A few days after the closing of his exhibit Liberty and Orders at Lehmann Maupin Gallery (March 29 – April 21, 2012) artist Nari Ward paid a visit to the Rail’s headquarters to talk with Publisher Phong Bui about his life and work.

Phong Bui (Rail): Denise Markonish, the curator of your last show at Mass MoCA, Sub Mirage Lignum (April 2, 2011 – February 27, 2012), begins her essay for the show’s catalog with a definition of the word “gleaner,” which refers both to Jamaica Gleaner News Online and to the famous painting by Jean François Millet, “The Gleaners.” She goes on to explore the rapport between your memories of the past and your urgent need to situate them in your present life; she concludes from your work that you have a profound sense of labor. Because of her reference to Millet’s “Gleaners,” I can’t help but think of van Gogh’s admiration for and identification with Millet’s portrayal of peasants in their working environment. Van Gogh, in fact, began his vocation as a painter by copying Millet’s dignified, empathetic depictions of field laborers. I’ve always thought their physiognomies were portrayed as slightly misshapen, their bodies awkward yet robust, because life had made them so. That’s something I can certainly relate to in your work. Your forms are bold, monumental, and unwieldy. Where did your sense of labor come from?

Nari Ward: You know, I was just in a big group show in Beijing and participants were there at the gallery installing their work. While most of them would come in at 11:00 a.m., work for two hours then have a long lunch and quit at 6, 7 p.m., I would never fail to come in at 9 a.m. and work till one or two in the morning. I occasionally said to myself, my God, what am I doing? They’re all off to dinner, getting drinks, having a nice time, and I’m here working away. But I also realized that this is my entry into the work. For me personally, I need to get involved with the physical aspect of the work first before it can emerge as a catalyst for a kind of mental connection that needs to happen in terms of building the momentum and the rhythm. This only happens when I get the repetition of the labor established. My friend, the artist David Hammons, once said to me while we were sitting out in front of the Studio Museum in Harlem, “Nari, they love to see you sweat.” Of course, he meant that people value your sweat, not your thought, whereas he was interested in the latter. In my case, I have to say that I need both reciprocally, but it does get frustrating sometimes when your peers are in the nightclub and you’re sitting there trying to figure out what you’re going to do for your next move [laughs]. I also feel my sense of labor has deep roots in my working class upbringing. My mother worried about me being an artist and feared that I couldn’t make a living. I asked her to come and see my work at my M.F.A. thesis show at Brooklyn College, and I was very nervous and worried about how she was going to react to what she saw. I had all these black plantains hanging from the ceiling. It was a big installation; I really put a lot of work into it. She really looked at it carefully, then at some point I went over and said, “Mom, what did you think of the piece?” And she said with a positive affirmation, “Son, you did a lot of work.”

Rail: [Laughs.] I earned my mom’s affection with a similar work ethic.

Ward: Again, for me labor or work on that level translates to value and I don’t think it’s a class thing. It was how I was brought up: I really like sweating.

Rail: Unlike Duchamp, or any artist with a similar temperament, who wouldn’t like to sweat [laughs]. In any case, you and the sculptor Arthur Simms have similar backgrounds. You both grew up in St. Andrew, Jamaica, except that Arthur is two years older than you—he was born in ’61, you in ’63.

Ward: Right.

Rail: You also went to the same graduate program at Brooklyn College. For Arthur, who started as a painter, it was his experience at Skowhegan in 1985 that led to him discover that he was an object-maker, which connected him back to his early childhood when he used to make all sorts of found materials. For you, did sculpture come immediately as a natural calling or was it a sudden shift in medium?

