drunkenness. So it is very human art, more down to earth, like human beings are, not someone who is superior . . .

GEORGE: Thirty years ago when we did pictures with Christ or sex or nakedness, the art world thought we were fucking crazy. That’s been sorted out. Today these are the biggest issues in the world.

GILBERT: Every newspaper talks about gay marriage nonstop . . .

WW: Which leads me to the next question. You recently got married — was it a symbolic act or something more pragmatic?

GILBERT: Quite pragmatic.

GEORGE: Practical. We didn’t want to pretend straight marriage. If one of us fell under a bus tomorrow, it would be a disaster because by law the estate would go to some distant relative, we would lose control . . . not that anyone is dying.

GILBERT: We have a foundation, and by law everything would go back to my family, so that’s why it was very important.

GEORGE: When that happened, a lot of journalists from France were very interested. A lady journalist asked, “What do you think about the gay marriage?” And I said, “Why, are you thinking of marrying a poof?” [Laughter]

GILBERT: There was a very good piece in The Independent about that recently.

GEORGE: The Independent would love to attack the bishops, but they’re limited by law. But if somebody else attacks them, then it’s okay. So we said two or three things about gay marriage. Maybe more gay people would like to be married in the church just as a revenge on these bigots. But, rather, why would you want to get married in church by a bunch of pedophiles?

We have a very good quote on that from Russia. There was a lady working at one of the commercial galleries, and she asked one of the organizers if homosexuality was legal in Russia. And he said, “Yes, in prison!”

GILBERT: Our motto is: Sex is sex, we don’t want to know what it is. George always says when you ask for the meat in a restaurant you don’t ask for a boy or girl meat! [laughter]

WW: Conservative business attire is a big part of your image and reputation. How did you invent that look and first start using it?

GEORGE: Very simple. We are both war babies, we both came out of a wrecked land. I was bombed out of my city. Many people had a leg or arm missing; many buildings were damaged. And everybody knew one thing: Life is going to get better. We felt that we were poor people and if it’s an important occasion, if you try to get a job or if go to a wedding or funeral, you dress up nicely. You try to be polite to get on with life, and we settled for that. We didn’t want to be artists their mothers would be ashamed of. It didn’t work out exactly like that . . .

GILBERT: We went to all the galleries to sell ourselves in ’68 and ’69 and we were promoting ourselves with the idea of being a living sculpture. If you want something, we’ll really do something — a performance, or we’ll write a story or arrange a dinner for you, all these ideas. And we only had one suit on and that’s it.

GEORGE: We realized that a lot of artists dressed in an eccentric way or had eccentric style to show that they were artists. We felt that alienated 90 percent of the world’s population. You can’t get into a restaurant — why be deliberately weird? We wanted to be normal, normal weird . . .

GILBERT: . . . so normal that we became strange!

GEORGE: Outside of the art world we are completely normal . . .

GILBERT: . . . but at the same time everyone recognizes us when we walk the streets of London, everybody knows us, because it’s strange. It doesn’t fit in.

GEORGE: Normal and weird at the same time — that’s the secret. To have both that frees up the brain and you are different, you have space to be creative. Your life is enhanced, like when you’re sexually attracted to someone, everything is different — sky looks different, food tastes good, your whole life is affected by being in love, the difference between a haircut and a shave or having a haircut and a shave by the barber you have a crush on. It’s different. It’s more alive!

WW: So you started out with one business suit for all occasions. How many suits do you have in your wardrobe now?

GILBERT: It depends. We were running out of suits because our tailors were dying. Now we have a new one, but it takes six to eight months to do a suit.

GEORGE: He’s very old-fashioned and he does it all. Most tailors send out the trousers and the buttons. And he does every single thing.

WW: Would you mention his name?

GEORGE: No, because we would never get out suits! We don’t want to bring him more customers. [laughter]

GILBERT: His label says Nicholas of London [shows the label].

GEORGE: He’s an old Greek separatist, very charming.

GILBERT: We never wanted a perfect tailor to make our suits, like one of those Savile Row tailors. Our street where we live in London used to be the most famous street for Jewish tailors. We have Mr. Lustik, Mr. Liberberg, Mr. Chapman — all next door.

GEORGE: When our last tailor retired, we were amazed because they had two sons who were 23 or something, and I said, “You had a business for more than a hundred years. Why didn’t your sons take this fantastic profitable business?” They asked, “What do you call the son of Jewish tailor?” I said, “I don’t know.” He said, “A brain surgeon!” [Laughter]

WW: Describe your collaboration. Who’s responsible for what, and do you ever argue when you make art?

