Interview with Billy Childish

By: José da Silva

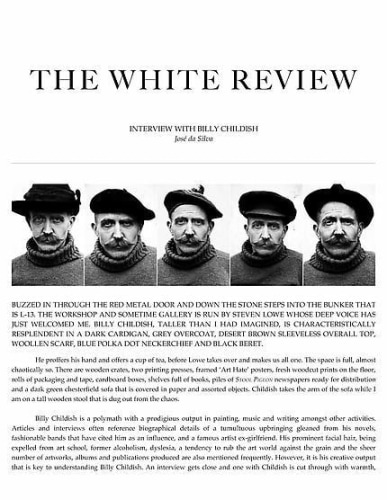

Buzzed in through the red metal door and down the stone steps into the bunker that is L-13. The workshop and sometime gallery is run by Steven Lowe whose deep voice has just welcomed me. Billy Childish, taller than I had imagined, is characteristically resplendent in a dark cardigan, grey overcoat, desert brown sleeveless overall top, woolen scarf, blue polka dot neckerchief and black beret.

He proffers his hand and offers a cup of tea, before Lowe takes over and makes us all one. The space is full, almost chaotically so. There are wooden crates, two printing presses, framed ‘Art Hate’ posters, fresh woodcut prints on the floor, rolls of packaging and tape, cardboard boxes, shelves full of books, piles of Stool Pigeon newspapers ready for distribution and a dark green chesterfield sofa that is covered in paper and assorted objects. Childish takes the arm of the sofa while I am on a tall wooden stool that is dug out from the chaos.

Billy Childish is a polymath with a prodigious output in painting, music and writing amongst other activities. Articles and interviews often reference biographical details of a tumultuous upbringing gleaned from his novels, fashionable bands that have cited him as an influence, and a famous artist ex-girlfriend. His prominent facial hair, being expelled from art school, former alcoholism, dyslexia, a tendency to rub the art world against the grain and the sheer number of artworks, albums and publications produced are also mentioned frequently. However, it is his creative output that is key to understanding Billy Childish. An interview gets close and one with Childish is cut through with warmth, humour and an oddly self-aware narcissism. He speaks with a Kentish accent, a slightly softened mid-century London working-class inflection that has crept south.

THE WHITE REVIEW — I think it’s recording…There we go.

BILLY CHILDISH — Get that important information in.

THE WHITE REVIEW — I read an article that said that if you recognised 20 per cent of what was written about you in an interview then it was a good one. Why do you think that in the majority of cases the Billy Childish in the article is almost unrecognisable to you?

BILLY CHILDISH — I’d imagine I am not alone in that. That’s what goes on with history as well – when things are transcribed they are bent out of shape. It is possible that I have a bit more of a problem because I tend to procrastinate and talk in circles and make strange detours. I really like contradiction – or embodying contradictions – embracing them into one truth. I’ve also got a very strong sense of humour, which is most often left out of articles. Then I get asked a lot of questions about things I’m not even that interested in and I’m somebody with an opinion on nearly everything. So I answer and the reader presumes that people with strong opinions are actually worried about the thing that they’ve been asked about. But they are wrong. I’m not generally worried about much.

THE WHITE REVIEW — Do you think you come across better when you’re filmed or recorded? There’s intonation in the voice…

BILLY CHILDISH — Possibly, you’d see that I thought most of the questions and situations were funny. Maybe. I’m not that bothered about being interviewed or about talking about these things anyway which is the other odd fact.

THE WHITE REVIEW — You seem to get asked a lot.

BILLY CHILDISH — Yes, and generally I think, OK I did say that and they did get the gist of my meaning. As far as reviews go I don’t like someone liking or disliking something for reasons that have nothing to do with me. I expect the person to have some intelligence and see around the thing. Journalism and criticism? Exhales clicking his tongue and shaking head] Kurt Schwitters is my favourite Dadaist: a great sense of humour…

THE WHITE REVIEW — You have a tattoo of Schwitters’ poetry, is that right?

