Rigid Compromises: Liu Wei's Art and Hard Reason

By: Philip Tinari

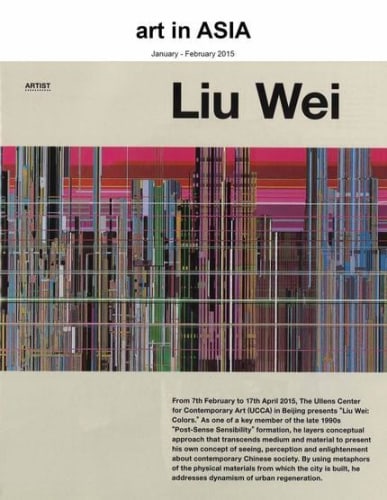

From 7th February to 17th April 2015, The Ullens Center for Contemporary Art (UCCA) in Beijing presents "Liu Wei: Colors." As one of a key member of the late 1990s "Post-Sense Sensibility" formation, he layers conceptual approach that transcends medium and material to present his own concept of seeing, perception and enlightenment about contemporary Chinese society. By using metaphors of the physical materials from which the city is built, he addresses dynamism of urban regeneration.

September 2004. Another Shanghai Biennale is about to open in a city and a country that has conceded the pleasures of contemporary art, and Liu Wei has proposed for it the work that would announce his emergence - if only it had it been approved and realized. There, in the plaza outside the Shanghai Art Museum building Liu Wei wished to install a train car, rotating axially on a giant turntable, identical to the ones that are used to move train cars from track of one gauge to another when they cross the border between one systern and another. It was to be a freight car, not a passenger car. And inside the container atop the chassis was to be hidden an entire miniature exhibition thus "smuggled" into the official biennale.

Liu Wei's train car would have complemented another outdoor work by his Shanghai friend and collaborator Xu Zhen, in which the clock atop the museum's tower was sped up such that the hour passed in seconds for the duration of the exhibition. These two modalities - the ineffable sense of being stuck spinning in limbo between systems, and the sense of living amidst construction at a frenetic tempo- were, at that moment, basic to the act of living in a Chinese city. If Xu Zhen' quickened clock was a visual pun on the acuteness of the urbanization then going on, Liu Wei's rail-gauge converter was a somewhat more complex exploration of how things on the ground work under such heightened conditions, juxtaposing the indeterminacy of the present (as materialized in the rotating plate) with the possibility of social and political action still allowed by this transitional state (as exemplified by the contraband inside the container).

Post-Sense Group and Emerge as the New Star

When the turntable proposal was denied by the Biennale organizers at the last minute, Liu Wei was forced to compromise. Instead of changing the scale or direction of his original proposal, he abandoned it completely, shifting strategies to serve up a witty indictment of traditional Chinese aesthetics (and Western fantasies of those aesthetics) in the form of a black-and-white photograph titled Looks Like a Landscape. In this work, what looked like a landscape were in fact the upturned buttocks of a group of models, gluteals thrust into the air to form a mountainous scene evocative of the quintessentially Chinese vista from a karst-peak river cruise in the southwestern tourist town of Yangshuo. It is a piece less ambitious, but almost more subversive than the one originally proposed- and made all the more so by the eagerness of Western collectors to embrace its statement, best exemplified by Uli Sigg's decision to use it as the inner leaf for his Mahjong catalogue the following summer. And so even though his train would go unrealized, the photograph that Liu Wei himself "smuggled" into the 2004 Shanghai Biennale would still prove to be a switch between metaphorical rail gauges for the artist himself.

The train-car piece rested on the idea of a conversion of between systems - a technical adjustment that happens at a single moment- as a metaphor for the individual's response to historical and ideological transformations taking place over time. This moment of conversion is itself a moment of violence, a recognition of the basic structures that govern the world, often without our awareness. Qiu Zhijie, the intellectual leader of the Post-Sense Sensibility group of artists with whom Liu Wei first came to international attention in 1999, even wrote of an incident involving a video work by Liu Wei and the violence of technical standards in his famous essay "The Important Thing is not the Meat." Qiu recalls a lecture he delivered at Harvard's Fairbank Center in 2001, where an undergraduate asked him why Chinese art was so violent. Qiu replied by pointing to the VCR, which could only play a Chinese cassette in the "PAL'' format in black and white, while an American cassette in the “NTSC" format could play in color on any VCR worldwide. Concluded Qiu, "And thus Liu Wei's strikingly colorful work has been completely lost! What is viol nee? In my mind, this is violence, the violence of American imperial arrogance!"

