It's a long way up the side of Bukhan Mountain to Lee Bul's studio, on the northern outskirts of Seoul. It's not the tallest mountain in the area, more of a hill, but it rises steeply above the city, overlooking the presidential palace at its base. The air is crisp and clear here, and three huskies jump out of the yard into the driveway as my car pulls up to a humble two-story house with a gray cement brutalist facade. The 44-year-old Lee, best known for her porcelain cyborgs and silicone monsters, lives here with her husband, James. It seems far too small to hold a studio that can accommodate her grand designs and high-tech inventions.Yet on the ground floor, in two adjoining rooms that serve as an office, Lee maintains her "think tank," where she designs, plans and fabricates most of her sci-fi-inspired sculptures.

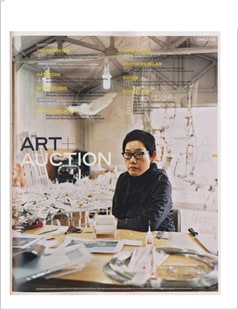

Diminutive yet self-assured, she is the antithesis of a diva, dressed in a sweater and trousers in muted grays, her eyes owl-like behind thick-rimmed glasses that mask her gentle expression. Occasionally, her husband, a Korean American writer and critic, steps in to help with translation. Through it all she maintains a

sense of humor, laughing when words fail.

Lee first came to international attention in the late 1990s for

her "monsters": half machine, half Venus de Milo meditations on

the female form of the future. She also created "karaoke pods,"

gleaming capsules in which visitors could sit and sing written-out

lyrics to piped-in music with no audience or outside interference.

These early works explored the body, both representing it

and using it as a metaphor for the fallibility of technology. Their

striking power led to Lee's being included in major exhibitions

worldwide, from "Au-deJadu spectacle," at the Centre Pompidou in

2000, to "Global Feminisms," at the Brooklyn Museum in 2007.

Although she uses a freestanding shed for larger pieces and rents a warehouse space in downtown Seoul, it's in the quiet

of her mountaintop house that Lee conceives her ideas about the collision of beauty and technology. It's also here that she, with a handful of assistants, develops these ideas into material forms that look as if they'd been produced in a special-effects studio.

The house offers spectacular views of the city below, a

panorama reminiscent of Blade Runner, especially at night, when

Seoul turns on its neon lights. It is easy to see the influence of this

landscape in Lee's latest series, "Mon grand recit" ("My Great

Tale"), begun in 2005 and featured in her show this past winter

at the Cartier Foundation in Paris. That exhibition included

12 pieces: six of them combinations of crystals and metal chains

on metal armatures that hung like surreal chandeliers, and six

resin sculptures stationed on the floor, like mammoth molten

rock formations, reflecting the gleaming surfaces of the light-filled

Jean Nouvel architecture. These works, simultaneously

delicate and imposing, were inspired by the utopian plans of

20th-century visionary artists and architects and were presented

as fragile ruins of a long-gone modernity.

When I visited her studio, that exhibition was still on, but Lee

was already planning her next New York solo gallery show, which

opened May 8 and runs through June 14 at Lehmann Maupin. It features two works from the Cartier exhibit- Bunker (M. Bakhtin), a huge black fiberglass boulder that visitors can enter, and a piece from Lee's "After Bruno Taut" series, a sort of inverted chandelier with a

filigree of chains and crystals-as well as three new sculptures from the "Infinity" series, diorama-like landscapes embedded in mirrored vitrines. Her office had pen-and-ink drawings pinned to its walls and Styrofoam models on every ledge, including a miniatute of Bunker in foamy blue and an Erector Set version of one of her largest works, Aubade, an aluminum structute with LED lights that rose more than 13 feet at the Cartier Foundation.

"I don't know when I started," Lee admits when asked

how long it took to prepare for her cutrent shows. Her creative

process involves extensive reading and research, blueprints and

model making before she even decides to begin on a work. "I start

to sketch or just write about my ideas and put them up all over

my wall in my studio, and evety day I watch this grow into a

map of ideas until one day I think, 'Maybe I can make this

more concrete and specific,' " she says.

"Mon grand recit" is something of a departute for

Lee, comprising otherworldly landscapes based on failed or

unrealized 20th-century utopias that she studied. She first took

up this idea in 2005, during a residency in New Zealand in which she became fascinated by that country's history and quirky mythology. Since then she has also drawn inspiration from a wide range of modernist projects, including the Russian Constructivist Vladimir Tatlin's unexecuted tower, Monument to the Third International, and Alpine Architektur, the German architect Bruno Taut's plans, designed duting World War I, for glittering cities in a world at peace.

Lee's projects have always been built on a foundation of

theoretical writing. Her bookshelf is lined with English and Korean

texts on utopias, notably Italo Calvino's Invisible Cities, with

its magical accounts of fictional lands. Lee recalls her confusion

when she participated once in a panel discussion and an audience

member asked how she knew so much about Western culture.