Ward: My Skowhegan experience in the summer of 1991 was also a benchmark change for me as well. I remember clearly how Barbara Lapcek, who was the director at the time, said in her usual induction speech we all were la crème de la crème and if we were going to do the same work that we usually do, we’re basically wasting our time. She insisted that we should really try to explore and do something entirely different. I thought she was absolutely right. And since I had just been doing drawings throughout graduate school, mostly abstract and process-based drawings with all kinds of unconventional methods to make various marks on the paper, I thought of land art or earthworks, which I had never done. And that was what I did. I decided to experiment with the natural environment surrounding Skowhegan. And that experience really carried with me when I came back to finish off my last year of grad school. I was also living in Harlem, which at the time was a desolate and crime-ridden neighborhood. As a matter of fact, there was a lot of flight: people were leaving their apartments, buildings were being abandoned, there were empty lots so I was able to look at all these remnants that people left behind and they really inspired me to see the narrative in each of those found objects. I had an equally significant experience in a store with a fellow who tried to educate me about the difference between a fake African sculpture and a real one. He showed me some of the authentic pieces, which meant that they were used for various ceremonial purposes. And as for the fake ones, in order to make them look old they would bury them under the ground for a while.

Rail: In order to get a certain patina.

Ward: Exactly. To be quite honest, I didn’t really see much of a difference, which impressed me. I was interested in how that fiction could be created and so I thought I wanted to make series of fictions for these remembrances of marks. The drawings I made were more about the situation being the forefront of interest, rather than trying to frame them in a Western or non-Western visual language.

Rail: What did they look like?

Ward: Strangely enough, they were a lot like Clyfford Still. Although they were small in scale, the treatment of the image and the figure/ground relationship was pretty frontal and aggressive even though they were tonal and burnt, which created this element of light coming from behind. But it was definitely the process that I was intrigued with.

Rail: So the two experiences, Skowhegan/Harlem, converged, which shifted your work from drawing to installation work?

Ward: Yes. Recognizing the urban landscape as a site, and realizing the potential of making works out of found materials was a life-changing experience for me.

Rail: You must have seen the first show Dislocations that Robert Storr curated at MoMA in 1991 when you were at Brooklyn College. It was an important show for me because it was one of the first shows that not only linked the museum’s modernist commitment to post-modernism, or the lively scene of contemporary art, but also gave full presentation for installation art, showcasing seven installations by seven artists.

Ward: Chris Burden, Adrian Piper, Louise Bourgeois.

Rail: Sophie Calle, Bruce Nauman, Ilya Kabakov.

Ward: And David Hammons.

Rail: Yeah, and it was Hammons’s and Kabakov’s pieces that really blew me away—I mean, they really assaulted the “white cube” ideology and confines. I remember distinctly there was an image printed on the partition of a Native American walking with his hands holding the right leg of the white equestrian, Theodore Roosevelt.

Ward: Which is the sculpture that sits right in front of the Museum of Natural History.

Rail: Exactly! And Hammons showed both frontal and side views of it. Surrounding stacks of sandbags, police barricades——

Ward: And confetti.

Rail: Yeah, it was like a somber celebration of death. It was pretty in every way: politically, socially, and aesthetically.

Ward: I agree. I saw that show and it was certainly important for me, though it took me a while to realize that it has some relationship to my own Skowhegan/Harlem experience.

Rail: His alertness to random possibilities and his ability to accept the impermanent nature of reality are just a couple of Hammons’s many amazing attributes. When and how did you get to know him?

Ward: I met him on 125th Street while I was an artist-in-residence at the Studio Museum in Harlem in 1992. I would periodically see him up and down the street because at that time he lived very close by. So at some point I just struck up conversation with him and he was very friendly. I said to him, “Hey, I really admire your work.” He said, “Oh, so you had some young bloods checking me out.” “It’s exciting and I enjoyed your show, the PS1 show.” “Yeah, I’m the king of alternative spaces.” And I said, “Oh, really, I must say I don’t quite understand,” to which he said, “Yeah, but I don’t really want to do that shit any more, I don’t want to do anymore alternative spaces, I need to get into a good gallery.” It was a very strange conversation I didn’t expect to have with him. Nevertheless, it was interesting in that at that time the art world wasn’t as ready for him as it has been in recent years. Something similar is happening now: you’re seeing a lot of young artists, myself included, getting access to these galleries that were once off-limits in the past. I think the phenomenon of artists like that getting access to the so-called blue-chip realm is simply due to the changing consciousness of the collector. We’re in a very interesting time in that it’s the collectors who have the power and they set the agenda for the museums.

Rail: And the museums follow them.

