Inside

2008

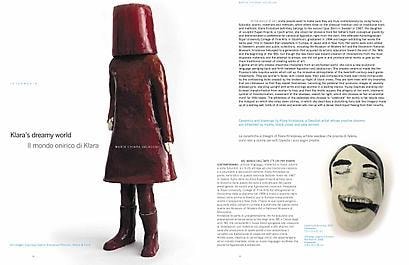

Klara's dreamy world

By Maria Chiara Valacchi

IN THE WORLD OF ART, some people want to make sure they are truly contemporary by using today's futuristic idioms, materials and methods, while others draw on the classical tradition and on traditional tools and methods. Klara Kristalova definitely belongs to the second type. Born in Sweden in 1967, the daughter of sculptor Eugen Krajcik, a Czech artist, she stood her distance from her father's hard conceptual plasticity and demonstrated a preference for canonical figuration right from the start. She attended Konsthogskolan Royal University College of Fine Arts in Stockholm, graduated in 1994 and began exhibiting her works the same year, first in Sweden then elsewhere in Europe, in Japan and in New York. Her works were soon added to Sweden's private and public collections, including the Museum of Modern Art and the Stockholm National Museum. Kristalova belonged to a generation that acquired its artistic education toward the end of the '80s and the beginning of the '90s, but though the new trend was toward creation of installations from the most disparate materials and the attempt to amaze, she did not give in and produce serial works or give up her more traditional concept of creating works of art.

A gentle artist who creates dreamlike characters from an enchanted world, she coins a new sculptural language swinging back and forth between figuration and abstraction. She creates ceramics made like the Picasso's late majolica works which call up the innovative atmospheres of the twentieth-century avant-garde movements. They are women's faces, with closed eyes, their pale complexions made even more immaculate by the contrasting locks created by the broken-up flight of black crows. They are dark trees with dry branches that are interwoven so that they repeat themselves, becoming the pedestal that produces images of severely dressed girls, standing upright with arms and legs akimbo in a waiting stance. Young Daphnes standing still to await transformation from woman to tree; and then the moths appear, the allegory of her work, shamanic symbol of transformation, movement of the shadows, search for light, which she chooses as her ornamental motif for little boxes. The whiteness of the pedestals she chooses to "celebrate" her works is her tabula rasa, the notepad on which she notes down stories, in which she describes a disturbing fairytale like imagery made up of a wishing well, birds of ill omen and women who rise up with a dense, black liquid flowing from their mouths.

Her watercolours and pencil draw the transfigurations of her own sculptures on sheets of paper, framed in light wood. They are light, spontaneous drawings that seem to be created by an uninhibited mind or by the unselfconscious hands of children; they recall the creations of outsiders to society, of the mentally ill, like Dubuffet's art brut, an art that does not seek to be aesthetically pleasant but expresses primary emotional drives, simultaneously describing our deepest impressions.

Klara Kristalova does not seek stylistic perfection in her paintings or sculptures; the forms she models are merely hinted at, the colours applied without precision, intentionally blurred, following the natural flow of the colourful liquid and blending to create unusual hues. Her primary interest lies in the message, the description of a story, the origin of an object that can bring to mind memories of childhood. The same intentional innocence characterises her themes, as in one of her works in which a two-toned bronze circle supported by a hand runs in perfect balance along a wall like Humpty Dumpty, the bizarre character in Alice in wonderland, the anthropomorphic egg, round and clumsy, walking along a wall and being careful not to fall off; or the famous mermaid, symbol of Copenhagen, which Kristalova reproduces in glossy majolica ceramics, with full, round breasts, a bright green fish tail and her face turned slightly toward her shoulder, resting on the smooth pebbles of a pond. These are the ex-votos, the votive statuettes of a religion that does not exist, which worships bold nymphs, female monsters representing women's pain. These little icons are sacred yet blasphemous compositions, divinities to be invoked with caution, which Kristalova chooses to exhibit on a long white table similar in shape and size to the one Leonardo da Vinci depicts in the Last Supper. In a mystical atmosphere, stories follow one upon the other, starting and ending within the very presence of the works. Blindfolded women who conceal the flow of blue tears, liquefied faces, features hidden by an unnatural growth of flowers or by moths hovering happily in search of light. It is a circus of emotions, of monsters, of contemporary nightmares. Her feminine softness exposes today's dreams and oppressions, the anxieties of the subconscious, dragging them out and transforming them into visual metaphors. Woman becomes the absolute witness of anguish, which Klara Kristalova describes with drowning in dark viscous liquids, with teardrops out of which formless bushes grow, or with genteel cut-off heads, like rocks, stacked in a wooden crate full of stones. She uses the power of the classical vocabulary to bring together characters and places out of her imagination, and with the ritual addition of material in her sunny studio in Norrtalje, Sweden, she makes little forests of brown mushrooms, circus tents, lost boxes and rivulets of water. She daintily sips material, choosing the best finish to represent the evocations of her subjects. Her preference is for a shiny, bold lacquered red for a girl standing up, with a bucket on her head, unconcerned about seeing what is around her, about entering into visual contact with the onlooker; or else she chooses dark opaque clay for an African mask, with white eyes and a mouth created by a grid of squares. Her nice, light little worlds fall into an entirely feminine hemisphere. It is obvious that her works were created by a woman. With no need for facile sexual references, or for attempts to oppose the masculine in overly explicit language, she extols the male world by putting a pair of black trousers on a wooden base, hovering in the air supported only by the light flapping of the wings of two butterflies.