Flip-Happy Market Sees Artists Pulled Out of Retirement

By: Julie Baumgardner

By now your feed has undoubtedly been flooded with #TheArmoryShow. At many a fair these days, the hits and highlights pop out aplenty with a quick perusal of your Instagram feed. Beyond trend forecaster, the platform is a market maker too—figures that have been floating around claim that as many as 40% of art sales in some sectors of the market happen through the image-sharing service these days. Traditional gallery model beware—maybe. But this year, swipe after swipe, no clear top trends have emerged from The Armory Show’s aisles—even Jeppe Hein’s mirrored YOU ARE SPECIAL (2014) only snagged a few obvious selfies.

Walking through the booths, the same sentiment popped out—well, nothing popped out. Gone were the mega-flashes of megawatt neons. Nips and hips, too, were covered up. And there wasn’t a Koons and only one Hirst in sight. Though trends are typically determined on works’ formal properties—Glitter! Abstraction! Wall-Sized!—over the past two days what began to emerge as “trends” among the works on view fell more along the lines of the types of artists chosen by their dealers and where they stood in their careers.

Three distinct sorts became apparent: the Mid-career Museum-friendly, the Golden-Years Golden Nugget, and the Slinging Young Gun. Catchy names aside, what rang true for this year’s Armory Show refers back to what director Noah Horowitz emphasized as making the fair distinct: regional institutional presence and curious New York collectors. Horowitz also noted that The Armory Show plays an active role in the booth curation process, so perhaps we’re seeing his hand at work here, too.

So with so many trustees and curators from across America’s heartland in town, it seemed as though dealers were putting out artists who either are currently in institutional shows or will be soon. At Lehmann Maupin, that is the case for nearly everyone they showed. Take Nari Ward, whose exhibition “So-Called” is up at Savannah College of Art and Design and his “Sun Splashed” at Pérez Art Museum Miami opens October 2015. Such is the case with Do Ho Suh, who has an exhibition at MOCA Cleveland come September, or Angel Otero, who has a big solo effort at Dallas Contemporary coming up, also in September.

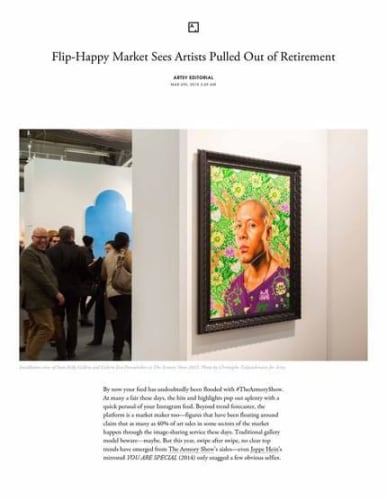

Over at Sean Kelly, the star was Kehinde Wiley; his Portrait of Natasha Zamor (2015) was one of the first works to sell in the booth (for $125,000). Lest anyone forget, Wiley’s retrospective at the Brooklyn Museum just opened a few weeks ago. Victoria Miro seemed to be counting on the same strategy—offer the artists with institutional cred—with a strong selection of paintings from Chantal Joffe and Varda Caivano. Caivano opened a solo show at the Renaissance Society in Chicago on February 22nd. Joffe will unveil a series of 20th-century women at the Jewish Museum, in New York, on May 1st.

El Anatsui brings us to the next point. Lately the market, perhaps in reaction to its youth obsession, has been gaga for artists in their second childhood. That’s right, 75 is the new 25, or 80 is the new 30, and it’s not just 71-year-old Anatsui hogging the attention. Brazilian notable Galeria Nara Roesler installed a massive, hanging yellow-plastic-planes sculpture—part gazing sun, part gilded orb—by the 86-year-old Julio Le Parc, who continues to produce prolifically.

Meanwhile over at Gallery Espace, Indian mathematical printmaker Zarina Hashmi’s miniature gold-leaf abstractions emerge from the hand of a 78-year-old—and both puzzle and delight. Then there’s Frank Stella, who is no stranger to art historical fame, but at the age of 78 is producing works that according to a director at his dealer Marianne Boesky Gallery: “We got them before Frank could say no or decide not to sell them.” Interestingly, Stella’s curvilinear stainless steel wall-mounted abstractions—a shift in style—which were asking at $275,000, a little under the auction rate for his 1980s and ’90s experimentations with sculpture, represented another bucking trend.

The expansion of an artist’s market must be done deftly. The blatantly factory-like production currently plaguing so many young artists, especially in the “bro school” and “flip art” categories, is a testament to changing times: galleries no longer have total control of their artists. However, the last trend that really stood out in my perusal of the piers were efforts to expand the markets of certain young stars on major gallery rosters.

What does that mean? For example, at Lisson Gallery, Wael Shawky created a series of drawings based off his marionette videos of an Arab perspective of the Crusades. The gallery is asking $16,000 for the works. Usually Shawky’s prices are double or almost triple that figure. Similarly, Reza Aramesh, who has long been represented by Leila Heller Gallery, has a collection of unique collages on offer for only $5,000 a pop. The buzzy Iranian often sells his photographs and collages for up to five times that amount. As the art market foists changes on the traditional gallery model, perhaps they are regarding fairs, or in particular The Armory Show, as a place to experiment with doing what Americans do best: make money.