Ward: Right. And that was basically the condition that I came into as a young artist. On the one hand, there were people like Hammons who struggled with breaking into the mainstream, and on the other there were instances like Kara Walker where she’s adulated as a very young artist. And for good reason. I’m able to see both of those things in a really interesting way.

I teach at Hunter College, and one of the great things about teaching is that it’s a give-and-take experience. I’m very excited to participate in discourse with young people who are really engaged and curious and question art and contemporary culture. For example, I have this student who was studying Nam June Paik’s work, and he spoke to me about Paik’s hope for television as a leveling technology. He thought television had the potential to create a globalized sphere where everyone is exposed to the same stew and we ultimately become homogenized beings. Well, with the diversity of new media and Internet technology, perhaps we’re getting closer to that paradigm. I think it is an opportunity to allow history to be built and written not just by the victors: now it can include other voices, which can interject necessary counterpoints.

Rail: I couldn’t agree more. Meanwhile, can you talk about how you relate to the materials that you choose on spot to work with?

Ward: I’m definitely led by the choices I make, whether with the subject or the materials, which can inform each other. I take real solace from the decisions I make in terms of materials: whether they be blankets or tarps, they will open up a new discourse for the next body of work.

Rail: Can we talk about your employment of repetition, or, let’s say, recurring motifs? For instance, I noticed that you’ve used baby strollers, shopping carts, and snowmen at various times and in different permutations.

Ward: Those are my safety net. They’re certain forms which I can rely on as my staple. They’re simply my sounding boards as well as my grounding elements. For example, when I started my residency at the Studio Museum, I decided to collect all the baby strollers that were abandoned, especially those that were used by so-called marginalized people to collect their bottles and cans and then were left in the lots. What got me doing that was, in walking around the neighborhood, I would see so, so many of them. All these objects were cast off once they weren’t functional any longer; someone might use the stroller to move bottles from point A to point B and then discard it once they collected their money from recycling. So I started thinking: these things have a story, they’ve been tracking through a landscape the whole history of information, whoever used them. That’s why “Amazing Grace” was the first piece that kind of brought me to start mapping the city in a different way for my own good.

Rail: I always like what Hammons said of his objects: “Each of them has a spirit already in it.” The process of redeploying them makes them come alive in different forms predicated on highly political and social issues, very different from their previous use.

Ward: Right. My strategy was not to collect just one or two beat-up strollers, but 365 of them, one for each day to make up a whole year.

Rail: So it would be fair to say, Nari, that to you it’s narrative-based more than just a formal use of repetition?

Ward: Yes. The formal aspect is incidental, secondary to this desire to charge them with energy and to give them a voice. As a smaller group, maybe the voice is muffled, but as a larger group it’s undeniable. Another important thing for me is that I always wanted the installation of those seemingly insignificant things to be directed so that they actually become elements for infiltrating the space and recreating the experience of the space for the viewer.

Rail: You’ve spoken in the past about your admiration of Robert Morris and other minimalist artists as well as conceptual ones like David Hammons. What about artists like Thornton Dial, Royal Robertson, Lonnie Holley, and Hawks Bolden, just to name a few, whose works are rooted in their community and who are committed to the cultural continuity of African-American traditions of the South? Genres and movements like blues, jazz, gospel, and soul, of course, came out of similar enduring commitments to heritage.

Ward: Well, I’ll tell you a really good story. I had my first museum show in the project space at the New Museum, and I did a piece called “Carpet Angel” and the curator Frances Morin, who’s a friend of mine, said, “Nari, the next show was going to be a retrospective of Thornton Dial. Would you like to meet him?” And I said, without knowing who Dial was at the time, sure. Soon enough, she took me down to Bessemer, Alabama to meet Dial and it was there that we also met William (Bill) Arnett.

Rail: Who along with his brother, Paul, and son, Matthew, have been tireless advocates and champions of African-American vernacular artists since the ’80s.

Ward: Exactly. And then Bill took us to meet Lonnie Holley on the same trip, and I was blown away by both of Dial’s and Holley’s works. Oh, man, the energy generated by their works was titanic, just fantastic. That experience has, in fact, reinforced my skepticism about these idiotic labels that are thrown onto their works, like “outsider art.”

