The Guardian

March 2, 2012

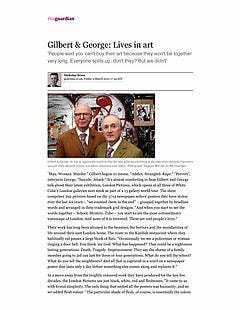

Gilbert & George: Lives in art

By Nicholas Wroe

"Man. Woman. Murder." Gilbert begins to intone. "Addict. Strangled. Rape." "Pervert", interjects George, "Suicide. Attack." It's almost comforting to hear Gilbert and George talk about their latest exhibition, London Pictures, which opens at all three of White Cube's London galleries next week as part of a 13 gallery world tour. The show comprises 292 pictures based on the 3712 newspaper sellers' posters they have stolen over the last six years – "we counted them in the end" – grouped together by headline words and arranged in their trademark grid designs. "And when you start to see the words together – School. Mystery. Tube – you start to see the most extraordinary townscape of London. And none of it is invented. These are real people's lives."

Their work has long been attuned to the beauties, the horrors and the mundanities of life around their east London home. The route to the Kurdish restaurant where they habitually eat passes a large block of flats. "Occasionally we see a policeman or woman ringing a door bell. You think 'my God. What has happened?' That could be a nightmare lasting generations. Death. Tragedy. Imprisonment. They say the shame of a family member going to jail can last for three or four generations. What do you tell the school? What do you tell the neighbours? And all that is captured in a word on a newspaper poster that lasts only a day before something else comes along and replaces it."

In a move away from the brightly coloured work they have produced for the last few decades, the London Pictures use just black, white, red and fleshtones. "It came to us with brutal simplicity. The only thing that united all the posters was humanity, and so we added flesh colour." The particular shade of flesh, of course, is essentially the colour of their flesh and images of the two men lurk behind the texts, as they have appeared in much of their work over the last 45 years.

Their distinctive appearance, subject matter and propensity to situate images of themselves in their art has ensured Gilbert & George are among the few artists to enjoy recognition by the general public. When they venture outside their Spitalfields home they are photographed by the art tourists who haunt the newly gentrified area. There is fan graffiti on the walls opposite their front door. "We are very proud of that," says George. "People say hello. Lorry drivers shout at us. One of those enormous trucks delivering steel once stopped and this middle-aged skinhead shouted out the window, 'Oi. My life is a fucking moment, but your art is an eternity'."

The forms and subjects of this eternal art have been many and various over the years since they first met as students at St Martin's School of Art in 1967. They began as "living sculptures", sometimes their faces covered in metallic paint, singing Flanagan and Allen's music hall classic 'Underneath the Arches'. A 1969 piece of "magazine art" called 'George the Cunt and Gilbert the Shit', gave early indication of their ability to shock as well as pre-empting the potential criticism that might be levelled against them. They made large charcoal drawings – which they nevertheless insisted were sculptures – based on photographs of themselves. They further explored taboo language and images as they moved into films and photography proper through which they probed, with increasing graphic clarity, various subjects found near their east end base such as working-class youth, immigration and homelessness, as well as aspects of themselves including microscopic images of their own blood, semen and faeces, often accompanied by images of themselves in their trademark matching suits, or in varying degrees of undress.

"We have two main privileges," says George. "We can bolt the door of the studio and make pictures that say exactly what we want. Then we can take them out into the world and no one can say, not this one or not that one. You can't shout some of these thoughts on the street. You'd be arrested." "But it is all part of the language of human beings," says Gilbert. "People were told that shit was shocking. Shit is not shocking."

Their work has duly provoked more than its share of both real and sometimes manufactured outrage, and their professed Conservative sympathies have been equally frowned on within the art world. But more often than not they have enjoyed commercial and critical success as well as establishment recognition. They won the Turner Prize in 1986 and represented the UK at the 2005 Venice biennale. The Royal Academy once sought legal advice as to whether it could admit two people for one of its limited memberships. "Every two years they telephone to ask whether we would accept membership," explains George. "We say "Ask us. Write us a letter and we will reply". But they say it doesn't work like that. You have to say you will accept and then they will ask you. Not very honest, is it?"

