In Hernan Bas’s exhibition at Lehmann Maupin, the artist punctured the notion that any given situation has a single truth or reality by highlighting the combination of fact and fiction that contributes to our perception of historical record, politics, news, or cultural rites. With the exception of the show’s single freestanding screen, each of the seven large-scale acrylic-on-linen paintings featured a young man, or groups of men, as the locus of a formally elaborate tableau which together took on a panoply of topics—the supernatural, homosexuality, mass media, fantasy, alienation, memory, and even the vast sublimity of the universe itself—rendered in an unabashedly fey manner that tweaks the machismo of history painting with sumptuous style

In The Occult Enthusiast (all works 2019), the protagonist is slumped at a table in his study, surrounded by a hoard of material on the paranormal. He leans on a stack of cryptozoology publications referencing the Loch Ness Monster, Atlantis, and the Necronomicon, H. P. Lovecraft’s fanciful grimoire. Before him are a Ouija board, a clump of burning sage, and an Independent Order of Odd Fellows apron, while the walls and shelves are glutted with taxidermied animals, skulls, masks, and ghoulish busts. Volumes from Time-Life Books’ Mysteries of the Unknown are prominently displayed. (The show’s title, “TIME LIFE,” was an homage to this series’ publisher.) In the foreground, a panel is filled with newspaper articles about the sale of the “Amityville Horror house,” UFOs, bigfoot, and other such subjects, all of which are connected by a matrix of red thread, the totality evoking a police evidence board. This device was expanded upon in Conspiracy Screen, a six-panel partition painted on one side with outlandish headlines screaming about run-ins with flying saucers and alien abductees.

We were thrust into a different kind of thematic terrain—temporally, psychically—with A Moment Eclipsed #1 and #2. In each painting, a boy stands, holding his catch—a hammerhead shark and a kingfish, respectively—in the clichéd pose of the triumphant angler. But the youths are not celebrating. Their faces register confusion or acquiescence. In #1, the lad holds the huge, phallic creature between his legs. However, his unsmiling demeanor suggests discomfort with the expectations of masculinity being placed upon him by his performance in this charade of victory. Standing on docks, the reluctant trawlers are figures who belong to neither land nor sea. They also appear indifferent to the dramatic cosmic events unfolding around them: a solar eclipse in the latter work, and a lunar eclipse with a bloodied moon in the former. The pictures seem to be allegories of adolescence: a time of betweenness, promise, and terror.

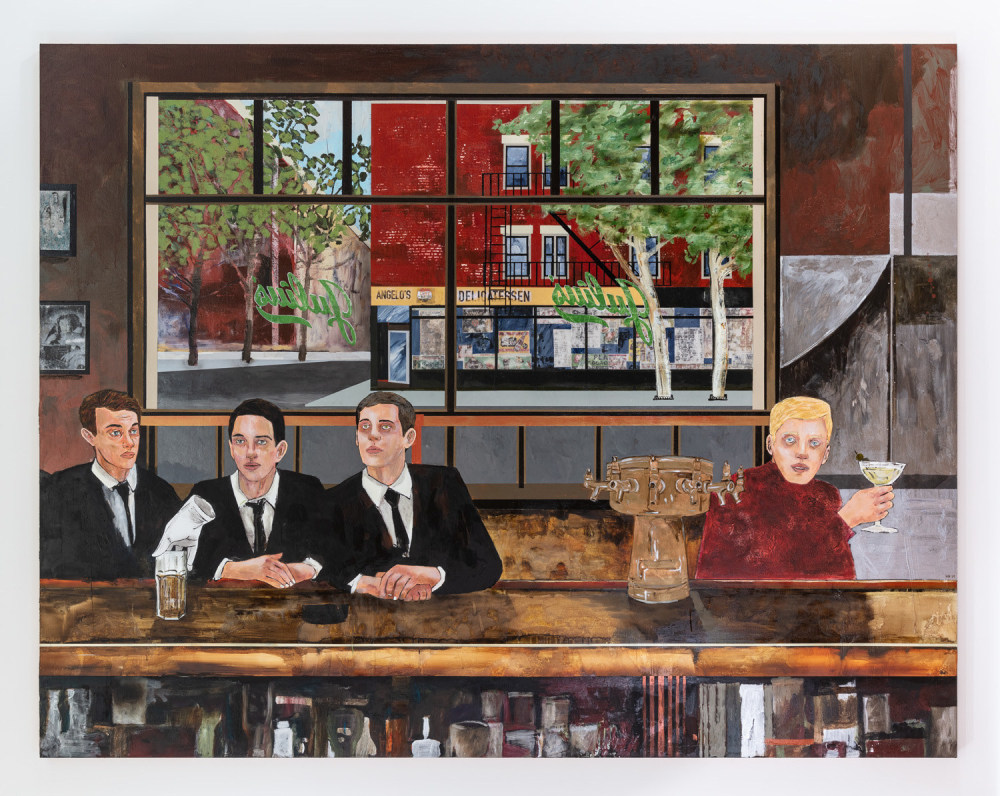

In the gallery’s front room was The Sip In, a work based on a 1966 press photograph of men from the Mattachine Society (an early “homophile” organization) sitting at the counter at Julius’ (one of the city’s oldest gay bars) in Manhattan’s Greenwich Village, protesting New York’s anti-gay liquor laws. The original image shows a bartender refusing service by placing his hand over an activist’s glass. Bas refashioned that moment by removing the offending barkeep from the painting, leaving only a white-gloved hand as a ghostly remnant of his rebuff, in a sly and refreshing bit of historical revisionism.

Typically, Bas’s compositions depict ephebes in reverie among (or dwarfed by) riotous swaths of natural abundance—gorgeous woodland, bountiful gardens, mystical swamps—or reposed in gracious rooms from bygone ages. They function as metaphysical set pieces, chock-full of references and suffused by a kind of magical queerness. Yet here, the artist focused each painting on a single interest. Bas managed to delve deeper into his obsessions and bolster his vision, which in turn heightened the mesmeric allure his images exert upon us.

Image: Hernan Bas, The Sip In, 2019. Acrylic on linen, 84 x 108 inches (213.4 x 274.3 cm)