Dark Matter

By: Pauline J. Yao

Whether slicing through refrigerators and washing machines, digging trenches in gallery floors, or erecting bristling, kaleidoscopic structures made from demolition debris, Beijing-based artist Liu Wei engages the realities of our contemporary infrastructure with a singular intensity. For him, the corporeal surplus of burgeoning consumerism and near-frantic urbanization in China and in the world at large--the junked appliances, the scraps of wood and metal--is a vehicle of rupture and disturbance, a means by which to both figure and counter the destabilizing forces of sociopolitical transformation. Here, curator and critic Pauline J. Yao looks at a practice that unlocks the renewed critical capacities of matter itself.

Visitors to Beijing are invariably astonished by the profusion of vehicles clogging the city’s roadways: bicycles, tricycles, mopeds, carts, and aluminum-clad motorcycles in all shapes and sizes, each outfitted and equipped for a highly specific purpose. It is the sheer variety, not the volume, that is the most surprising thing of all. The stereotypical impression of contemporary China may be one of conformity, as emblematized by the Mao-era sea of bicycles or Olympic-ceremony performers in lockstep, but beneath the surface lies tremendous diversity-one just has to be trained to look for it. Liu Wei’s practice could be conceptualized as a heuristic enterprise dedicated to precisely this kind of training, one made all the more necessary by the fact that heterogeneous forms of inequality regularly go unnoticed in China. It’s hard to fathom the gulf that lies between the spaces where the artist’s sculptures, paintings, and massively scaled semiabstract installations are produced-a studio compound in the semirural reaches of Beijing-and the well-heeled museums, galleries, and centers of the global art world the works have been known to occupy. Yet Liu’s attention to this gap is brought into focus every day as he commutes from his upscale residential neighborhood to the entropic settlement of Shijiacun nestled outside the fifth ring road.

Shijiacun, or “Stone Village,” is technically part of Beijing, though you wouldn’t recognize it as metropolitan from the single-level dwellings lining dusty streets. Nor is Shijiacun occupied by Beijingers in the strict sense; rather, it is populated by migrants who have ventured here from the countryside seeking work. The unresolved status of these individuals-who, according to China’s outdated household-registration system, qualify as neither urban nor rural since they are living outside their registered hometowns and lack permanent-residence permits-is emblematic of China’s swift urbanization and of the residual effects of a socialist classification system that has outlived its usefulness yet still lingers. As much as any individuals or institutions in China today, the denizens of Shijiacun embody the destabilizing and disorienting effects of the transition from an agrarian to an industrial and postindustrial economy, from Marxist dialectical materialism to materialism tout court.

Within the ranks of Chinese artists, Liu Wei has proved especially adept at revealing and probing this web of contradictions, as was evident in his solo exhibition “Trilogy” this past summer at Shanghai’s Minsheng Art Museum. His practice has been defined by a process of steady accretion-visual styles growing more layered and materials accumulating and multiplying-that reached its apotheosis here, in a frenzied surfeit. One of Liu’s most significant works, Merely a Mistake II, 2009-11, an agglomeration of polychromed wooden door frames, metal bolts, and other detritus culled from demolition sites, was prominently featured. In the work’s previous incarnation at Beijing’s Long March Space (Merely a Mistake I, 2010), Liu had created trench-like depressions in the gallery floor and installed these structures inside them, creating the effect of an archaeological dig. Here, gracing the museum’s grand hall, the pointed archways, rectilinear buttresses and spires, and faceted, dilated forms came across as futuristic yet rough-hewn incarnations of Gothic architecture. For Golden Section, 2011, the artist crudely conjoined simple, everyday furniture with the kind of ornate furnishings popular with China’s nouveaux riches, suturing the two types of objects together with unwieldy metal panels to create bizarre hybrids. A bank of old TV monitors emitted sporadically pulsing lines of static (Power, 2011) as the sets were programmed to turn on and off in a staggered rhythm, while a painting from the artist’s kinetic “Purple Air” series, 2005-11, hung on a wall. Additional paintings, these from Liu’s “Meditation” series, 2009-, struck a slightly more subdued note with thick layers of paint built up in wide horizontal bands.

