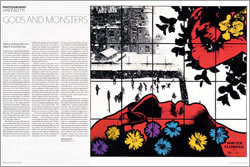

GODS AND MONSTERS

Taking photographs the Gilbert & George way

In the lead-up to their "Major Exhibition" at Tate Modern, Gilbert & George talked to a number of journalists. Perhaps because their art has always involved performance, they tend to treat interviews, no matter how sketchy and superficial, as an extension of their work. The promotion of their first and most extensive British retrospective in 25 years provided the perfect opportunity to issue pithy manifestos and trot out their famously conjoined personality, a volatile mix of awkward formality, lacerating frankness, unsettling coziness, and brittle wit. Though not as aphoristic or blase as Warhol, who set the standard in this field, G&G can entertain when they choose to, and they apparently warmed up to writer-presenter Janet Street-Porter, who interviewed the pair for British Harper's Bazaar. She gets them chatting about their newly fashionahle neighborhood, their eating habits, the television programs they watch, and why they never go to see other artists' shows ("We have our own vision of the world and don't want to be'contaminated," Gilbert says), When she comments that they'd seemed "unbelievably polite" whenever she'd seen them at the Venice Biennale, Gilbert (the Shit) says, "We aren't rude and we don't swear." George (the Cunt) adds, "That is why we can get away with so much in our art." Well, that explains it.

All of G&G's exchanges with the press veer unpredictably between primness and provocation, and this one ends with a cheeky nod to their reputation for outrage. Because the newest pieces at the Tate incorporate handwritten headlines from placards used to hawk the Evening Standard, London's most widely read

tabloid, following the 2005 transit bombings, Street-Porter asks the artists to imagine the headline that would greet their show. George doesn't hesitate: PERVERT DUO DESECRATE TATE MODERN. (By the time the exhibition had opened, a framed, limited-edition print of that imaginary placard, with the Evening Standard logo at the bottom, was available from White Cube.)

They've certainly kept their word: G&G's desecration of the Tate is spectacular and relentless. With more than 200 pieces, from vitrines of early "Postal Sculptures" (1969-75) to the multipart, mural-size images that define their mature work, the exhibition fills every nook and cranny of the museum's fourth floor, including the espresso bar and the open concourse. No matter how (over)stimulating, this is more than most viewers will have the stamina for; even worshippers at the shrine of "The Singing Sculpture" are likely to flag before the final stretch of rooms. But how could it be otherwise? For all their formal sophistication and restraint, G&G are about excess, sensation, and information overload, They have no interest in soothing or pleasing the viewer. George (in a 1982 conversation): "If a picture doesn't say 'fuck you,' it's no good anyway. It has to defy the viewer first of all, then it can go on to say other things. ... [Viewers] must not feel as though they know something-then it's all wrecked .... You want them to stand in front of a picture and say, 'What the shitting hell does this mean to me?'" If their retrospective were anything less than ovenwhelming and aggravating, it would have failed, (For the ultimate OD, see Gilbert & George: The Complete Pictures, Aperture's new, massive, and shockingly affordable two-volume catalogue of work made between 1971 and 2005.)

For anyone interested in the contemporary confluence of art and photography, G&G are crucial, pioneering figures, along with the equally maverick Lucas Samaras, John Baldessari, and Ed Ruscha. Although G&G's earliest pieces were mostly conceptual and "sculptural," following a series or large-scale charcoal drawings in the early 1970s (also referred to as "sculpture"), their work has been entireIy photographic. What it has never been is conventional. Even when they were showing small black-and-white photos of foliage, urban facades, woozy interiors, and their own identically suited selves, they hung them in meandering clusters and eccentric installations. When in 1976 these arrangements coalesced into grids, each element of which was framed in a thin black band, they found the format that has identified their work ever since. No image stood alone, but any suggestion of narrative was fragmentary and elusive. They weren't telling a story; they were building a myth-a crazy, fuck-you universe-bit by bit,

