Detroit-based painter Hernan Bas's works draw on Decadent literary precursors such as Huysmans and Wilde. Here, he discusses the unsettling atmospheres that he develops in his artworks, as well as those that he returns to in his memories. In a series of back-and-forth emails, the artist talks about the importance of unfinished stories, and the conversations that he would rather stop having in interviews.

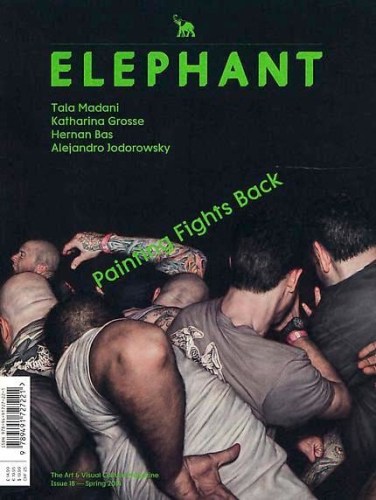

In marshland, any other kind of life feels removed, and the isolation of this particular one feels infinite. Stuck in those swamps are the darkness, mystery, fear and thrill of violent fairy tale and mystic folklore. To these landscapes - and other open, overgrown and abstract grounds - Hernan Bas adds the moving bodies of opaquely modern characters. Often, they're adolescent boys absorbed in thought and comfortable silence, or comfortable boredom, and the kind of unhurriedness brought upon by a heavy air and no place to be. These characters' insecure displays of confidence are evident in both the postures Bas attributes to them and the titles: The Prude Listening To Love Songs, The Big Winner. Bas mounts mundane existence, restlessness and slumped shoulders onto remote, dreamlike backdrops.

- Did you grow up around art?

I didn't really grow up around visual art, but my father was a well-known musician and singer [German Bas, who worked with the group Los Jovenes Del Hierro] in the years before I came into the picture. I'm one of six kids, so the idea of one of us being interested in the arts in any form was not particularly frowned upon. My father has recordings of me as a three- or four-year-old child expounding on how much I want to be an artist. It's a little spooky to hear now. I'm not a full-hearted

believer in past-life phenomena, but the vigour with which I described my future career as a kid makes me question it.

- Does the idea of an artist that you had back then seem accurate to you now?

I never had a romantic idea of being an artist. It sounds hard to believe, but I just grew up wanting badly to make images. My first works on canvas consisted of a tiger deep in the jungle and a polar bear nudging its baby into the water off of an iceberg. These were made on the occasion of my eleventh or twelfth birthday, and I was given enough money - about $40! -to buy a collapsible standing easel, three canvas boards, a set of acrylic paints and the least expensive wooden pallet I could afford. I guess that was my earliest conception of what it meant to be an artist: a wooden pallet to hold in your hand as you paint. Blame Bob Ross [host of the TV programme The Joy of Painting].

As a child, I thought that being an artist was about the excitement and desire to make an image, and that part is still there for me. The difference is that, as a kid, you don't have any comprehension of the amount of emails- yes, I'm old enough that emails would not have been in my mindset - and correspondence and office work that are required of you to run a functioning studio, especially one without any assistants. That said, I never had expectations, other than to be in a situation that required no 'other' job than being an artist. As long as that continues to be the case, I will always tell myself I am what I thought 'an Artist' could be.

- Did you move to Detroit for artistic or personal reasons ten years ago?

I'm not committed to year-round residence in Detroit anymore, but I still love it for the main reasons I came there: lots of inexpensive space and privacy. There's definitely a burgeoning scene in Detroit: between the DIA and MaCAO, there is a lot to look to, and they are being supported and run by really talented individuals. I honestly stay a bit out of the picture. I think it's my own backlash of not wanting to be called a 'Detroit artist'. There are a lot of people who have been there a great deal longer than I have, and I don't want any attention on me to steal a minute away from them. This might be the last time I answer a question about Detroit for an interview! It comes up a great deal, so from now on I'm going to start telling people to just go see for themselves.