GEORGE: It’s not a collaboration. Yes, we are two people, but one artist.

GILBERT: Because we are always together when we work, so the images, the ideas come. We don’t know exactly when they come and how they come — they invent themselves without us being involved.

WW: Would you call it the third mind?

GILBERT: Yes, the spirit between us.

GEORGE: You could say that. We try to make the pictures to make themselves as near as possible, so that if you could photograph what’s inside you today and take it out and there it was. That’s what we’re trying to do. To lift the pictures out from inside ourselves and trust them, whether they are good or bad. That’s it.

GILBERT: We try to eliminate the artistic hand. Even from the beginning, we always cut off the hand — we don’t want that technique. We want this magic from the brain on the wall.

GEORGE: Mental pictures, yeah? We did these charcoal-on-paper sculptures for some years, big drawings that we folded up. They were taken from copied photographic images because we didn’t know how to make a big one. And people loved the paper and the edges of the paper and the scratching of the charcoal, and we hated it, so we stopped. They were only loving them for the form, not the meaning. They couldn’t get through the meaning because they loved the form so much.

GILBERT: They were too stuck on he technique of art, because art means having a brush in your hand. And we tried to eliminate that. To make what you call “big artworks” after the negatives was a big struggle. It was not accepted back in the seventies.

GEORGE: Museums wanted you to go down to the photography department with collections of Cecil Beaton, not to the fine art department. That was another battle.

GILBERT: We became the first to make what you call visual art. If not, it was just photography. And we managed to re-create it in a form that becomes art. Then we tried to make a big picture off the negatives, but we didn’t know how to protect them. You cannot have a big sheet of glass like that — it’s too heavy — so we decided to make it in panels already in 1971 to ’72.

WW: That’s when your signature grid technique was developed, something that can be easily reassembled?

GILBERT: Yeah, then you can put in a box. It was a practical way of protecting our artwork.

GEORGE: It was so simple: We could take the images in a pile like that and telephone in advance and order 50 sheets of Plexiglas. Then we had this black old-fashioned tape, and stick it up. And we could afford to do that.

WW: Has the process changed over the years?

GILBERT: Now we have big boxes like that [pointing at a giant crate standing nearby in the back of the gallery], where the whole piece goes in, on wheels. Now it’s all one piece, but they are still made of sections.

Like a modern building, they’re all made of panels, bricks and glass . . .

GEORGE: Like life itself — our whole lives are divided into years, months, weeks, days . . .

GILBERT: It’s the composition that is already there. We’re restricted, we’re not able to do everything because we have the grid — we have to keep that. But every moment each composition is different.

WW: How do you edit your work?

GEORGE: In ’69 we wrote a manifesto called “The Laws of Sculptors,” and one of the laws was never discuss or criticize. We accept every picture that comes out from ourselves. Because if we say this is not a good one, maybe we’d be wrong. Why should we be an expert about our own art? If you start to discuss, the end of the world comes very fast!

GILBERT: For us it’s very simple: We have a vision, we keep that vision and it’s so important. The little details have to be toward the big picture, they aren’t important, as long as it fits into the big image.

GEORGE: We fondly imagine that we have an idea what picture the world requires. So we are not doing the pictures that we like, but we think roughly what the world needs, and we do that.

GILBERT: We were always at the edge . . .

GEORGE: We were always wrong. The right thing to do would be to leave art school and split up immediately, because you can’t have two people as one artist, then run and buy canvases. We didn’t do that. Do it wrong and you get it right!

GILBERT: We did too much color, too much alcohol, and we were talking about sexuality, talking against religion. We did a big show called “Was Jesus Heterosexual?” Then, in 1982 to ’83, we did a series with all these boys and all the newspapers said “prostitutes!”

GEORGE: It would be very simple to get it right if we just did girls, but we did it wrong again!

WW: Let’s talk about the work you did in the eighties. The big aspect of it was the glorification of the working class and what would be perceived as “rough trade.”

GEORGE: We always say we only use people as humanity. We realized that in London, unlike many cities, there was no class aspect to a young person. It could be a son of the ambassador or a son of a worker, you couldn’t tell the difference.

