By Holland Cotter

Dynamic duo, gruesome twosome or just plain geeks in ties and tweeds, the British artists Gilbert & George don't seem to care what you call them as long as you pay attention, which you couldn't avoid doing if you tried in their suffocating and disordered wraparound survey at the Brooklyn Museum.

Partners in life and work for 40 years, the artists have had a major career, particularly in Britain, where they were a sensation long before "Sensation," and now hold a kind of national monument status. Their new show at the Brooklyn Museum, "Gilbert & George," originated at Tate Modern in London.

Yet popular is not really the word for them. They're too strange for that. And to perpetually temperature-taking art-world eyes, they have always stood a little outside the coolness loop, a tad beyond the pale, a touch too much.

The look-alike personal style they've affected, a robotic blandness, has probably had something to do with this; they are certainly no one's idea of a glamour couple. And their sleek, photo-based, politically incorrect across-the-spectrum art is as hard to love as it is to categorize. Even if you appreciate it, you may prefer not to spend time with it.

Then there's the perversity factor. They have a funky sense of beauty and an appetite for unsightly things, things most people come to art museums not to see. They were using images of feces back in the 1980s, long before Andres Serrano got the idea. In the 1990s, when they had reached an age at which most exhibitionists put their clothes back on, Gilbert & George, then in their mid-50s, took theirs off. More recently, when the art establishment had declared blatantly topical political art to be anathema, that's what they made.

And they keep making it. It's as if they can't stop. And digital technology has only upped the output, which is one reason the Brooklyn show looks the way it does: oppressively and exhaustingly busy and dense, without even a clarifying logic of chronology to offer relief.

At the same time, for exactly these reasons, the show is a vivid experience. First look may be best look, but it's a memorable look. And it poses a genuine love-it-or-hate-it proposition, something in short supply these days, but one these artists have been offering for years.

Gilbert Proesch (born in northern Italy in 1943) and George Passmore (born in Devon, England, in 1942) met in art school in Swinging London in 1967. It was a wild time to be there. Mild-mannered male singing duos — Peter and Gordon, Chad and Jeremy — topped the charts while the Beatles dropped acid in India. Middle-class hippies and working-class kids faced off. Pop was already old; Conceptualism was starting.

Gilbert & George fed off all of this, but also backed away from it. Self-described country boys in the big city for the first time, and a committed couple, they stayed away from the art school set and instead moved to what was then a derelict East London, where they lived cheaply, saw almost no one and did their thing.

What was their thing? Some would call it performance art; Gilbert & George called it sculpture. An early piece, "Underneath the Arches," was a kind of tableau vivant. It entailed their posing together for long stretches — eight hours in some cases — and barely moving as they lip-synched the recorded music-hall song of the title, about the melancholy joys of the homeless life.

In London in 1970 they presented it free on the street for passers-by. In galleries, they performed it standing on tables, their skin covered with blotchy bronze makeup that made them look diseased. You can see a 1974 performance in a video in the show. Like much of their art, it is striking, then maddening, an endurance test for artists and viewers alike.

By then they had fixed on the odd-couple look they would keep: Gilbert, short, dark-haired, cute; George, taller, spectacled, blond-going-bald. With their blank faces and matching, slightly too-tight suits, they suggested overgrown schoolboys or modish clerks, part of the present but also part of some undefined past.

In the early 1970s they translated their live sculpture into more permanent mediums, first large drawings — a gallery in the show is devoted to these — and then into photographic ensembles. Initially the photographs were small, but of varied sizes and differently arranged from piece to piece. Then a set format developed: four or more same-size framed pictures — black and white, sometimes dyed red — grouped edge to edge as a rectilinear unit.

This simple solution allowed the work to expand in size incrementally, and it let the artists focus on what really interested them: content more than form. The images they used, shot in and around their East London home, were a provocative mix: rotting buildings and empty rooms; homeless men and jobless youths; racist graffiti and street garbage; gray skies, spring flowers, drunken nights, hidden sex.

The ensembles they made from these images perfectly caught the look of mid-'70s London, a bone-cold, bad-air town. It also caught the social heat of years when an African and South Asian immigrant population and a violent, white-nationalist reaction were growing apace. The artists' impassive recording of these tensions led them to be accused of racism and fascist sympathizing, although far from being politically prickly, their work comes across as elegiac, in a wry Philip Larkin-esque way: life is nuts; it has its beauties, but it's a losing game.