Rail: I couldn’t agree with you more. Do you think, in addition to your natural rapport with found materials, you have disdain for the overt wastefulness in capitalist consumer culture where everything is thrown away after having been used once? I’m, of course, thinking of how you recycled materials left over from three previous installations at Mass MoCA: Tobias Putrih’s Re-projection, Hoosac (2010); Anselm Kiefer’s Sculpture and Paintings (2007-10), and Iñigo Manglano-Ovalle’s Gravity is a Force to be Reckoned With (2009).

Ward: Definitely. This is a question I ask myself constantly: What is it that draws me to these discards, which people don’t seem to value anymore? And why am I trying to put value into them? How did I get so sensitized to those things? Those are tough questions, and I have never been able to find the right answer for them. But I always feel an element of faith and have a visceral connection to things that have been used. I’m attracted to their energies. For example, if I’m standing in front of a pile of wood that someone has thrown out, I immediately feel that I have to figure a way to work with it, to make it come alive in another form. To me it’s collaboration between the material, whatever it may be, and me. It’s a dialogue that needs to be cultivated, and that process is always about transformation, taking one thing from one state and applying energy to create another kind of situation. “Nu Colossus,” for example, is about a re-creation of my memory of Star Trek; one of three programs that were available on television when I was a kid in Jamaica—the others being the news and Bonanza. Those images combined were etched into my unconscious. In fact, when I look into “Nu Colossus,” which was improvised on the spot, I say to myself, “This is the Enterprise going into Warp Drive.” It’s about movement into another kind of space. I really wanted this dormant state of the material to fly through the air with the viewer. But again, in the beginning stage, I was more concerned with how to make it work structurally so the overall image wasn’t as clear as it was later when all the labor was done [laughs].

Rail: “Nu Colossus” actually reminds me, in terms of form and scale, of the monumental piece that you had with the Chinese artist Chen Zhen (from Archipelago: Crash Between Islands to In(ter)fection, 1998,) the difference being the latter was hung from the ceiling, and the former was partly propped up by the floor, which has a different connotation altogether.

Ward: That’s true. In fact, when Jérôme Sans, the curator for that show, put Chen and I together, it happened to be a maritime museum, so from the very start we felt that, in reference to boat, the floating form was a good starting point. Then as we began our dialogue we both realized that one form entering the other was very sexual [laughs], but we all thought it was an interesting metaphor for a kind of cultural conversation. It was a magical experience.

Rail: If you can allow such collaboration in the visual arts as tools for cultural diplomacy, like the way celebrities like Angelina Jolie are being asked to be Goodwill Ambassadors.

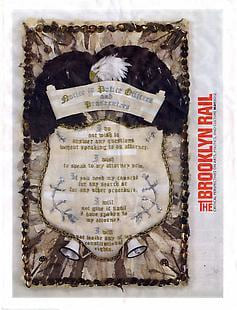

Ward: Good point. I’ll tell you about one strange incident: I got a call from the N.Y.C.L.U. to talk about my show, Liberty and Orders, and the issues that it raises with things like policing. Since I’m not an activist the whole conversation was about me trying to be a cultural diplomat. I tried to talk about how my personal interactions with situations in my neighborhood became a catalyst for thinking and looking at bigger possibilities or bigger questions. So it went from the factual world, which lawyers are involved in, to the fictional, a world that I am trying to create. In some ways law is about trying to contain, label, and define information, and as an artist, we’re all about obscuring, layering, or creating other possibilities. They’re almost antithetical, one to the other, so the idea of putting them together in one conversation is tension-driven, but it’s also hopeful that these two realities could exist in the same form.

Rail: I notice that many of the titles of the pieces use legal vocabularies.

Ward: Exactly. But the idea of being diplomatic with great passion really interests me. It’s not just a simple gesture, the real labor has to be behind it.

Rail: Yet, in spite of the seriousness of the subject matter and the large scale of some of the work there is, I feel, a definite ephemeral presence in all of them, whether it manifests in the use of the materials, for instance, “We the People” and “Scope,” which are made with shoelaces, or the instability of the structure in “T.P. Reign Bow.” Is that your intention?