GILBERT: It had to be a person who didn’t fit in. We didn’t want a punk, we didn’t want a lower-class person; we wanted some kind of anonymous, ordinary person that looked eternal, forever, everyman. And they are if you look at them.

GEORGE: Nobody could say whether they were rented or not rented, anyway. Impossible to tell! But all the media immediately said, “Rent, rent, rent!” They have a middle-class fear that their sons will go on the game or be queer. So they see these boys and go “Ahhh!”

WW: You went from one extreme of being completely “normal” to being totally exhibitionist and taking all your business attire off.

GILBERT: In ’94 we had our “Naked Shit Pictures” show at the South London Art Gallery very near here, in Peckham. It was a beautiful 19th-century gallery but totally unknown and empty, one or two visitors a day. When we asked if they would do this show, they were terrified and wanted to take some pieces off, but we pursued to have them all. It was amazing success, nearly a thousand people a day down there!

GEORGE: People were actually flying in from every bloody country!

GILBERT: We sold 6,000 catalogues.

GEORGE: There was a lot of hostility from the media, not from the public.

Gilbert: There’s always hostility from the media, still!

WW: They say there’s nothing better than bad publicity!

GILBERT: To publicize our shows is very important. We don’t want this gallery empty of people. That’s why we do the publicity — as much as we can!

WW: Let’s talk about the Warholian aspect of your work. What’s your take on Warhol and Pop art?

GEORGE: Pop art celebrates consumerism, and we celebrate humanism.

GILBERT: It’s a very different philosophy, in a big way.

GEORGE: Pop art doesn’t have the capability to engage the general public that we have. We prefer to be devoted to that which is discriminated against or that which is unloved. We like the chewing gum and vomit on the street, not the famous film stars. Whatever people think is disgusting, we like that. That’s why we used the pubic lice in some of our pictures. They’re huge, as big as our heads, because we realized that nobody has a good word to say for pubic lice. Head lice is okay, parents would discuss head lice on their children on the Tube, but nobody mentions pubic lice. They’ve never been in a museum or in a gallery, so let’s give them a chance, make them happy for once! People asked, “Where did you get them from?” We said, “The same place you got yours!” [Laughter]

WW: How many people are involved in the production of your works?

GILBERT: Only one helper, who’s helping technically.

GEORGE: One boy who followed us back from Shanghai.

GILBERT: We have a company who does the framing and mounting after we’re finished. But making the art is done by us alone in the room, every artwork, every manipulation, every decision — the heads, the suits, the eyes, the background . . .

GEORGE: That’s very important for us because we want to be ourselves. And that’s why we never accepted a commission.

WW: Considering your phenomenal productivity and output, I was expecting to hear that you have an army of assistants and staff of people working for you!

GEORGE: We couldn’t do that mentally. You have to care for the other people and then our brain is gone!

GILBERT: We are very organized. We’re so organized that we’re able to know exactly what we want and how to do it.

WW: When did you did you switch from analog to digital and what do you miss most from your old process?

GEORGE: Ten years ago, back in 2002. Young people thought we used a computer long before we did.

GILBERT: Back then the computers weren’t powerful enough. It would take 15 minutes for a big file to load.

GEORGE: The only thing we miss is the rubber gloves. The language is the same . . .

GILBERT: Every detail is the same: the mask, the color, the black and white, the manipulation in the darkroom — there’s nothing different. That’s why you don’t see the transition over to it.

WW: Queen Elizabeth II is very present in your new series and she’s got many different profiles.

GILBERT: It’s like the seal of approval!

GEORGE: There are six different profiles and all from different coins. We say, “No two queens are alike.” [Laughter]

GILBERT: Every image was taken six times, to give it a different lighting. If you turn a coin, you create different shadows. So that’s what we did. They are all different, every one of them.

WW: What’s your take on the role of monarchy?

GILBERT: Oh, very good! You see Prince Harry in all the newspapers.

GEORGE: A very successful tour, extraordinary!

GILBERT: We like the royal family because it’s so artificial, beyond politics and everything else. It’s untouchable like the Holy Goat. If not, they have presidents like in Germany and they all misbehave and they have to be sacked. But this goes back to such a big tradition of 2,000 years!

GEORGE: Constitutional monarchy is quite an intellectual idea — that you don’t have to think who to have, just the next in line. And with Harry, that’s quite amazing! All over the world there are thousands of girls looking for red-headed boyfriends! They all want a ginger boy, and they’re right!

WW: Yes, it seems like the royal family has been doing a very good PR lately. So you think it’s here to stay, the monarchy?