BILLY CHILDISH — That’s right, a tattoo of one of his London poems on my left buttock. I got it when I was a punk rocker because we used to have to go through all sorts of rigmarole getting into foreign countries in those days. They ask for distinguishing marks on your passport and I wanted to have ‘tattoo on left-buttock’. So I thought I’d go for a Kurt Schwitters poem. Anyway, Schwitters said, ‘The artist creates, the critic bleats.’ He had a huge sense of humour and was not pious and up his own arse like a lot of those other Dadaists and our modern artists.

THE WHITE REVIEW — The original Dada was, of course, cut through with humour the whole way.

BILLY CHILDISH — Absolutely. He’s post-Dadaist. He was middle-class and they didn’t like him, because they were getting political and they saw him as middle class. But Kurt Schwitters maintained a huge amount of humoristic integrity and great endeavour in his work. He was a master of the light touch. He was the real deal.

THE WHITE REVIEW — He is someone who has cropped up a lot in previous interviews you have done.

BILLY CHILDISH — Yes, and unfortunately, of course, even the Tate can have exhibitions of Schwitters. They like to align themselves with real things as well as faux. And actually a Kurt Schwitters exhibition can be quite tiresome. I saw a massive one when we were playing in Paris, at that Pompidou Centre. It was just ridiculous: it went on room after room. Too much is too much.

THE WHITE REVIEW — Did you see the Dada exhibition at the Pompidou in 2005?

BILLY CHILDISH — No, I saw the Dada exhibition at Southbank in spring ’78. I’ve only seen a handful of exhibitions. I think that museums and galleries tend to destroy art. The environment is very unsympathetic. They look like fucking airports and include a lot of things that definitely shouldn’t be included.

THE WHITE REVIEW — What kind of things?

BILLY CHILDISH — Dada exhibitions! Laughs]. My wife was rather keen on seeing the Frida Kahlo exhibition and I’d seen Frida Kahlo’s things in books before and I thought I’d quite like to go. But it was overpriced to get in and very badly laid out, huge crowds, slogans on the wall telling you what to think: describing what you’re looking at all the time. And Frida is just not that good. I mean, there were some lovely little drawings at the beginning, from when she was just starting out. Frida Kahlo is actually OK. But it’s not OK if you jam it all into a gallery. It just doesn’t translate, especially into a modern white-walled gallery. If it was done in a tasteful building or in someone’s front room I’m sure it would be far more engaging. The art galleries of today are set up for art tourism.

THE WHITE REVIEW — Do you think it’s more than just the physical building?

BILLY CHILDISH — Yes, it’s the will of the people. It’s a big problem when things become very egalitarian and open, and are worse off for it. A library or a gallery should be empty to a degree. It should have elbow room. It should have calmness. It should be a statement about who we are, not a statement about populist culture. Real culture isn’t very popular. Real art isn’t that popular. These would be my arguments with places like the Tate when they say they are bringing challenging work to ordinary people. If it was challenging the place would be empty. If you challenge people they get the hump and clear off. The Tate is populist: it’s a day out. That’s not necessarily bad, but we’ve already got places for a day out. You don’t have to make everything into a fucking knees-up.

THE WHITE REVIEW — You have often been referred to as an outsider but you have said that this label is a bit patronising, that instead you’re the ultimate insider. Do you think living outside of London, living in a provincial town has affected the way you are percieved?

BILLY CHILDISH — Possibly, but my contention is that London and major cities are the most provincial places on earth because they’re full of provincials trying to make out that they’re not provincial. For years and years we came to London every week to play music and I’d always deplored Londoners because they had no sense of humour and worried about everything. Then we had a Londoner join our group, ‘You’ve never met any Londoners,’ he said. ‘These po-faced bastards aren’t from London! Laughing] These people have come from the provinces desperate to appear not provincial.’ In a way major cities are magnets for the provincial and the worldly people stay in the provinces. Or some of us do.