Ward: Well, for one thing: I didn’t want it be too literal in its translation, although it was generated from my joy and anxiety at having gone through the process of naturalization. I wanted it to be an image of authority and I didn’t want it to look shanty-like either, but at the same time I wanted to convey a sense of balance between control and freedom. There is also a mascot in the work; a red fox with an afro tail that I call Cornel after Cornel West. Cornel is staring at a rope of pants zippers with human hair stuck in their teeth. The rope of zippers hangs from the window of the police platform like Rapunzel’s hair; this introduces an element of vulnerability and potential escape.

Rail: I want to ask you about your short text (“A Simple Twist of Fate: Tour Guide”) published in the catalog for the show at the Palazzo delle Papesse in Siena, which was written like a prose poem. I thought it was pretty intense. In it, you talk about a waitress in Siena asking you for payment before the meal. Did this really happen?

Ward: Yes, but I wasn’t angry with her. The thing is people are often the product of where they come from and how they relate themselves to their environment. I’m sure she hadn’t traveled the world that much, and there was no reason for her to think beyond what she was exposed to.

Rail: She was a product of her perpetual provincialism.

Ward: For sure. One of the things I wish that I could do one day is create a program for inner city kids in which they can travel the world, experience the complexities and greatness of different cultures so that when they return they will be changed.

Rail: Last question: How was your graduate school experience at Brooklyn College?

Ward: It was great. I was lucky because everyone was there at the same time: Philip Pearlstein, and Lee Bontecou especially, who was exceptional because she was very thoughtful, even when she was critical. She could always sum a critique up with something supportive. A lot of humility and intellect is what I’d say about her.

Rail: And William T. Williams?

Ward: William T. was great, equally supportive. He never imposed his ideas of art on any of his students. What happened was I knew Al Loving, and Al was so generous. When I told him I was looking into grad schools he said, “Man, you should go and see William T.” I was thinking of applying to Yale, and thought maybe if I was good enough I could get a scholarship because I didn’t have any money, and he said, “Oh, go see William T., he’s a Yale grad, he’ll hook you up.” So he called William T. and asked him, “Can I send this guy over?” And William T. said yeah. So I went, I brought my little portfolio, my drawings, over to William T. with the intention of asking him to write me a letter of recommendation for Yale. He looked at the work and said, “Yeah these are good, what about going to Brooklyn College? Yale is fall admission, why don’t you think about this?” And I was just trying to appease him, like, “Right, maybe I should try and think about this place,” and he said, “Alright come on,” and I said, “What?” He walked me into the admissions office and said, “I want this guy enrolled.” That really blew me away, and I knew right away that I wanted to be under his tutelage. And he really stuck by. Every time I asked him to take a look at my work he’d come through. Allan D’Arcangelo was another big support system. This all happened just before the administrator offered early retirement so they all left at the same time, maybe a year after I graduated.

Rail: What was your relationship with the painter Emily Mason?

Ward: I was working night shift at Barney’s as a security guard from 9 p.m. to 9 a.m., and since I lived all the way uptown it didn’t make sense to go home for an hour—Emily’s class was at 11 a.m. So I would sleep in the library, and a few times I overslept or I would go to her class with my eyes all red, looking like a drug addict. And she said, “Nari, what’s going on?” I told her the story, and from then on, on her way to the class she always stopped by the library to wake me up to make sure I didn’t oversleep. She also did something that I think changed my entire notion of the possibility of being an artist: she gave me one of these Angel grants to go to the Vermont Studio Center. Before that I didn’t know artists, I didn’t know the lifestyle of being an artist. I didn’t have any role models back then. At the Center, I saw fine artists who were doing their work, and they actually weren’t crazy, weren’t biting their ears off. That’s when I said to myself, “I can do this, I can do this.” I’m going to go for it, and became an artist. Without that experience I’m not sure my life would have turned out the way it did.

Rail: Well, everybody needs a little push. I love what Jonas Mekas said: “What we all need is a little push. Like an infant being born all he or she needs is a little push by the midwife.”

Ward: That’s true, and that can change everything. Otherwise, there are some people who never got the push and they’re stuck forever.