From the beginning, their world was self-centered and homoerotic. It included their house, their street, their immediate neighborhood-London's tough, derelict East End-and their (male) neighbors, but it revolved around their own bodies, faces, desires, anxieties, and aggressions. G&G's bland anonymity and office-drone attire briefly allowed them to play Everyman as outsider and sexual outlaw. But they were also gods and monsters: observers, manipulators, worshippers, followers, and leaders of an increasingly large and pointedly multicultural cast of handsome boys and young men who occupied their photographs like proud proletarian heroes out of socialist-realist paintings. Women don't exist in this world, even implicitly. The gaze and the objects of the gaze-some of G&G's most emblematic pictures consist of nothing else-are exclusively male, The artists imagine a place where underpants fall from the sky, crosses contain crotches, piss turns into a golden river, and beautiful boys join them in a kind of ecstatic comradeship. In the monumental sequence "Death Hope Life Fear" (1984), whose flat poster-paint colors suggest Indian carnivals, G&G are both awed, tiny figures among teenage giants and many-headed totemic icons offering warnings and blessings to their flock.

But if these are glimpses of a queer Eden, complete with neon-bright flowers, they're poignant and fleeting. G&G's army oflovers began to scatter at the end of the '80S, when AIDS had its most devastating impact. In a 1996 series called "Fundamental Pictures" and 1997's "New Testamental Pictures," the artists, who had already been dwarfed by giant turds, further mortified themselves by appearing alone and naked against the blasted landscape of their own piss, sperm, tears, and blood, all hugely enlarged from microscopic slides. They've talked about the importance of making themselves vulnerable to the viewer, but in a 1999 conversation with Wolf Jahn, George said that "there is a price to pay. You fuck yourself up in some way by doing pictures such as "Shitty Naked Human World." We become a little bit damaged, sexually or psychologically or emotionally ... it's quite dangerous."

Just how dangerous is apparent from the work that followed. The enormous, chartlike photocollages G&G began making at end ofthe '90S found them back in their neighborhood, recording the sort of graffiti, handwritten notes, political posters, and signs of neglect that filled their early world, now vignetted against a background of street maps or brick walls. Other people appear as fragmentary symbols (a row of staring eyes) or empty temptations (a solid wall of rent-boy ads), but even G&G look dehumanized. Their most recent pictures use digital programming to double and distort figures, objects, texts, and especially themselves until they all mutate freakishly, resolving into a series of kaleidoscopic Rorschach tests. Though the work is not without black humor, it feels angry, aggressive, and hopeless. Even if we could lind our way back to the garden, the flowers are bound to have withered and the boys are surely long gone,

Also nearly gone in the recent computer-derived images is asense of G&G's roots in photography. "We think of our art as just pictures, not as photographs," they announced in 1986. "We're using photography, not being photographers." This is a strategic but not particularly useful distinction. G&G's pictures may not be window-on-the-world photographs in the tradition that stretches from Fox Talbot to Thomas Struth the tradition they draw on includes the photocollages and photomontages of John Heartfield, Moholy-Nagy, and Hannah Hoch, but at a scale unimaginable to these predecessors. They're constructing, not simply documenting, a world. But their constructions are pieced together from many individual photo documents that the artists themselves have taken, and, no matter how fantastic, the work's impact is essentially photographic-its vocabulary is derived from the still camera (there's nothing cinematic about it). Without straying very far from self portraiture, G&G have turned a detailed record of the London they love and loathe into visions both heavenly and hellish all the more persuasive for being grounded in the photographic document: real trash, real boys, real shit, real flowers, real artists, "We don't want realism," they say, wTbe streets are always miserable." Their feat is to use realism to build a personal, compelling mythology that consumes not just their world but ours.

Gilbert & George: The Complete Pictures, is copublished by Aperture and Tate Publishing, "Gilbert & George: Major Exhibition" is on view until May 7 at Tate Modem, London.

PHOTOGRAPHY VINCEALETTI