Critics want you to get in your box and shut up. That’s why they don’t like it that I’m a writer, musician and painter. That’s totally unacceptable to their small minds. Also this means that I’m not beholden to any one of the groups that I belong to. And that means that I might say things that they don’t want me to say.‘If you’re not one of us, exclusively, that means you smell and you’re not our friend.’ So you’re back into the politics of the playground… I just say, ‘No to the label of artist, musician or writer. I do not accept that any of these groups of people have the authority to validate, or invalidate me. I validate myself and… and this actually causes an even bigger problem.’ Laughs]

You’re really meant to be contained by your friends and your peer group, as well as the discipline that you work in. If you’re in the art club or the music club, that means you won’t say, ‘Look, actually all this is a load of fucking baloney!’ They’re all bigging it up because they want their jobs and status. They’re making out that their job is difficult and highly evolved when it isn’t. Artists aren’t special, in fact they are definitely not special. But if you work in an office and say ‘Look, I can do all this work that takes you two weeks in two hours. Can I spend the rest of the week at home?’ Ooohh. You’ll be an outsider fast. But of course you’re not an outsider, you’re being bright and intelligent. What is actually happening is you’re not being dumb and provincial enough.

THE WHITE REVIEW — Do you think that your life and work follow a strong intertwined biographical narrative?

BILLY CHILDISH — I think in some ways it’s an anxiety that enables me to have that capacity. It’s something I’d prefer to let go of. I’m looking for freedom from being categorised or identified with aspects of myself. But at the same time I use this very strong biographical information to negotiate a world – a world which I find quite mental, by the way. So I still refuse to identify myself as Billy Childish the artist, painter, writer or musician, because in my estimation only an idiot would want to be something.

THE WHITE REVIEW — Do you thing think the blurring between the fictional and biographical is a big part of your work and your persona?

BILLY CHILDISH — To a degree. I accentuate the fictional element of my writing when being interviewed because I have had people telling me that my novels were purely autobiographical. And this is an incredible thing. I’ve said are you prepared to go and strip all the novels in the library then? Because most of that’s fact. It’s about stuff that happened to those writers. I am going to write this biography and call it fiction because I say it’s fiction. Because all biography is fiction. Who’d call Knut Hamsun’s Hunger a biography? But it is, because he lived that. But he puts it through the filter of prose and poetry. That’s what fucking fiction is! Of course, the great joke is that you get people who write autobiographies and they’re the real great works of fiction. My novels are more honest and have fewer lies in them than autobiographies. But they are fiction and that’s my nature.

THE WHITE REVIEW — Is that tag put on you because you are Billy Childish? For example in the text accompanying your ICA exhibition a couple of years ago it says that your ‘prodigious range of activities can best be understood as a total work of art – one which centres on your] own persona.’ Do you think that the exhibition would have been different if it was just your paintings? It had a lot of your record covers and it showed you as a kind of ‘total artist’.

BILLY CHILDISH — That’s the kind of thing they were going towards. I don’t know. Well, I’m a weirdo because I’ve done so much music and so much writing and so much painting and then they know that this upsets the art world and the music world – Look, I’ll show you what I mean. I wrote this Pulls out a passport sized light-brown notebook from his inside jacket pocket; opening it, the scribbled writing is thick green pencil and almost illegible] this morning on the train. I’ve always been trying to deal with this thing. I’m working on a new book of poetry. This is called ‘art cunt’:

and the art cunts used to have it that im a poet not a painter or the art cunts said i was a musician not a painter and the poetry cunts said im a painter not a poet and the musician cunts said i dont know what the cunt is but hes certainly not a musician but now the art cunts say im not a poet or a musician which i presume means that i am now a bona fide art cunt

It’s a bit sweary.

Childish stands up to take a telephone call from his wife. He speaks for a while, rather jovially yet tenderly, before turning to me]

My wife said, ‘I’m sure you’re setting him straight.’