GILBERT: Oh yes, it is so big now, much bigger than ever!

GEORGE: We were in Germany when the royal wedding took place and a German said to us, “Pity we don’t have any kings here, we could do such a good promotion for Germany!” I said, “Don’t worry — you don’t have any kings, but you still have quite a few queens there!” [Laughter]

WW: What are you political preferences? Who did you vote for in the last elections?

GILBERT: I never vote. George is a conservative.

WW: So you vote Tory?

GEORGE: Of course, it is the most normal thing to vote! We don’t understand why in the creative world, where individualism and originality are supposed to be a very important thing, they all have the same political opinion! It’s strange!

GILBERT: It’s very simple: Art is based on capitalism. Art in some ways is for the rich, no? The poor cannot buy art . . .

GEORGE: But they can look!

GILBERT: It’s capitalism, free-market economy we believe in. We don’t want to be a part of socialism, when everybody has to have the same amount of money. We want free market: We make it, we try to sell it, that’s it! And if not, we do it differently. We try to make a living out of what we’re doing. We always did that. We never borrowed a penny, we never got money from other people, all’s based on free market economy, and that’s the evolution for us.

GEORGE: We remember the days when the artist could go to commercial galleries to see the expensive art of foreign artists, the American art, but they could never say, “I’m an artist” in England.

GILBERT: That only came about after ’84, when Thatcher came to power and the art world changed because of free market. You were allowed to do export/import, whatever you want. Before you weren’t even allowed to export or import money.

GEORGE: You had to have it written down on the back page of your passport if you took 200 pounds to France. The young artists don’t realize that they came out of Thatcher and they hate Mrs. Thatcher. But she made them, in fact!

GILBERT: She made them rich!

WW: Some people say Tories are not good for the young artists, education. They did cut down on art funding and education.

GILBERT: The evil Tories!

GEORGE: Strangely enough, in private most people in fine art say that Tories are very good for art, but they wouldn’t say that in public! There have never been more galleries and more people making a living out of art, especially in England. This doesn’t exist anywhere else in the world.

GILBERT: London became one of the biggest capitals of art, nearly bigger than New York — so many galleries, so much art! Even all the newspapers are full of articles about art, they all have pages and pages of art that you don’t have in any other country. The art section of the New York Times is very small compared to British newspapers. The British art world became a monster!

GEORGE: London blossomed!

WW: You were representing England at some important international shows . . .

GEORGE: By mistake!

WW: What was the point when you realized that you made it mainstream?

GILBERT: We never believed that!

GEORGE: We still think that we’re getting there. We are not part of the establishment. We have so many enemies out there, not in the public but in the official world.

GILBERT: . . . so many art critics!

GEORGE: Unbelievable!

GILBERT: Us and them! They’re the enemy — they ought to be!

WW: Who are your peers in the contemporary art scene?

GEORGE: We support all the art because all the artists are doing something different. But we’re not followers of art; we’re not gallerygoers.

GILBERT: As an artist, I don’t want to be a part of it. We want to make new art in front of naked world. We want to be influenced by the world, not by art. You have to have a philosophy . . .

GEORGE: Tell the truth and chain the devil!

GILBERT: I don’t want artists at our dinners. You know why? You know what is written here? [Points at his forehead] Jealousy! And that’s very big in the art world.

GEORGE: Art dealers are very generous as well!

GILBERT: That’s why we were quite happy that Thaddeus Ropac, our French dealer, didn’t come to the opening. Jealousy!

GEORGE: It could only make him unhappy . . .

WW: As artists who turned your entire life into a spectacle, do you have plans for your death?

GILBERT: We have a foundation that only kicks in when we’re dead. It’ll have all the studios, archives, drawings, press . . . It’s like a small museum. We don’t want a big museum, we want something human — a human house where we lived.

WW: Would you make a spectacle out of your death?

GEORGE: No, we wouldn’t do that! Maybe soon nobody is going to die, with all the technology and medical advances? When I was a child we never thought most people would live to be 90 or 95. It’s a new idea.

GILBERT: We just want to be buried in our backyard or the small cemetery near us.

GEORGE: It’s a very special cemetery for nonconformists who didn’t belong to the Church of England. There are three famous tombs: One is William Blake, another John Bunyan, one of the pilgrims, and the other Daniel Dafoe. They’re all famous writers, but only one gets flowers all the time, William Blake.