The Minsheng show functioned as a culmination, illustrating a constellation of ideas that have been circulating in Liu’s practice since 2006. First and foremost, it elucidated his use and figuring of urban architecture and cast-off industrial or consumer objects-also implicitly urban. Preceding Merely a Mistake are a number of similarly sprawling “cities. ” Among the best known is Love It, Bite It, 2006-2008, an enormous model metropolis, made entirely of rawhide, that impossibly brings together St. Peter’s cathedral, the Pentagon, and other global landmarks. In 2007, Liu produced the installation Outcast, a giant ramshackle edifice that evokes a dystopian megastructure. Filled with barren trees and institutional chairs and desks arranged in circular formation, it is reminiscent of an empty meeting space-a defunct village assembly, perhaps. The “Purple Air” paintings, meanwhile, suggest skylines as much as attempts to map the immense verticality of a megalopolis’s infrastructure-the flows of water, waste, power, traffic, and information that constitute the substrates and material preconditions of urban existence.

Above all, the city Liu presents is ahistorical. It is mindless material flux, decay, demolition, and construction. China’s building boom has effaced structure after structure, flattening the built environment into an endless tabula rasa. And in a city without history, we are submitted to a completely overwhelming perpetual present. There is no historical narrative through which we can organize our experiences, only the just-past and the chaotic here and now. “Reality is so powerful,” Liu commented once, that we “feel numbed most of the time.” If works like those shown in Minsheng are any indication, he feels that this numbness is best met with a potent clash or disturbance that holds the potential to stimulate our senses and force a reexamination of how we interpret or understand the world. Yet his is not a simple return to the strategies of defamiliarization and perceptual renewal famously pursued by Western avant-gardes for the better part of the previous century. That renewal, that experience of flux and shock, is already a condition of China’s ceaseless overturning, resulting in an adamant erasure of history that hardly makes way for a utopian future. The point of Liu’s tactics is not to quixotically restore some semblance of a lost temporal or historical continuum-least of all a positivist one-but to find an artistic paradigm capable of brooking, perhaps even illuminating, the endless disturbances of the present.

Born in 1972, Liu is the first of his generation of artists to be given full command of the cavernous main halls of the Minsheng Art Museum for a solo exhibition. In light of this distinction, it seems ironic that he began his career as a member of the subversive quasi movement known as Post-Sense Sensibility. In fact, it would be next to impossible to expand on the multilayered and multimedia nature of Liu’s art without some elaboration on this equally multivalent label, which may designate a seminal exhibition of that title that took place in Beijing in 1999, a series of ensuing shows held in makeshift venues in the city from 1999 to 2003, or the associated group of artists who came together around a shared distaste for the political idealism and rational leanings of their predecessors. The Post-Sense Sensibility artists embraced irrationality, improvisation, and intuition and strove to create extreme experiences. Though frequently likened to the Viennese Actionists or the YBAS (and as with the YBAS, many of these artists, such as Sun Yuan and Peng Yu, Yang Fudong, and Qiu Zhijie, would go on to prominence), the group is most indebted to the anti-art and anti-ideology stances of Fluxus. With the exception of the namesake 1999 show, their exhibitions were premised on self-imposed rules that each artist reacted to individually on-site. This effort to carve out a self-reliant, independent model of practice, one predicated on spontaneous context-specific responses-not the Grand Guignol theatrics found in much of their work-was the key characteristic of Post-Sense Sensibility.