In 2007 they were the subject of a large Tate Modern retrospective. "We felt we deserved it", says Gilbert. "But we wanted it in the right Tate, not the wrong Tate." When the idea was first proposed they were told that Tate Modern had never shown a British modern artist and had no plans to do so. "Then we knew we were on a journey. We had something to beat. And we won through by slow persuasion. We made it difficult for them to say no, because museum directors hate to say no in case they are proved wrong in the future."

They say they don't believe in the "racial division" of the two Tates. "You can't do art by passport," says George. "Gilbert is from Italy, Lucian was from Germany, Francis Bacon was from Ireland. That is what the modern art world is like here. And they have made a decision on those two buildings that will be forever fucked. A disaster. Show, say, a postcard of a Caro sculpture to anybody you meet in the street and they will say that is modern art not British art. So surely it should be in Tate Modern." "Every English artist who has a show in Tate Britain is finished two weeks later," says Gilbert. "It's the kiss of death. If you have Tate Modern, then the other one must be Tate Old-Fashioned. They're trying to say that they don't really believe in British modern art." It is a subject that has long exercised George. "At my first art colleges, art only came from wine growing countries. Teachers never mentioned an artist from the north. Later you couldn't be an artist unless you were from New York. That felt frightful. In that sense, to say you are English and an artist was a new idea."

This reference to his early art life – he only half-jokingly lists his teenage influences as "Jesus, mother, Van Gogh and Terry-Thomas" – remind us that while G&G was born in 1967, there was a time before Gilbert and George. In fact, George Passmore was born in Plymouth in 1942 and was brought up in Totnes in Devon. He had an absentee father, a larger-than-life mother and an elder brother who was converted to evangelical Christianity by Billy Graham and became a vicar. (Some years later his brother "saved" their missing father when he became a Christian.) George left school at 15 to work in a local bookshop, but took art classes in the evenings at the progressive Dartington Hall School where Lucian Freud had been a student before the war. His facility for drawing and painting prompted an invitation to become a full-time student and the plan was for him to move on to the Bath Academy of Art at Corsham where Howard Hodgkin was a tutor. Corsham rejected him and George left for London where he did various jobs – working in Selfridge's, in a music hall bar, and as a childminder – before enrolling at the art school of Oxford technical College en route to arriving at St Martin's in 1965.

Gilbert Proesch was born in a village in the Dolomites of northern Italy in 1943. He was from a family of village shoemakers and his early art revealed itself through traditional Alpine wood carving. He attended the Wolkenstein Art School in the next valley to his home and then, instead of taking the expected route south to Florence or Venice to continue his art education, went north to the art school at the medieval town of Hallein near Salzburg in Austria before moving on to the Munich Academy of Art where he studied for six years.

"So we are very highly trained," says George. "We did seven or eight years of naked ladies," adds Gilbert. But there was little evidence of their traditional background by the time they met at St Martin's on its renowned sculpture course. "St Martin's was very special because, briefly, it was the most famous art school in the world. And that department in particular. There were TV crews from Venezuela. We felt very arrogant about being there. They made us feel very privileged." But Gilbert and George, along with some fellow students such as Richard Long and Barry Flanagan, reacted against the orthodoxy of the time, characterised best perhaps by Anthony Caro's large abstract works, and an early product of their partnership was a jointly staged diploma show on two tables in a Soho cafe: "But we did give them tea and sandwiches when they got there." Later they photographed themselves holding sculptures before realising that they could remove the sculptures to just leave the human beings. "It was our biggest invention. We had made ourselves the artwork."

The opposition to this strategy included St Martin's writing to a potential sponsor advising having nothing to do with them. "And we felt very proud of that," says George. "We knew we were on our own. It was hard but that's why a two is such a common arrangement. It makes you stronger. People said you can't buy their art because they won't be together very long. Everyone splits up, don't they? But we didn't. It was us against the world in that the only galleries exhibiting at the time were minimal. Figurative was not really allowed. Colour was taboo. Emotions were taboo. It all had to be a circle or a square or a line. And be grey or brown or black or white." "And being in the work ourselves was not liked," adds Gilbert. "That's not the case now, everyone is in their work. But then we two were like a fortress. You become somehow untouchable."