If in 2001 it was only possible to decry these uneven power dynamics, by 2004 Liu Wei sensed that he could author his own conversion narrative. And so the incident surrounding the train car piece became a moment to shift from the underground practice of the Post-Sense Sensibility crowd into the light of a global art system newly looking for a few good Chinese. It was a good moment to concede the necessity of a consolidating a market position: the very first round of dedicated Chinese contemporary was just about to happen in Hong Kong, and the acquisitive frenzy among both Western and Chinese collectors which has ensued had not yet begun. It was clear to anyone paying attention that contemporary Chinese art had moved from a state of "sensation" through a process of "legitimization," and that the price of the new freedoms allowed by a more open climate and the material comforts brought on by a more avid market was going to be the collapse of the theoretical grounding for the avant-garde work in which the Post-Sense group had been involved. "When that object of opposition is gone," Liu Wei recalls, "things become much more difficult to sustain."

After the success of his landscape photograph, Liu Wei began making other landscapes, monochromatic scenes he sketched on his computer and then had his untrained assistants make into acrylic-on-canvas paintings. Paintings sell, after all, and for Liu Wei now as for Deng Xiaoping in the 1980s, money had become "hard reason." It was a prescient, and extremely successful, strategy as he went in less than two years from apartment to villa, Cherokee to BMW, cramped second-floor studio to sprawling courtyard studio. That these happened to be the two years during which Chinese art has come into its own as a market category almost seems secondary, and somehow unlike the countless other Chinese artists who have made their fortunes during this period, his seems to have a conceptual integrity about it.

He rarely appears in the auction catalogues, but is a staple of the right kinds of art fair ; the people moving his work have not wholesaled it to low-end, Chinas pecific dealers in New York and Paris (as was the case with so many of the auction-star painters of the 1980s generation) but carefully placed it in respectable collections, Western and Chinese. At a moment when artistic reputation-making is essentially a process of branding and marketing, and in a context where few have figured out how to play anything but the most vulgar sort of "China card," perhaps Liu Wei's strategy has a legitimate claim to make as an artistic position. And if his paintings offer an easy source of currency, both financial and symbolic, they also endow his practice with a foundation on which he continues experiments more in the vein of the unrealized train car. His sculptures and installations moved through a transitional phase in 2005 largely grounded in visual one-liners—paintings that looked like animal skins or glimmered like diamonds and galaxies, sculptures in the shape of giant turds through which poked the plastic detritus of China's consumer society, assemblages of mass-produced cups and dishes evocative of rockets and missiles, giant panels of camouflage composed of tiny pandas emblazoned "PROPERTY OF L.W."- to works reflecting a subtler set of concerns about subjectivity, and ultimately citizenship.

Criticism on Chinese Contemporary Society

In 2006 and 2007 he has realized a long string of works that revolve around the theme of exteriority. This body of work began with a set of sculptures resembling parliament buildings from capitals around the world, crafted from the oxhide generally used for making doggie treats. (Liu Wei's original concept was to unleash hungry dogs upon the sculptures, but when the "36 Solo Exhibitions" project in Shanghai in which they were to be shown in May 2006 was shut down, the work morphed into a more permanent presentation.) The sculptures are not flattering renderings of the buildings they present, and moreover, they are grouped together in cramped conditions, forming a veritable ghetto made from seats of political power. Standing less than knee-high, the intricate yellow-brown architecture set up an interest in the projection of power that has expanded in later works.