Liu’s own contribution to the 1999 “Post-Sense Sensibility” exhibition was the multichannel video Hard to Restrain, 1998, in which naked human figures scurry around like insects under a spotlight. It was his second attempt at video, the first having been shown just two months earlier in another underground exhibition. Three years before, he had graduated from the China Academy of Art in Hangzhou with a degree in painting and then returned to his hometown, where his painting practice quickly gave way to experiments in other media. He participated in a number of DIY exhibitions in this postgraduate period while supporting himself as an editor at Beijing Youth Daily. In 2003 was invited by Hou Hanru to participate in the Fifth Shenzhen International Public Art Exhibition, “The Fifth System: Public Art in the Age of Post-planning.” Accustomed to working in a collaborative manner with a close-knit circle of friends, the artist now had an opportunity to create a solo project with an internationally known curator in a public, “official” (read: government-sponsored) exhibition. His first proposal posed significant logistical hurdles-think procurement and transport of an airplane boarding bridge to a publicly accessible site. Though the idea was initially accepted, it never came to pass-it was too ambitious and too expensive. (Instead, he contributed three large-scale outdoor swings.) What might have been a foreseeable disappointment for many artists-especially those working in the public sphere-registered as near calamity to Liu. For the first time, he witnessed the capacity of the “system” to thwart his work and realized his own inadequacies in negotiating the budgetary and political concessions necessary to make art within that system. He cites the mishap as a turning point in the evolution of his practice from the dogmatically experimental yet ultimately starry-eyed, subjective ethos of Post-Sense Sensibility toward a more pragmatic approach.

With this contretemps behind him, he entered a new phase. It was a time in which, according to Liu, “I could no longer keep reality at a distance. I started to observe and think anew about how all things we encounter have their own histories and purpose.” By 2006, there seems to have been a decisive break: The works he would produce over the course of the rest of the decade are marked by concern with the objects that populate our daily lives and, by extension, with the systems that govern everyday existence.

Crucial to this shift was Liu’s “Anti-Matter” series, 2006, a group of sculptures in which washing machines, exhaust fans, and the like appear to have been blown apart, sliced in half, or turned inside out by some unspeakable force. Twisted sections of metal splay outward in starburst formations, and the exterior plastic skins of TVs and appliances are stripped away to reveal their wiry innards. The words PROPERTY OF L.W. are emblazoned on each work. Here the readymade fulfills its long-standing role as a vehicle for artistic response to mass production and consumerism yet at the same time sharply diverges from its origins as a declaration of insurrection against the bourgeois autonomy of art. Liu acknowledges his post-Duchampian debt with the imprinted words but transforms the trope of the artist’s signature into a mark of private ownership (rather than merely authorship), a gesture that of course has a different resonance in the Chinese context than in the West. In China-where bourgeois autonomy is now itself an overturning of a very different notion of objects, networks, and property-the readymade must always carry with it the cipher of loss or failure. The stenciled words, which he has since stamped on random chunks of concrete found on the street, literally overwrite this failed model. They seem less a statement about the conceptual artist’s “power of selection” than a hortatory comment on the slippery divide between public and private property.

In fact, to trouble the ever-shifting and razor-thin distinction between art object and commodity network is to echo the role of the state. The work thus takes aim at what Liu sees as the myth of capitalism in contemporary China: Things are bought and sold on the open market, but at the end of the day they all belong to the state. The stamp bearing his initials is representative of him but also of an indeterminate authoritative power. At the same time, the stenciling is emphatically indexical, conjuring the application of spray paint to surface and thus subtly emphasizing the materiality of the works at the expense of the conceptual operation that produces the readymade.

In another series from 2006, “As Long as I See It,” Liu used the cut to foreground this tension. For these works, he casually shot Polaroid photographs of appliances and furniture in and around his studio. He then proceeded to cut each object in a way that literalized the optical “cuts” and occlusions produced by perspective and by the images’ framing. So, for example, if the artist found that in one of his pictures the corner of a pool table had been cut off by the Polaroid’s white border, he would actually lop off said corner. The cornerless pool tables, slivered refrigerators, and bisected sofas were then displayed alongside the corresponding photos. The altered objects push Frank Stella’s literalist axiom “What you see is what you see” to the point of absurdity. The works are wry lessons about the radical contingency of knowledge, the vicissitudes of representation and its inevitable distortions.

