Gilbert & George’s Sculptural Life on Film

by Claire Voon

“Art for All” is at the core of artist duo Gilbert & George’s work, a slogan they champion in aiming to break from the trappings of an art scene they find elitist. Shedding their last names from their attributions, they identify as what they call “Living Sculpture,” embodying art by molding their own routines and actions into an artistic practice. Rather than more formal material, the self, and accordingly, personal experience, becomes their prime subject.

The pair recorded their early videos on the then-new technology of videotapes, four of which are on view at Lehmann Maupin Gallery’s current exhibition Films and Sculptures, 1972-1981. Each centers on the artists, who set themselves in everyday scenes such as eating or walking to narrow the distance between art, artist, and viewer. Gilbert & George’s use of film gives life to the seemingly banal, attempting to create meaningful experiences accessible to all through the common language of the human condition.

The idea of simply being, for example, takes center stage in “A Portrait of the Artists as Young Men” (1972), a video of the duo gazing impassively into an off-screen, seemingly far-off space. For the entirety of the piece, they make only slight movements with deliberate slowness, drawing out each blink or each turn of the head. Gone are the outstanding features of a classical portrait that leave an impression of its subject; we’re left with more of an anonymous depiction, which makes the act of existing into a statement but leaves little impression of its subjects and has one feeling distanced from the stiff men with their well-coiffed hair and matching signature suits.

Similarly, roaming a garden turns into a 16-minute-long, visual meditation with “In the Bush” (1972), in which the pair appears as barely discernible, phantom-like figures, their intentions unclear. There’s something about watching it alone on a small monitor that makes the scene compelling — albeit slightly frustrating — as if we’re viewing a program in quiet anticipation of some climactic moment that never arrives.

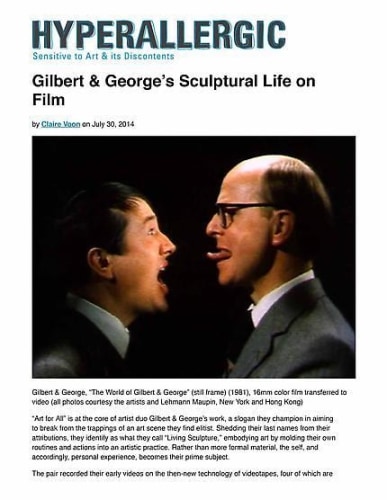

It’s fitting, therefore, that Gilbert & George’s feature-length film, the only one shot in color and projected on a wall in the gallery’s back room, is titled “The World of Gilbert & George” (1981). Composed of vignettes written and directed by the pair as a culmination of their imagery, it reminds us that the scenes on the screens are still products of the pair’s world rather than belonging to some universal vocabulary. Slow-panning surveys of the furniture and floorboards of the artists’ East End home are shown beside that of the London skyline; while these silent subjects reveal the living conditions of urban life from the privacy of a house to the public space of towers, factories, and churches, I’d imagine they would still speak most strongly to a Londoner. It’s also notable that while men of all ages appear in the film, no woman or girl receives any screen time — making the case for “Art for All” a little unconvincing.

One of the exhibition’s stronger pieces is the amusing “Gordon’s Makes Us Drunk,” (1972) in which the men — although still in their stiff suits — sit in armchairs and continuously down glasses of Gordon’s gin as a monotonous voice repeats, “Gordon’s makes us drunk” (this eventually becomes “very drunk” and “very, very drunk”). The act of drinking takes on an air of performance, accompanied by full orchestral renderings of Edward Elgar’s “Pomp and Circumstance” and Edvard Grieg’s idyllic “Morning,” and the somber scene becomes an endearing comedy. The highly stylized setup of Gilbert & George’s other films is most successful here, as it highlights the absurdities of society. This is emphasized in a contrasting scene in “The World of Gilbert & George” (1981), in which the artists sit perfectly upright at a breakfast table, extending niceties so robotic they become equally ridiculous. Here, humor reigns — and it is more through such subtle quirks than through certain objects or environments that Gilbert & George most adeptly turn projections of their own experiences into something more universally digestible.