He continues on the phone while playing with his new brass doorknocker shaped like a Sunderland flying boat. When he is finished he hands the phone back to Steven Lowe and as he walks over continues speaking]

I went to the ICA the other day for an opening. My New York gallery represent this feller called Juergen Teller. And I spoke to this Juergen Teller bloke and I said, ‘I thought you were Chinese,’ because it said Juergen Teller: Woo! But the Woo – I’m dyslexic – was something to do with the title of his show, not his name. So when I saw he wasn’t Chinese I was surprised.

At art school I never did Art History. I didn’t go to exhibitions. I stopped seeing music when I was 18, although I played music I didn’t bother going to see shows after ‘78 because punk became boring. Since ‘77 I’ve never tried to be on the scene and I don’t go to parties and I don’t hang out. I don’t read magazines and I’m not that interested in the news or art exhibitions. And of course I’m uneducated, apparently. I left school at 16 and went into the dockyard. So what happens is, I just talk to people at these art things and they ask me about so-and-so, and I say I’ve never heard of him. They say, ‘Yes you have.’ Because I’m totally honest I say if I haven’t heard of this artist or that musician. But they insist I have and that I’m trying to be cool in pretending not to. So I have this battle socially. That’s another reason I don’t do social things.

The simple thing is I don’t pretend to like things or pretend to dislike things. I’m often accused of not liking conceptual work. Well I’m a massive fan of Dada – since I was 17. What I don’t like much is purely commercial Dada. I’m not a tourist. I’m actually interested in what things are. Jimi Hendrix is one of my favourite musicians. I like 30 to 40 per cent of it. I’m not one of these people who likes something and then that means I will take every piece of crap they put out.

THE WHITE REVIEW — You’ve said the same about Munch. You like his later work?

BILLY CHILDISH — Late Munch’s work is probably the height of modernist painting. It’s just incredibly gutsy and brave. I can’t believe how anyone was swallowing that stuff back then. I don’t think they were actually. Munch’s work makes Bacon look like an affected student trying to be weird and dark, like some worried Goth kid. You see Hockney’s woodland scenes compared to Munch’s and they look like they were painted by a constipated eunuch having a cup of tea with his auntie. Munch has sex and life running right through the brush.

THE WHITE REVIEW — These influences you have – Dostoyevsky, John Fante, Charles Bukowski – how did you find out about them if you didn’t have a formal education?

BILLY CHILDISH — I was given up on. My father left when I was 7 and no one bothered with me. I was told I was thick and stupid from the get-go. As it happens my father had aspirations to be an artist and we had art books in the house, so I saw that stuff, although I went to the local secondary modern and was put in remedial classes for backwards kids. Meanwhile my big brother had a Grammar school education. I remember Hunger, by Knut Hamsun, lying on the bathroom stool and eyeing it up. It had a terrible cover, maybe by René Magritte or someone. I didn’t read it. I just remember looking at the cover. It took me five years to decide to read it.

When I was at Saint Martin’s Peter Doig liked my poetry and said, ‘You should read Bukowski. You’ll like it.’ He gave me a dog-eared copy of Erections, Ejaculations, Exhibitions and General Tales of Ordinary Madness, published by City Lights. Now I’m someone who’s really good at following trails. So I read the Bukowski thing and thought this is fantastic. If you like, it gave me permission to write about everything that really happened to me. Then I went and bought everything I could by Charles Bukowski. And Bukowski kept mentioning John Fante, so I think I’ve got to read Fante. And Fante says Hunger is good. I thought, I know that book, that’s at home.

I just follow these trails. So I thought, what happens is when you find out the thing behind the thing, it just gets better and better. And actually, no-one’s climbing a mountain here, this is a big fat plain and certain things stand up like rocks and are always good and relevant. But people are trying to con you that we’re growing and learning and there’s progress, when most often it’s retrograde. Martin Amis or Will Self write like Reader’s Digest when you compare it to the real thing like Dostoyevsky.