- Then I'll bring up the other geography question you're always asked about in interviews: you grew up in Florida - does that landscape play a part in the environments to which you're visually attracted?

I was born in Miami, but my parents made the abrupt move to northern Florida shortly after my birth. My earliest memories are of the Ocala, Florida 'farm' my father moved the family to. It was isolated, or at least it felt that way. The roads at the time were still muddy clay, not asphalt, and we had what felt like miles of forest between us and anyone else.

I think that overwhelming fear and fascination with the unknown, with what the forests 'held', is imbedded in a lot of my work. So it isn't the landscape of tropical Miami so much as the southern gothic mood of northern Florida that I'm typically drawn to. It's hard to describe, but things grow differently up there. After moving back to Miami at age five, I have no memories of the bathtub water ever freezing over just from the outside temperature.

- The words 'dandy' and 'dandyism' come up often in descriptions and reviews of your work. Is this because you floated the word out there and it stuck, or because of some inherent quality belonging to your images?

One of my first shows in New York was titled Dandies, Pansies & Prudes, so I have made direct reference to the figure of the dandy in the past. But, since then, I have come to see my use of the dandy differently. Lately, I've been thinking of dandies as creatures, to some extent, like exotic birds. I've been looking a lot at nineteenth-century caricatures, in which dandies are often depicted as 'fops' - these lanky 'insects', as the famous caricaturist George Cruikshank described them, as opposed to the more refined, proper dandies, who came about as a rejection of ornate frocks and powdered wigs. Still, that image persists when we talk about dandies in culture, but it was a much more subtle and sophisticated character than we think of now. I suppose when I paint a dandy these days, it's something that isn't illustrated, I just see it personally in the characters and their actions, and the costume isn't even necessary.

- Your work seems to elicit some of the escapist thrills of a good work of fiction. Do you consciously draw from any techniques of literature or narrative in your art? Do you think of your work more as escapism or confrontation?

I loved Choose Your Own Adventure books as a child, which followed a format that jumped you across the book. Say the chapter ends, and you 're given three choices as to what page to turn to next: 'Does Johnny a) go into the scary cave, b) call up his chums for help, and so on. I like to think of painting in those same terms. Let the viewer finish the story: are they a couple? Is he going to make it across that stream? I like to make images that describe the middle of the story, maybe the intermission, but never the end.

- Even if the characters seem modern, your images suggest something from an earlier time or memory. Are there different tenses involved in your work - past versus present - and do you see their relationship as seamless or more of a struggle?

Unless I'm describing an actual character from history, fictional or not, I try not to date them, if at all possible. In the styling of characters, it's a lot of simple attire: T-shirt and jeans, maybe a recognizable Converse sneaker, though even those could be from 50 years ago. Nothing that makes the viewer take a certain period into account when looking at the work. Johnny could have been stuck in the mud yesterday or in 1940.

I want the characters to have their own space, without any built-in narrative or nostalgia surrounding them. 'This could have happened at any time' is what I'm going for, I guess. So to answer the question directly, I would say the relationship is seamless: the same issue that lingers over the face of a young man from the nineteenth century still plays out the same way on his great-grandson's face today.

- I'm curious about the new monograph you're working on, as well as any other new projects.

I'm quite excited about this Rizzoli publication [Hernan Bas, to be published in May]. For someone who loves books and has found such delight in so many artists' books, I am really proud to have one of my own. I think al l artists like having their works published. Early on, I found art by poring through the library, not through the museum. And I'd love to have my paintings stumbled upon again in 40 years, in some dusty spot, by a young artist who didn't know me from shit.

Apart from the monograph, I also have two forthcoming shows this spring, first in London with Victoria Miro, then Hong Kong with Lehmann Maupin. I haven't quite nailed down a story as far as what I'll be exhibiting, but as I mentioned before, I'm quite interested in nineteenth-century caricaturists at the moment, combined with a kind ling interest in turn-of-the-century decorative arts in America. I've also begun privately writing short character studies lately - they all end with the line, 'Currently, (insert name here)'s boyfriend is a psychoanalyst from New Jersey.' How this will all come together or not is still a mystery to me.