Then, in the 1980s, prosperity returned, and art reflected that. The pictures grew to mural size; black and white gave way to punchy Pop color; the cast of characters grew. Gilbert & George continued to appear, now joined by ethnically mixed crowds of attractive young men, some fresh-scrubbed, others with the slouch of street hustlers.

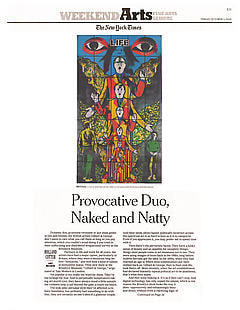

The four-part "Death Hope Life Fear" (1984), big as an altarpiece, bright as a stained-glass window, has an army of them, with Gilbert & George soaring upward on either side like exuberant guardian angels.

In the early 1990s, when the full impact of AIDS became clear, the work changed further. The young men in the pictures decreased in number. Images of giant flowers and fields of tombstones recurred, as did the figures of the artists, now naked and self-consciously hugging and vamping. Emphasis fell on bodily fluids, with microscopic close-ups of blood, spit, tears, sperm and urine used as a decoratively patterned backdrop for everything else. Disease isn't just inside us, the message seems to be; we are living inside it.

This perspective is fundamental to Gilbert & George's art: existence as a pathological condition; prognosis, terminal. Only an invented, illusory state called normality protects us from sinking under this knowledge. And maybe this idea of normality as a sort of false state of grace helps explain the George & Gilbert persona: the unchanging look; the well-practiced routines; the crisp, clean art that makes chaos graphically readable.

And maybe the chaos has been gaining the upper hand. The newest works in the show, from 2005 and 2006, are crazy, end-of-time stuff. Black, white and blood red are back. Terrorism and religious fundamentalism are the themes. Gilbert & George have always trafficked in religious imagery: crosses, churches, people praying, rosy Edens, martyrdoms and ascensions. More recently, much enhanced by digital manipulation, the supernatural has grown almost comically monstrous.

In "Fates" (2005), the artists are howling gods or demons communicating through coded Masonic and hip-hop gestures. In "Bomb" (2006), they stand, rigid and staring, framed by dozens of headlines: "London Terror Bomb Plot," "Bomb Victims' Funeral," "Bus Bomb: The Full Story." They wear the same tailored suits they wore as the vaudevillian performers of "Underneath the Arches" almost 40 years ago, but now they have moved their act to Club Armageddon.

It is difficult to make such historical connections in the exhibition itself, as the work is, unusually for a retrospective, not arranged by date. Instead the emphasis seems to be on compare-and-contrast symmetries, thematic correspondences and so on, which together create a total-immersion visual experience rather than a coherent career narrative. Over all the approach is effective, making the show a series of symphonic crescendos. Stand in any one gallery and you get a concentrated hit of the big career picture.

And one gallery might be enough. A little Gilbert & George goes a long way. In even moderate doses — and this show is immoderately large, spread over two floors — the work wears you down, the way the obsession-driven work of certain self-taught, or outsider, artists does: Henry Darger's convoluted erotic narratives; Madge Gill's through-the-looking-glass filigree epic; Howard Finster's symbolic sagas, at once ecstatic and accusatory, of salvation and perdition.

In the end Gilbert & George may be best understood within an outsider tradition. They are, of course, veteran and savvy insiders in the international art scene. They have been influenced by other contemporary artists, Joseph Beuys among them, and they have in turn had a significant effect on younger artists.

Yet at some level they have sustained the position of removal that they established in the 1960s as maverick artists, as a same-sex couple, as country boys. And this removal, this never-quite-fitting-in, is their strength.

It helps explain why they attract, in equal degree, admiration and hostility, and why the art world never really knows what to do with them. It may also explain how they have been able to keep their creative energy intact for so long, staying on track, but continually developing and enhancing the product. And it may explain the features — outlandish self-exposure, unmeasured moral outrage, and a belief in love, death and no heaven — that makes their art both all but unendurable and right for right now.

"Gilbert & George" runs from Friday through Jan. 11 at the Brooklyn Museum, 200 Eastern Parkway, at Prospect Park, (718) 638-5000, brooklynmuseum.org.