The precise nature of their relationship has long been a source of speculation, given additional spice in the 90s when it emerged that George had been married as a young man and had two children. In 2008 Gilbert & George entered into a civil partnership, but they said at the time this was primarily to do with the practical business of protecting the others interests if one of them were to die. Even their friend, and biographer, the late Daniel Farson concluded by saying in his 1999 study of them that "frankly, I have no idea what goes on".

And far from being gay spokesmen they say they are "just the opposite". They object to their work being described as homo-erotic, claiming it is just "erotic". "Sex is just sex. When you ask for a steak in a restaurant you don't ask whether it is a girl or a boy." That said, they did complain when a critic said that at St Martin's they called themselves living sculptures while "anyone with eyes in their head could see that they were actually two fruity gays in suits". "I phoned the editor, not the writer," says George, "and she said it was meant as a compliment. I said 'Madam, you are a liar. Good day.' But I suppose it is another one of our battles in a way. So why not. We deal with everything."

In 1970 they were invited to show some of their charcoal works in Düsseldorf. "The dealer asked the price and, not thinking for one second that anyone would buy it, we said rather big-headedly, '£1000'. The next day he sold it. We were amazed and had enough money to misbehave for a year." Soon after they performed their singing sculpture in Brussels in a borrowed part of a gallery – "it would be called a pop-up space now" – and were invited, on the spot, to open Ileana Sonnabend's new gallery in New York which resulted in the NYPD having to control the crowds in one of the first downtown art events. By this time they were resident in the Fournier Street home that they have occupied ever since. They say when they bought the first house in 1972 they got a free studio at the back, when later they wanted to expand and bought the studio next door they effectively got a free house.

The change in the neighbourhood has been profound in the intervening 40 years – "We know people who live here and who have never been to Oxford Street. It's just some distant and boring place." – and the transformation of the art world has been equally dramatic. "When we were baby artists, you could ask people on the street to name an artist and they would only mention long dead ones; Michelangelo, Leonardo, Van Gogh. If you asked them to name a living murderer, they'd know two or three in prison. But that has all changed."

They are straightforward in their proselytising beliefs for art in general and theirs in particular. At St Martin's they made a looped tape recording simply saying "come to see a new sculpture" and used marshmallows and cigarettes to entice people. 'We did that because I remember Richard Hamilton coming in and speaking to seven people because no one had told the students. We thought how wretched. We never wanted to make that mistake. At least make sure people know about your work. No one has to go to an art show, but we want them to know that it is there if they did want to go. And if you take an exhibition to a city and 20 or 30,000 people see the show, your work stays with them forever. They become a little bit different than if they hadn't gone to the show."

Gilbert and George and their work have travelled all over the world including trips to China and Russia in the early 90s and most places elsewhere since. "We were recently in Gdansk where just the idea of two men being one artist is still something to get over. There may be a sense in London of people saying 'here they go again', but in other places it feels as pioneering as when we began."

Most of their early photographic work was made in the near derelict kitchen at Fournier Street. "It was very primitive", says Gilbert, "but those pieces are now some of the most expensive ones. And we didn't really know how to do it. It was a new type of art to make work out of negatives and photographs. Back then art meant oil paintings, especially for museums. To make this new work into an art form took years."

They say from the beginning they have had an eye on both posterity and the past. "We don't believe modern is it alone. We have to make an art that will survive into the future, and to prepare our pictures for that. And to take account of the past is essential." Not that they have set foot in a national gallery for years. "We know it all," says Gilbert. "But we want to be inspired by life in front of us and not that sort of brain pollution. A lot of artists go to a gallery and see a picture and then make art. We never did that." "If you have a landscape painting in a museum, people glide past it," says George. "But if there was a little policeman on the horizon and a tramp in the foreground masturbating, then it becomes an amazingly interesting picture. We have thoughts and feelings in our pictures, although that does have a price."

Preparing the vast amount of material that became the London Pictures was a physically demanding task, "but sorting through all those 'man dies' 'woman dies' left us sort of crazed," says George. "As we made these pictures we lived through them. You really began to feel it, all this death. But it is very important that we carry on telling the truth as far as we can work it out. We were making pictures then and we are making them now. It's very simple. How we are tomorrow is how our new pictures will be. But it is always a long journey, which can be exhausting and rewarding. But at the end of it, we know there will come a time when we will find ourselves standing in the middle of White Cube, holding a glass of white wine and being licked all over by teenagers. It's quite a magic moment, and that will be that."