For a solo exhibition in late 2006 at Beijing Commune, Liu Wei paired Polaroid photographs of everyday objects with the actual object themselves, cut such that the objects existed in real life precisely as they did in the images. If a corner was cut-off in the photo, so too was it cropped, using a powerful saw, from the object. For Liu Wei, this cutting marked an assertion of the artist's power. As he has said, in these works, 'You can only see what I allow you to see. You cannot see what is out of the frame, but the whole thing is mine." And yet it was also a sarcastic gesture, a concession that the artist in this particular context has only the power to cut what he can buy- a couch, a rod, a table. "Don't even think of trying to do anything more, there's absolutely no possibility," he says. In cutting, Liu Wei at once projects his power as an artist and mocks its humble limits. And in doing so he sets up a homology between what is visible in the physical, visual, artistic sense, and what is visible in the political or social sense. It is a critique so radical that it slips unnoticed into the conversation.

His next major installation, realized in April 2007 for ”NoNo" a group show of the remnants of the Post-Sense Sensibility crowd and its Shanghai peers at Beijing's Long March Space- was even more direct. In it, Liu Wei placed a set of brightly colored exercise equipment, identical to that on which senior citizens do their daily calisthenics in middle-class residential compounds all around China, inside a giant cage. These exercise machines, which suddenly proliferated around the country after the Falun Gong scare of 1999, are an apt symbol of the way in which the socialist state attempts to provide minor comforts to its aging faithful, albeit with ulterior motives of keeping them away from unpalatable movements, even as bigger problems of their health care and pensions go unresolved. Explained in this way, the work sounds almost too direct, positioning (Chinese) subjects as encaged animal, left by a totalitarian government to run on their hamster wheels. But the materiality of the work stifles such a simple reading: put before the viewer, this composition appears almost architectural, the sharp verticals and rigid corners of the rust-colored iron cage playing off the rounded edges and happy blues and oranges of the machinery. Add to that a few sandwiches and pieces of fruit scattered around the floor, almost as if to suggest a band of feral animals had gone been inside and would soon return, and the work takes on an entirely different kind of ambiguity.

It became clear at this point that Liu Wei's interest no longer lay simply in consolidating a base of power from which to face the global market and curatorial system, but in actually articulating a subject position for the individual in the face of the current Chinese order a task of overwhelming complexity that he has only just begun. The vague sense that the people who use machines like the ones in this sculpture are subject to negotiations and compromises beyond their control, or even their imaginings, gained a fuller presentation in another solo show titled The Outcast that opened the following month, at Universal Studios-beijing in May 2007. For this exhibition, Liu Wei constructed an airtight structure out of doors and windows culled from generically governmental buildings- think musty glass and that pea-green color with which the lower portions of walls in Chinese schools and hospitals are painted. Inside he placed an assemblage of old furniture which suggested a meeting room, leaving the viewer perpetually on the exterior of the imaginary deliberations happening within.

Giant fans positioned at each of the structure's four corners blew dust and papers into a perpetual flurry. Smaller sculptures and paintings surrounded the structure, including an eternally dangling phone receiver, a collection of police lights set in black boxes, a rigidly perspectival painting of a long, bureaucratic corridor. This idea of the "outcast" for Liu Wei does is not about the fabrication of a rebellious artistic persona, but rather about the most meaningful form of political engagement he can envision given China's unique situation. In the "Outcast" works, as in the oxhide sculpture, he presents architectural exteriors. Standing among such works, Liu Wei asks us to think of how "What happens on the inside has absolutely connection with you. Sure they it to do with your society, but the real action has nothing to do with you personally. All you have is this emotional state. If you're lucky, you have the slightest bit of your own viewpoint, your own faculty of judgment, your own ideas. But of course you are still on the periphery. If you had no idea at all, then you don't even count as an outcast if you are just part of society." The articulation of this "outcast" position is an attempt to answer no less a question than what it means to be a citizen of the People's Republic of China at the cusp of 2008. It is a question at which Liu Wei has arrived through a long string of negotiations, even compromises, with the orders that structure his own existence and sphere of action- orders he admits he cannot even always fully see. And yet at the intersection of a firm critical consciousness and a constantly shifting palette of strategies and devices, he has come upon a way of working that we might call rigid compromise, making the best of the hand dealt by turning its terms into his terms.” "There's nothing bad," he has said, "about confusing yourself. Anything can be started over, anything can begin again."