She replied, "I never knew this was only yours." Lee now explains

it this way: "I grew up studying this field, so I never think about

this as 'Western' history or 'Western' cultute."

Lee is mainly self-taught in these matters, having gotten

her only degree, a BFA in sculptute, from the highly conservative

Hongik University, in Seoul. She was born in 1964 in a remote

village where her dissident parents were hiding from the South

Korean military government. The prejudice against her parents

influenced both her career choice and her career path: Art school

was one of the few options available to a child of dissidents, and her slow acceptance in the Korean art world was partially due to the insecure position of her parents in the country's society.

After graduating from Hongik, in 1987, she circumvented South Korea's stubbornly conventional art world by creating public performance

art, producing fantastic costumes with multiple protruding limbs

and wearing them into arenas such as the airport and downtown

shopping districts. These controversial works gained her international

recognition. In 1997 Barbara London, a curator at New

York's Museum of Modern Art, invited her to create a project

space there. Lee submitted Majestic Splendor, a towering vitrine

filled with funereal lilies and sequin-covered dead fish. The walls

of the gallery were lined with more fish, perfumed and vacuum-packed

in plastic bags. The stench that nonetheless resulted was

part of the point of the piece, highlighting our unease with nature's

messier side, and the work was removed after only a few days

because of complaints from the museum staff.

In 1998, Lee was a finalist for the Guggenheim Museum's

prestigious Hugo Boss prize, and a year later she received an

honorable mention for Majestic Splendor when it was included in Harald Szeemann's "Aperto" exhibition for young artists at the 48th Venice Biennale. She was also one of two artists shown in the Korean pavilion

at that Biennale. By then, Lee was well-known for pieces suchas Cyborg- Red,1997, and Cyborg-Blue, 1997, silicone casts of archetypal female

figures from classical art reconstructed with machinelike parts. These sculptures were often interpreted as feminist critiques

of face and body enhancements. "Once they started to call my work these things, nobody tried to look at it another way," Lee says. With her karaoke pods, featured at Venice and in her 2002 solo show at the New Museum, the public came to understand that her artistic concerns are more universal, including how everyone interacts with technology.

For Lee, the overriding theme that connects these earlier

works with her more recent landscapes is the issue of perfectibility:

the human craving to create or pursue an ideal that often fails or,

worse, produces monstrous results-cosmetic surgery, industrialization

or fascist governments. "My work has always been a

representation of a desire to transcend limitations," she explains.

"So the transition has been to move from the body to the broader

idea of social structures."

When asked if her concept of unsuccessful utopias is rooted

in the recent history of South Korea or, more pointedly, the model of Communist North Korea, only 35 miles away, Lee responds that although Korean history may appear to be different from the West's in its details, the challenges of globalization and technology

are essentially the same everywhere. But one piece in the Cartier Foundation show, Heaven and Earth, does refer specifically to the famous volcanic lake atop Mount Beakdu, on the North Korean-Chinese border, a site South Koreans aren't allowed to visit. Lee presents it as a gleaming bathtub ringed by mountain peaks and filled with a noxious black fluid that gives off a foul smell.

''Lee Bul's work is like a dream being transformed from one reality into something else. We don't know whether it belongs to a world of today or a world of tomorrow," says the artist's American dealer, Rachel Lehmann, of Lehmann Maupin (Lee is represented by Thaddeus Ropac in Paris and PKM Gallery in Seoul). Despite the fact that, according to Lehmann, there is a long waiting list for Lee's pieces, prices

remain fairly reasonable for an artist of her stature, from $20,000 to $90,000 for works in her current solo show. "Collectors connect emotionally with this work," says the dealer. "They see an individual language, they see an original beauty, but they also see the quality of the craftsmanship, and they are moved."

Lee's manual methods might be surprising, given the high-tech gloss of so much of her art. Her female cyborgs look as if they were produced with CAD software, which generates three-dimensional forms. But there is no computer in her office. Instead, Lee works out most of the shapes by hand before sending the molds to a fabricator to produce the synthetic limbs in silicone or porcelain. Her approach

to the utopian landscapes is even more hands-on. For the monumental inverted chandelier of AfterBruno Taut, she and five assistants assembled the complex metal frame and then applied thousands of lengths of chain and crystals. Only the most daunting works, such as the life-size resin Bunker, are made outside the studio.

The detailed handiworkis most evident in the pieces of"Mon grand recit," such as Sternbau No. 5: a small mobile draped with hundreds of tiny chains and ropes of crystals that was featured in the Lehmann Maupin booth at New York's Armory Show in March. In Lee's studio there's a small worktable where spools of chains are arranged by size and hue. Another artist might outsource such labor-intensive production, but Lee finds that she must supervise every step of a work's evolution

and is unsatisfied with results reached in a more routine fashion.

For her, scientific and philosophical inquiry must be joined to painstaking

techniques in a way that harks back to some of art's greatest achievements. "I remember when I was six or seven years old," she says, "I read a book about Leonardo da Vinci, and I thought that to be an artist would be like that, to challenge everything and make it look great."