When I was at this ICA thing the other day I was introduced to a man called Norman, he was a curator at

the Royal…

THE WHITE REVIEW — Norman Rosenthal?

BILLY CHILDISH — I’ve never heard of Norman Rosenthal. He was quite a nice friendly bloke. He said, ‘So you’re the one and only Billy Childish.’ I said, ‘I presume so.’ And he said, ‘So Billy, tell me, who are your contemporaries, the people that you admire?’ I said: ‘Van Gogh and Dostoyevsky.’ He was like ‘Har!’ and this was brushed aside slightly. I wasn’t trying to be clever. I just thought who are my contemporaries? And automatically chose my friends: Dostoyevsky and Van Gogh. They’re contemporary to me. They’re more contemporary than Martin Amis and Damien Hirst.

It’s not the case that things become relevant or irrelevant, but you’d think if someone landed from Mars and looked at Van Gogh’s work and Dostoyevsky and then they put what we consider contemporary next to it, they’d say ‘Well Dostoyevsky and Van Gogh must be 300 years in the future.’ That’s if we must look for ascendance.

There’s a fantastic bit in The Devils. Dostoyevsky does this great piss-take of somebody who was apparently based on the Russian writer Turgenev. There is a scene at one of these society events that Dostoyevsky’s always sticking in his novels, where they get this writer along to sort of put on a show. And he does this reading about a shipping disaster that he saw in England. Now, I’m only remembering this from about ten years ago. But I think there’s a ship that’s sunk and they’re trying to rescue the crew and passengers. They’re pulling in all these drowned people and there’s chaos. Well, this feller, who represents this Turgenev, is telling this tale, and the narrator, Dostoyevsky, says that what this feller is really saying is, ‘This drama and death is all very exciting, but what’s more interesting and more exciting is me being here telling you about it.’

About the time I read this was 9/11. Two or three days afterwards, I saw a copy of The Guardian and it had a picture of the little second plane going towards the towers and a banner headline proclaiming that the great Martin Amis had written a special piece about the disaster. So I thought, OK, let’s see what Mart’s got to say, especially as I’ve only ever managed to read a paragraph of one of his novels without vomiting. I started reading: Amis talked about this second plane ‘sharking in’ across the Hudson. I remember the term ‘sharking in’. And I thought, this is great because there’s the photo and an imbecile can see that it looks like a minnow, not a shark. But of course Amis wants to say ‘sharking’, so he’s going to say ‘sharking’ no matter what the evidence is, because he’s a great writer. I read all this and I thought this is Dostoyevsky talking about Turgenev. This is a great big disaster, it’s a terrible thing, but what’s much more interesting is Amis talking about it… So what happens is Amis’s ego is trundled out and thinking people are impressed by it, mainly because no-one’s actually looking or thinking at all.

THE WHITE REVIEW — It gets ahead of the truth or what happened…

BILLY CHILDISH — Yeah, but that’s secondary. Even in this interview you get that feeling. I am quite a narcissistic, full-of-myself type of person. It’s a natural thing. You get on your high horse and you think you’re the big I Am, giving out this information. And what needs to happen, you need a split second where you open and you, the self, you, the idiot, is seen. And you rein it in and try to get back to the real deal and try to stop being such a blowhard and get real. But these bastards can’t manage it.

THE WHITE REVIEW — Because it’s difficult?

BILLY CHILDISH — Well it’s difficult and it’s not. Really it’s pretty easy. It’s called humour, but the British lost their sense of humour a while back. Totally understandable but it’s not something to be celebrated. Again, the attention is all on the wrong bit.

THE WHITE REVIEW — It’s on the shark and not on the minnow.

BILLY CHILDISH — Well, it’s not even that. Don’t forget it’s the editor wanting to be close to Martin Amis. People go, Woo! Everyone wants everything to be sexy and something that’s happening and modern and real – contemporary. And there’s nothing as dated as the contemporary.