Over and above Liu’s engagement with the readymade, then, “Anti-Matter” and “As Long as I See It” suggest a profound reinvestment in materials, a revisiting of literal experience and substance. The works demand that we acknowledge those realms of being and form that remain with us even as emergent technologies and concomitant social modes produce new, more ephemeral kinds of vision and knowledge. This groundedness is what sets the artist apart from many currently working in China. It contrasts, for example, with the practice of Ai Weiwei, who diffuses his works into ever-expanding circuits of reproduction and publicity.

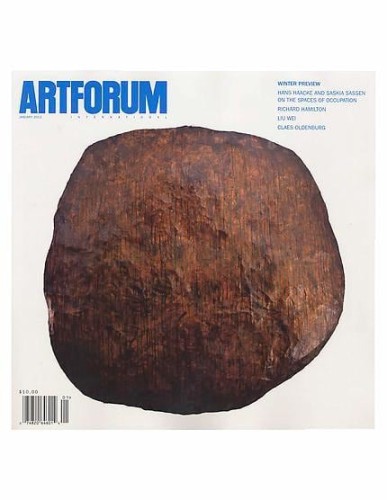

This commitment to materialism in every sense leads Liu to abstraction, a connection that was nowhere clearer than in his 2008 exhibition “Dark Matter” at the China Academy of Art in Hangzhou. It was a conventional installation in a vacant corner of a university building-sculptures on the floor, pictures on the wall-except that Liu had covered everything in black velour, transforming paintings and objects alike into abstracted masses. Outside, pitch-black monochrome velour rectangles erected on the campus grounds appeared like dark voids in the landscape. It had been only three years since he had begun painting again after his long postgraduate hiatus, and he’d initiated his return to the medium with nonrepresentational works: the “Carat” series, 2005, in which crystalline diamond shapes float on black backgrounds like oversize stars in a darkened sky. He commenced “Purple Air” around the same time. Liu pursues other painting series as well, concurrently and irregularly. These include grisaille images of waves and waterfalls done in a kind of paint-by-numbers style, and other figurative works, but one increasingly senses the primacy of austere abstractions along the lines of the “Meditation” series. Reading almost as subdued landscapes, their surfaces striped with colorful horizontal bands that suggest a computer screen on the fritz, these works emerged in 2009 as a part of the solo exhibition “Yes, That’s All!” at Beijing’s Boers-Li Gallery. That exhibition thematized the relationship between Liu’s paintings and his three-dimensional sculptural forms via explicit formal echoes: Black-and-white geometric paintings were adroitly paired with rectilinear pseudotopiary sculptures in which bands of foliage were interspersed with horizontal neon lights, while the oscillating static playing on stacked TV sets chimed with the abstract canvases as well.

Language is conspicuously absent from Liu’s practice, with the property stamp-less text than icon-almost seeming to emphasize his wariness of words. In Liu’s world, talk is cheap. He once told me he thinks most Chinese artists spend 90 percent of their time talking and only 10 percent working, while maintaining that in his own case this ratio is reversed. He pointedly avoids an online presence-another factor that sets him apart within China’s clubby art scene, which is fueled by incessant chatter via bloglike social-media sites such as Weibo (China’s answer to Twitter). Yet Liu’s notion of artistic production is not that of a Luddite-he doesn’t harbor romantic views of the heroic artist in splattered overalls. Any visitor to his studio compound will see plenty of physical labor going on, but little of it is performed by the artist. Liu began hiring nearby villagers to assist with odd jobs as early as 2006, and since then the number of helpers has multiplied. His paintings and sculptures are now wholly produced by teams of assistants and fabricators. For instance, the trees, waterfalls, and mountain landscapes of his representational paintings are digitally generated by Liu, then transferred to the canvas and deftly filled in by hand by teams of assistants. However, this automation stops short of mechanization. Liu prefers to retain the slight imperfections, anomalies, and deviations that come with a human touch. His horizontally layered paint-

ings have no digital templates but are still created by assistants, whom the artist instructs step by step. There is an element of improvisation here: Assistants lay down a stripe, and the artist looks at it and decides what to do next. Neither party knows how the end product will look. In his sculptural works, Liu cedes even more control. Installations such as Outcast and Merely a Mistake are cobbled together section by section by workers who follow the artist’s off-the-cuff verbal instructions, which are only augmented occasionally by sketches and never by technical drawings. Neither Liu nor his construction team is fixated on the final outcome.

So although Liu rarely comes into physical contact with the materials he employs, he labors as a synthesizer, facilitator, and manipulator of signs and objects. His rejection of the need for artisanal expertise, in an age of de-skilling and detached, “post-expressive” artmaking, is far from exceptional and places him in the company of numerous other Chinese artists (not only Ai but Madeln Company/Xu Zhen, Yan Lei, and Zhang Huan come to mind). But Liu’s production methods are not tied to any aspirations to undermine authenticity by churning out “product” under the aegis of a brand. He is not trying to make aft look or act more like a commodity (it already does), nor is he undertaking these methods simply to expedite completion of his designs. His installations, created without a blueprint, emerge from a process of tinkering and fiddling as workers add and insert shapes in a theatrical form of extemporization. In such works the artist’s subjectivity lies squarely in the use and manipulation of worker “stand-ins.” Ask Liu how a particular shape or form came about and he will shrug his shoulders and defer to his workers, as if he had nothing to do with any of it. What’s more, he has been known to revisit earlier “finished” works and make significant alterations to them, as if his sculptures are like any other form of matter, inhabiting impermanent states, constantly in flux. This is a reimagining of bricolage, which in its modernist incarnation presupposed a historical past, a dustbin that could be mined. Erecting his structures on the flat, unstable plain of a perpetual present, Liu gives form to a kind of antinarrative, not so much evoking history as figuring its loss.

All this should be seen in the light of the increasingly perturbing symbiosis of art and business in China. The very real ramifications of this imbrication-for instance, private museums and art centers subsisting on corporate rental exhibitions, and underfunded State-run institutions quickly following suit-raise profound questions about art’s capacities beyond the market and, most important, about what role artists can or should play within the system. In this regard, perhaps the most significant transformation brought about by the de-skilling of artistic labor in China is the shift it has engendered in the status of artistic production and thus in the artist’s role. This shift is not simply a matter of deposing the artist as genius-it constitutes a recognition of the fact that the artist has almost completely become an entrepreneur, a hack, a freelance cognitive worker. And yet within the economy of Chinese art, a nexus more totalizing than most, Liu reminds us that the most somatic forms of process and labor, however displaced, still stubbornly persist. He proposes that artists can and should engage all these spheres of productivity--of making and working, of materiality and representation. To do so is not to regress, but to complicate and deepen an emergent model of the artist’s role.

When one realizes that anyone can be an artist, it becomes imperative to think, ontologically, about what it means to be an artist at all. Indeed, the work of artists must forever be elusively, conditionally, and situationally defined, not least in China, where such categorizations are fuzzy and awareness of contemporary art among the general public is minimal at best. Not long ago I asked Liu how his assistants might describe him; that is, whether they view him as a boss, teacher, instructor, master, or something in between. It seemed natural to assume that one of the above designations would be appropriate. But when Liu’s half-joking response came back-“a capitalist”-a chasm opened up again, this time not between Shijiacun and the glitterati of the art world, but between different mind-sets that interpret his actions either as discursively pushing the boundaries of contemporary artmaking or as pragmatically embracing the entrepreneurial spirit. Neither is entirely wrong. Perhaps Liu’s mindful inhabiting of various registers of artistic production points again to the effacement of historical memory and the potential of material knowledge. But for Liu, the truth is in the making.